On July 8, the record company Croatia Records released a luxurious vinyl reissue of the album “Večeras vas zabavljaju muzičari koji piju” by the group Riblja čorba, the only such album left from “Jugoton”. Thirty-eight years have passed since the original release, and it seems like it was yesterday. Just as Siniša Škarica, the author of the rich accompanying booklet and long-time editor of Croatia Records, remembers every moment from that story, so do I. We all followed Riblja čorba closely. They were a great band. In Yugoslavia, they were perhaps the greatest band after Bijelo dugme.

The band we needed

Riblja čorba has come a long way in a short time. Their story is pretty much Hollywood-like. They got together in August 1978 – Bora Đorđević sang, Rajko Kojić played solo guitar, Miša Aleksić played bass, and Vicko Milatović played drums. During the fall, Momčilo Bajagić Bajaga joined them as rhythm guitarist. Only a few months after their founding, they already had a Yugoslav hit: “Lutka sa naslovne strane” (eng. The Front Page Doll). After the second single “Rokenrol za kućni savet” (eng. Rock and Roll for Home Council) (1979), it was possible to foresee that their hard rock would move in two directions: one where they would affirm rock and roll means fun, energy and, after all, represents a way of life, and the other where Bora, as the frontman, would play the role of a bitter, deceived and hurt man. With the album “Kost u grlu” (eng. Bone in the Throat), Čorba introduced the urban half-world to rock at the same time as Prljavo kazalište and at least a year before Johnny did. Čorba achieved and maintained its status right at the time of the apparent dominance of the new wave, which was an excellent example that the scene was already big enough and no one bothered anyone. After all, if they hadn’t stubbornly insisted on blues, Riblja čorba could have been a new wave. But we were missing just such a band. A band that would not only sing about the happy children of socialism, a band that would be firm, but would include the best elements of pop, a band that would bring new emotion to ballads and elevate them above the pathos of the song “Jedina moja” (eng. My Only One), and a band that would move the target group towards those who were still waiting for their chance knowing that they would never get one.

A raw, honest and catchy sound

At that time, it was not yet possible to know exactly what a song that would “remain”, defy time and forever be attached to the soul would look like. Today we know that only emotion remains after everything, and that only songs with strong, specific emotion stay with us. What was important for Riblja čorba’s career was that “Ostani đubre do kraja” (eng. Stay Garbage until the End) not only matched “Lutka sa naslovne strane” in terms of emotional strength, but also surpassed it. No other song from that record remained in the top ten. The sound was raw, honest and catchy. Rock went out into basements, cafes and further towards the periphery, exactly where Bora liked to hang out. It was obvious that a great poet had arrived. And what else was left for a great poet to do but to fight against injustice. Thus, Bora became a bit of Don Quixote, a bit of Robin Hood, a bit of Calimero. Still, anyone who wanted to could see it: if Riblja čorba maintained the level they set for themselves with their first songs, they could fly high.

We will never know if it would have been better for them had they continued at full speed immediately or if it was good that they went to the army for a year. Because when they swept the audience with the 1981 album “Pokvarena mašta i prljave strasti” (eng. Corrupt Imagination and Dirty Passions), it seemed that everything was going too fast. From the largest military dormitories to the largest halls in Yugoslavia, overnight. They were all still young people, just scampered out of their parents’ laps (or not even out yet), raised in the socialist middle class, completely unaware of what they were getting themselves into. However, it was nice, who could refuse that. “Pokvarena mašta i prljave strasti” turned out to be a good album, worthy of all praise. The song “Dva dinara, druže” (eng. Two Dinars, My Friend) not only reached the popularity of the song “Ostani đubre do kraja”, but surpassed it significantly. “Ostaću slobodan” (eng. I Will Remain Free) proved to be a strong message. “Joke songs” also started to appear; there was also one for the soldiers. Whoever doubted how Bora would harmonize his two sensibilities was wrong: “Dva dinara, druže”, one of the biggest hits of Yugoslav rock music in general, is pure “acoustics”. This is maybe our first rock song that ended up playing in kafanas (type of local bistro or tavern which primarily serves alcoholic beverages and coffee). That song could be read in any place where something was being played. There are not many such songs in Yugoslav rock music. I don’t know if Bora was aware of the scope of that song; it is hard to see some things right away. But his ambitions had certainly grown. He didn’t want to reach his own levels, he wanted to raise them even further.

More and more emotion, even bigger halls

Perhaps, precisely because of his ambitions, he rushed too quickly into “Mrtva priroda” (eng. Still Life) in the same year, 1981. But it’s human – let’s see how far we can reach. We did not get the continuation of “Dva dinara, druže”, but everything else was better than it was before, listeners could find their songs more easily, the range of emotions expanded. The halls where they played were only getting bigger, but they did not earn more money. Miša Aleksić was telling the truth when he wrote that his mother-in-law paid for the vacation for him and Jasna, after the triumphant tour of the album “Mrtva priroda”. And Bajaga struggled to decide whether to go with them. There was not much use for the vinyl either: first, inflation ate up a third of the money, and then progressive taxes arose. In fact, financially, they fared best where there was not that much money – in Banat. Managers lied to them that a bigger hall only produced bigger losses. This led to some quiet dissatisfaction, which began to erode the essence of everything, regardless of the fact that they were young and that gigs were still more important to them than money. Moreover, they held the Yugoslav record for most sales of an album, because until then even Bijelo dugme had not sold half a million copies, as many as “Mrtva priroda” had.

However, Riblja čorba was talked about and written about in various contexts, among others, when a girl died at their concert in Zagreb in 1982, and when NOB (People’s Liberation) fighters jumped to protest because of the verse “za ideale ginu budale” (eng. fools die for their ideals). There was too much of Riblja čorba, both where it should and where it shouldn’t.

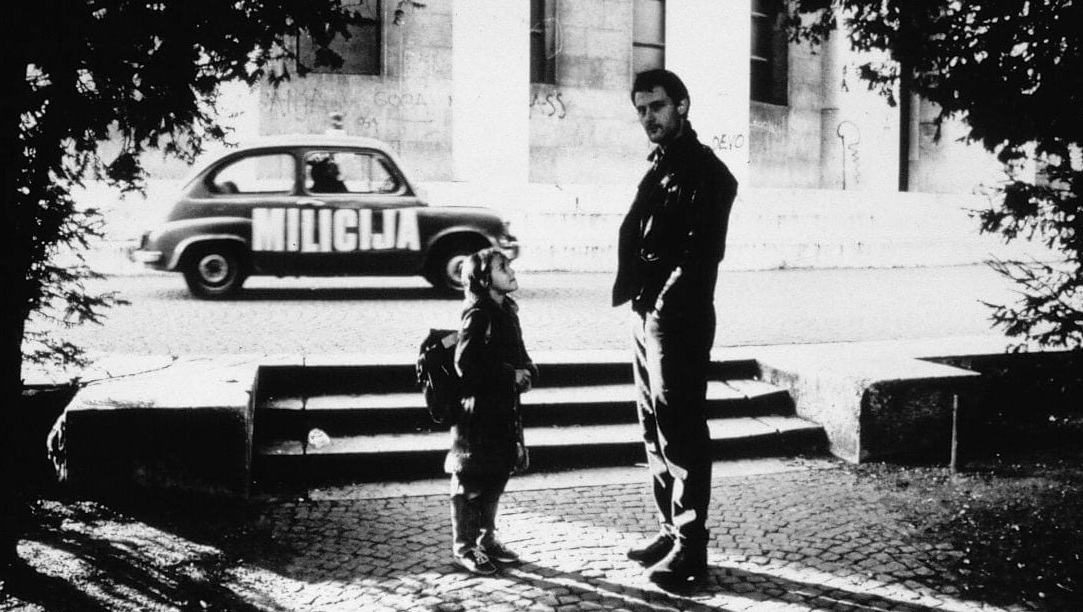

A vinyl about Belgrade at the time

Maybe they rushed into “Buvlja pijaca” (eng. Flea Market) (1982) too quickly, but they didn’t have anyone to advise them, or they did, but Bora’s ambitions kept growing. He liked the idea of being forbidden, he thought it would be good for his resume. That’s why “Buvlja pijaca” turned out to be a real record of Riblja čorba. First of all, there are strong messages against the system: “Slušaj, sine, obriši sline” (eng. Listen, Son, Wipe Away Your Snot) and “Kako je lepo biti glup” (eng. How Nice It Is to Be Stupid). The fact that Bora’s song against the influence of the NOB fighters was a success proves that the socialism of that time cannot really be said to have been rigid. Both Bora and Johnny set out at the same time to investigate the regime’s tolerance and were successful in doing so. “Ja ratujem sam” (eng. I Fight Alone) is another song that is quite effective for Čorba’s target group. However, the main ballad “Dobro jutro” (eng. Good Morning), although beautiful, could not be identified with the emotion that the audience was used to. Nevertheless, “Buvlja pijaca” is a genuine Belgrade record of the time, it says a lot about Belgrade. It was sold in nearly three hundred thousand copies. That was Čorba’s audience. Almost half a million copies of the album “Mrtva priroda” were sold due to affairs.

Transfer to Jugoton

Bora, however, was not satisfied. He was sure that PGP Records could have done better, that’s why he went to Jugoton. Bora is intuitive and knew that Čorba needed some change. In fact, at that moment Čorba needed a break. Firstly, they needed to sort out the relations among themselves. Everyone needed to make up their minds, because they were all stars individually; everyone on the tour had posters with only their image. Vices multiplied in the band. Vicko, who was one of the pillars of the band as far as stability is concerned, was in the army. Rajko brought in Vlada Golubović to replace Vicko. Vlada was probably the best drummer in Belgrade, but also a man who interfered both when it was necessary and when it was not. Bora did not like him because they were together in the band Suncokret when Vlaja refused to play “Lutka sa naslovne strane”. Rajko, on the other hand, did not like the fact that Bora’s wife Gaga travelled with them on tours. His controversial maxi-single “Ne budi me bez razloga” (eng. Don’t Wake Me up without Reason) (1983) was a kind of protest against the parent band, although these were songs that Čorba could also play at concerts. Bajaga’s album “Pozitivna geografija” (eng. Positive Geography), released in early 1984, was, however, clearly different. At the festival in Opatija, at the beginning of March, when Jugoton promoted “Muzičari” (eng. Musicians), Bajaga was constantly photographed with his record.

At that time, Riblja čorba was entering its sixth year of existence. The generational cycle of an audience lasts four to five years. Then a new audience comes, and the old one gradually thins out. New audience wants new bands. If an old band wants to get a new audience, they have to win them over with a new album, and the old ones count for something only after that. It was necessary for them to sit down and seriously think about new songs – to carefully locate and arrange the emotion in which the new audience would find itself easier. In such moments, Bijelo dugme and Parni valjak adapted through the new wave. Riblja čorba didn’t think about it. Maybe they had no one to advise them. Even Škarica, who was the editor, did not notice it when they first presented him with the songs. Maybe they got a little cocky. It happens when you believe that the audience will swallow anything you publish.

“Black” instead of new wave

If Riblja čorba did not want to go into the new wave, it entered the “black wave” with the album “Večeras vas zabavljaju muzičari koji piju”. The album turned out to be unusually dark. Bora was in a bad phase. Those of us who knew him personally got the impression that in the songs “Džukele će me dokusuriti” (eng. Mutts Will Finish Me Off), “Minut ćutanja” (eng. A Minute of Silence) and “Ravnodušan prema plaču” (eng. Indifferent towards Crying) he dealt with his environment – which may have included the band to some extent. The audience found it hard to connect with “joke songs”: “Muzičari koji piju”, “Priča o Žiki Živcu” (eng. The Story of Žika “the Nerve), “Kazablanka” (eng. Casablanca). At the time, no one cared about the film from 1943. Criminals were not as popular as they are today. The song “Mangupi vam kvare dete” (eng. Rascals Spoil Your Kids) should have gone all the way regarding the message it sends, because drugs have largely replaced alcohol miniatures. The song “Besni psi” (eng. Raging Dogs) did not reveal anything. In the end, Bora admitted defeat in the song “Gluposti” (eng. Nonsense). You can’t tell a Riblja čorba fan that you’ve given up.

The biggest hit from this album was the ballad “Kad hodaš” (eng. When You’re Walking), timelessly beautiful, the only bright song on the album and Bajaga’s “pièce de résistance”, with an unusual guitar solo by Rajko Kojić, which Đorđe Matić rightly calls “a hymn to life”. It is very likely that this song contributed the most to the album eventually reaching a hundred thousand sold records and cassettes. But it was not the emotion expected by Riblja čorba fans. It was not the identity of Riblja čorba, but a song for the fans of the future band Bajaga i instruktori. Bora became a disappointed man, and the song “Kad hodaš” was sung by a man in love. The emotion of Riblja čorba moved into the unknown. This was the album of a band having an identity crisis. The Rolling Stones also had such crises, so what.

An epitaph to his own band

The whole album “Večeras vas zabavljaju muzičari koji piju” turned out to be some kind of epitaph to the original line-up. The tour was not well-prepared and started too early. There was not enough audience and, therefore, some concerts were cancelled. After the cancellation of the tour, the band went on vacation, so the resolution of this drama had to wait for another month. It ended the way it was best, with the dismissal of Bajaga and Rajko Kojić. Bora got the opportunity to make a new, “spicy” Riblja čorba for new generations. Of course, he used that opportunity with the next album “Istina” (eng. Truth), once again by PGP-RTB Records, but the real, triumphant return will only happen with the album “Ujed za dušu” (eng. Soul Bite). It’s not hard to guess why: that’s where “Kada pade noć (upomoć)” (eng. When Night Falls) happened, one of those Riblja čorba songs by which the band is most often remembered. There is something in the attitude, the message, the image, the language, and even the arrangement, but without the song, all that is worth nothing.

On the Riblja čorba album “Večeras vas zabavljaju muzičari koji piju” there are three great songs of Yugoslav rock and roll: “Ravnodušan prema plaču”, “Gluposti” and “Kad hodaš”. That is the greatest value of this album. I hear that “Kad hodaš” is playing on the radio in Croatia once again. That’s great news.

Translation from Croatian: Ivana Bojkić