It is forty years since the double album Filigranski pločnici by the band Azra. It would be the perfect occasion for a deluxe vinyl reissue, such as Croatia Records has been releasing of late, but that isn’t going to happen. Johnny does not allow his records to be reissued. Either way, it is a good reason to remember him.

Branimir Štulić, better known as Johnny, is an extremely important figure in Yugoslav culture, not only of the 1980s and not only in the milieu where he was active. He is the New Wave’s most famous figure and the most important hero of our most important music. It isn’t Darko Rundek, Jasenko Houra, Jura Stublić, Srđan Šaper, Vlada Divljan or even Milan Mladenović, although he is the only one on a par with Johnny. If we are looking for one name, it is Johnny.

At the head of the movement of honest people

Why did we love him? Because he looked like someone who was true. He looked like someone without lies. At the time when he became a hero, there was no lie in him. He always told what he saw as the truth, no matter how bitter or painful, fair or unfair, imagined or real. Few are the people without a trace of hypocrisy in them. He could scan a person and recognize a lie in a second. He was also obsessed with the horoscope, which was rare at the time, especially for men.

He left the impression of an incorruptible person. Someone from the audience, who would take a 20-euro bribe in real life, loves Johnny because they want to know someone who is honest – because they themselves aren’t. Thanks to Štulić and then Milan Mladenović and Vlada Divljan, the New Wave came to be known as the movement of honest people.

The idol of ordinary people that want to change the world

Johnny influenced everyone, both those who wrote lyrics for songs and those who were or wanted to be (just?) poets. His language was interesting and fluent. He expanded the vocabulary of Yugoslav rock music and pushed it towards politicized art. He was as comprehensible as he should have been and maybe a little too incomprehensible than he should have been. He forever changed the poetics of rock music in Yugoslavia. His heroes spoke in words that couldn’t be heard in popular music until then. His images were powerful, often dramatic and sometimes enough for a small film. It is a shame his exciting images were never coupled with an equally exciting video production.

On the other hand, the scene enjoyed another phallocratic figure, similar to the Bosnian Bregović, only not from Bosnian forests but from the Zagreb suburbs. Bregović brought rock from the cities to the villages, but Johnny was the first to effectively bring rock to bars in the suburbs and be on a par with Mišo Kovač. He immediately became the idol of ordinary people of modest ambitions because no one had sung about them before, and with a hard sound that appealed to tough guys. At the same time, he attracted those that felt so strong that they wanted to change the world. All of these listened to this same Johnny.

It isn’t easy defining the social group he captivated. Among men, they were certainly people with inclinations toward male authority, although, at the same time, they were ready to mock such authority. Women love his tender songs. However, women fighters for human rights would never play one of his songs at their parties. Some smart people found him boring, and other smart people found him fun. Some didn’t take him seriously. Some smart people even considered him a charlatan, and some smart people adore him. Both good and bad people love Azra.

The illusion of freedom

He was sometimes interpreted through a kind of revolutionary symbolism, but, in reality, he was far from it. After all, he never promised he would lead us to the barricades. He was willing to be a messenger of freedom, but he always insisted it was a phantom of freedom, an illusion of freedom. People sometimes don’t need freedom; maybe they wouldn’t even know what to do with it, but everyone always needs the illusion of freedom. When choosing that illusion, Johnny is a good place to begin. His songs will forever remain good. There will always be bad regimes; Zagreb will always wake with the first grape rakija; we will all always have a Miki or a Kip and dream of having someone to sing “Ako znaš bilo što” to, drink with on a Sunday afternoon or vanish into the night with. Johnny’s songs belong in any time that yearns for freedom – even when it seems no one needs this freedom.

Such songs can be found throughout his work, in every phase, sometimes more and sometimes less – probably depending on how (un)free Johnny felt at a given moment. He was the last Yugoslav hippie of the 20th century. No one was caught more in the fever of those magnificent years than him: San Francisco, Che Guevara, the Beatles, the final of the World Cup, students, Tito’s speech saying the students were right. All of this would later follow him throughout life. He was a hippie; everything else is genres. Already on his first single, it was clear he was greater that genres. It was a novelty at the time when he appeared on the scene. Until then, there were strict genre divisions in Yugoslavia. Johnny had all these opposed forces within himself.

Testing the boundaries of freedom

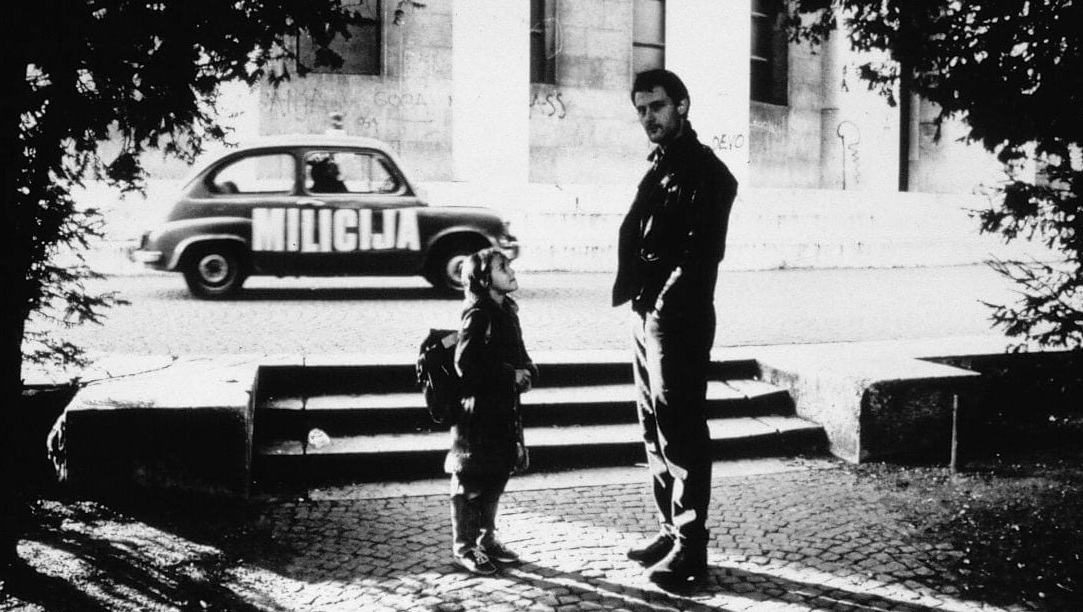

He had three phases in which he experimented with his feeling of (un)freedom. In the first, which lasted from the single “Balkan”/ “A šta da radim” to the album Filigranski pločnici and the single “Sloboda,” he tested the boundaries of his and our freedom and, in these experiments, would go further than even he could imagine. Even before he would take a guitar in his hands, the audience could notice there was something charismatic in him. Calling for an awakening of consciousness, he seemed to have a sign on himself that the audiences recognized and followed. He had the ability to captivate and draw in. He went on the stage to entertain, and then he would speak. As the first serious Yugoslav protest singer, he had the power and role of a Yugoslav Bob Dylan. The audiences, who could then very quickly and quite precisely recognize fakes, understood him immediately. A star was born.

In the second phase, lasting from the album Kad fazani lete to his final emigration to the Netherlands, he was disappointed. He was convinced we had failed him. He wanted to change everything, and it seemed to him he had changed nothing. In reality, he could not yet see that he changed a generation of people that would become artists, sociologists, historians, cultural workers in general. “It is that capillary change that changes a society in a provable but almost invisible way,” Đorđe Matić explained. “Johnny brought awareness to a part of a generation that would otherwise have no one to follow, and he was more important than professors or politicians and even writers and intellectuals,” says Matić. Culture before and after Johnny, Matić concludes, is simply not the same.

That was the time when he started to travel, first to the US, then to Germany and the Netherlands. There he realized there was and could not be any “general” freedom; he realized freedom was individual and every person was as free as they believed they were. The realization he had to pay taxes on his sweat killed his last illusions. This resulted in him declaring a dubious moral superiority with which he struck at everything around him, and, like an autocratic leader losing his mind, he talked more and more, it seemed, to himself, in some secret language of his own.

He made mistakes, of course, like everyone else. He tried making it in the world in the wrong way although he had almost an ideal path ahead of him through what he had imagined with the Balkan sevdah bend. But, although greater than genres, he succumbed to genre. He spent a huge amount of money on nothing – like many before and after him, after all. He quarreled with everyone. He believes that his belief he was robbed is a sufficient alibi to justify him to himself.

Sometimes it looked like he needed a caretaker in life – and that turned out to be true because Johnny has voluntarily been living under the care of his wife Josephine in her house in Houten in the Netherlands since 1991. There, in the words of his once best friends, “he is developing his specialness.” Occasionally, when he feels the need for music, he takes a guitar and records himself in the small, makeshift studio in his room. In recent years, the recordings have mostly not been his songs. He went from someone who wanted flawless sound to someone who makes technically faulty recordings. Nothing matters anymore, neither science nor technology – all that remains is pieces of his soul that he finds in these songs, tears from himself and records. If you catch them – they’re yours. That is Johnny’s third phase. In it, he achieved the apparently impossible: chained with unbreakable chains, he is as free as a bird because he is finally protected. He can say what he wants, write what he wants, sing what he wants.

The myth of Johnny

Did he have to leave? He had to. His mission ended in defeat. He warned there would be a war, and war happened. When it happened, Johnny would have had to choose a side. But Johnny knew that only he, Bora Čorba and Nele Karajlić must not choose sides. Bora and Nele chose sides, but Johnny didn’t want to have a side because only he is Johnny. Not having a side, however, is never good enough. When he feared he might get killed by a stray fan – maybe because he hadn’t chosen a side – we thought he was crazy.

All this only feeds the myth of Johnny. Of the several thousand pages written about him so far, barely a few hundred are about the work, and barely a few dozen are about the person – the rest are about the myth. Of all the heroes that were mythologized, he had the worst treatment. The myth of the living Johnny is greater than any myth about dead heroes – which is practically impossible. According to the tenets of the Yugoslav school of mythology, even today, Johnny has no right to a personality – his sacred duty is to remain a myth. In all probability, it will remain that way, forever.

His work does not age, at least not more than is inevitable. His work is superior, still more powerful than his many criticisms of himself. Of the several thousand pages written about him, there are few that capture at least a small piece of his nonstandard configuration. And his work still gains new followers – fewer than before, of course. He is still a source of new inspirations, although we have less and less insight into them. Such are the times. However, perhaps no one had as many followers and imitators as he did.

Of course, none of them is like him. No one will ever be like him.

Translation from Croatian: Jelena Šimpraga

This post is also available in: Hrvatski