Marking the centennial of the founding of the magazine Zenit and the cultural heritage of the Zenitism movement, the Academy of Fine Arts of the University of Zagreb and the Faculty of Fine Arts of the University of Arts in Belgrade cooperated on an interesting art project – Zenit 21/21.

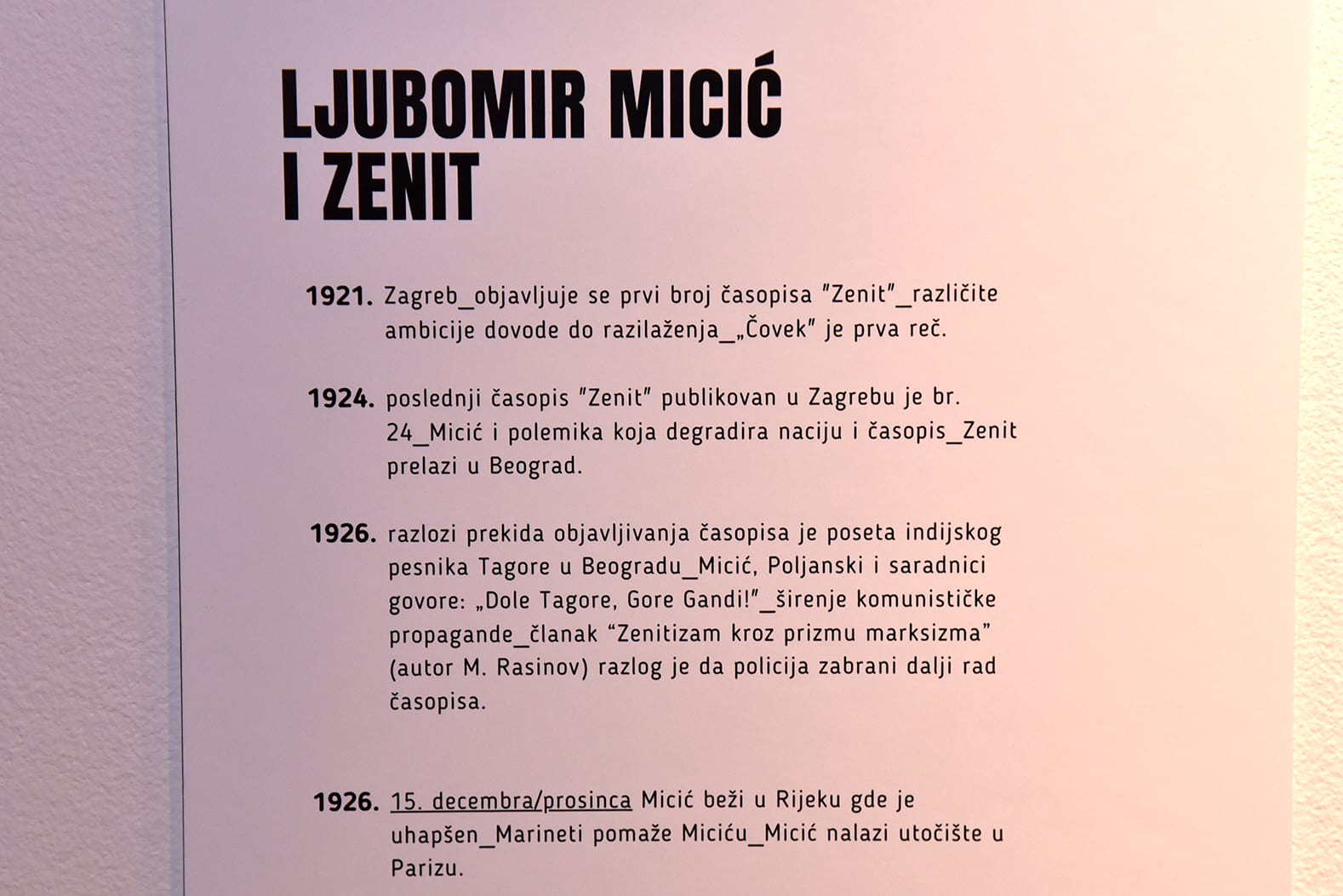

During its only five years of existence, the magazine Zenit with its 43 issues had an immeasurable influence on the artists connected with it. It was oriented towards new media and playing with form, and some of its collaborators were Vladimir Mayakovsky, Wassily Kandinsky, Kazimir Malevich, Egon Schiele, Marc Chagall… However, due to misinterpretation, a contentious quote and promulgation of communist ideas, the magazine was banned, and its editor, Banija native Ljubomir Micić, banished. Nevertheless, the heritage and influence of Zenit and Micić continue a century later, as this project also demonstrates.

Young people gathered around Zenit after a century

In Zagreb in mid-April, an event featuring lectures, public discussions and performative walks was held, and in Belgrade in mid-May, an exhibition of works by students and young artists who participated in this collaborative project will be held.

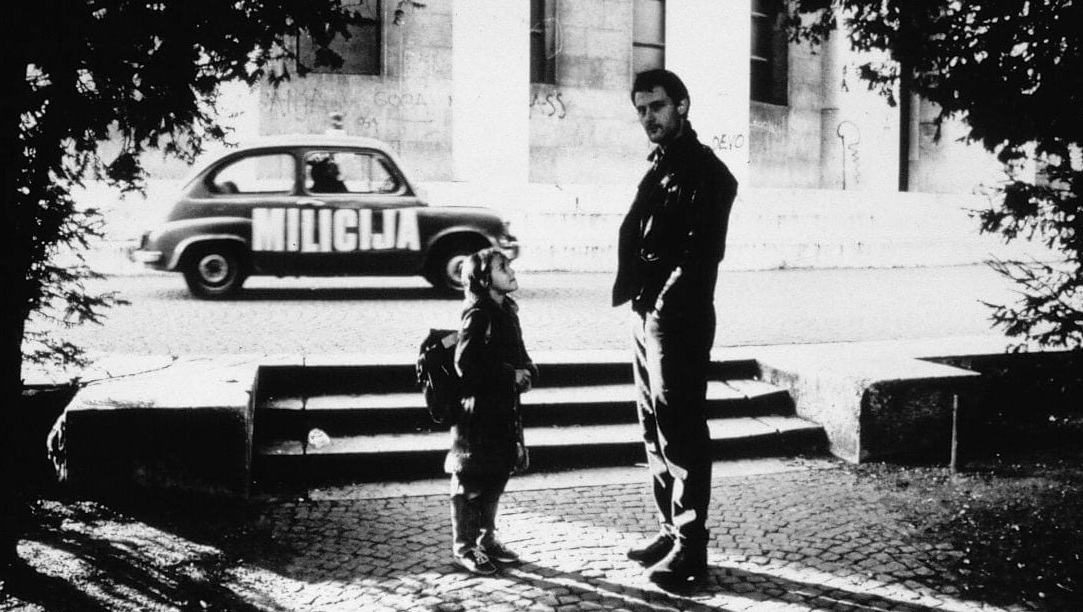

The starting point of the project was the graphic novel Slobodan pad (Free Fall) by visual artist Vladimir Veljašević, professor at the Faculty of Fine Arts in Belgrade, which serves as a pictographic guide and reminder of Zenit and the life of its founder and editor, Ljubomir Micić.

“Zenit is a phenomenon that, through its orientation and promulgation of progressive ideas, then as well as now, attracts young people with its energy and bizarre constructions which are regularly against the tide. It almost heralds punk in its early phase. It is definitely interesting to current generations, and I hope they will form their artistic practice on its foundations, but according to today’s standards and without compromises imposed by institutions,” Veljašević says.

A cultural good transcending current narratives

His colleague from the Academy of Fine Arts in Zagreb, Professor Josip Zanki, considers Zenit a cultural good that transcends current political and national narratives. He believes that cultural cooperation between Zagreb and Belgrade institutions should be built on positive points of our common past.

“Zenitism is relevant today because at the time, in a rural Balkan country, divided along national and religious lines and founded on a premodern hegemony of tribal elites instead of on the social contract, it managed to create an international, original and astoundingly inclusive cultural good. It is simply a miracle, and miracles live in the collective memory,” Zanki points out, and Veljašević adds that Zenitism “as any wildflower, has retained its local fragrance, which is recognized as original even today.”

They both agree that Zenitism as an avantgarde movement was an internationally recognized participant of the artistic revolution from the beginning of the 20th century, that it undoubtedly contributed to the spread of new ideas, and that it represents a foundation for modern art. However, they are skeptical about whether such a phenomenon would be noticed at all in today’s sea of information.

“We live in the postindustrial society, in the age of memes, influencers and the viral. The time of great narratives is gone, in society as in art. Art groups can no longer produce Manifests, not because they are unable to write them, but because we no longer have the tools to believe in them,” Zanki says.

Primitive for some, uncorrupted for others

A century later, the editorial office of the magazine Zenit, which was based in Belgrade and Zagreb, is the motive for a renewed cooperation between these two cities. Although the project speaks about a time long before them, young people, artists who had much to say and understand in Zenitism participated in it.

“I followed my dad, his behavior and his days in an observational way, but with warmth and intimacy, recording him and writing down statements and conversations. In a kind of ethnographic diary, later produced with screen printing, I follow what he says, be it reminiscences from his youth or moments that would otherwise remain unnoticed. Some are bizarre, some are crude, some simply simple and without political correctness, but, in their simplicity, they show the reality of the idea and life. That is why the movie is left in a raw state, without too much editing,” Academy of Fine Arts student Josipa Škrapić describes her work in this project.

The starting point and connection to Zenitism in her work is Micić’s barbarogenius, the Zenitist notion of the man who balkanizes Europe and thus revitalizes it.

“For some, he is a barbarian, a primitive, and for others, he is a person uncorrupted by society’s influence. Simple people, rich with their own experiences and approach to life, delight me almost to the level of sensation,” Josipa says.

Her colleague from the Belgrade Faculty of Fine Arts, Luka Višnjić, found inspiration in the relation traditional-contemporary.

“Since alongside painting and video art I also work in graphic design and illustration, my theoretical part examines the phenomenon of the use of graphic design in the magazine Zenit. My artwork will be connected more to the emotion of Micić’s idea of Zenit and the balkanization of Europe, concluding with a video piece titled Šibica (Match),” Luka explains.

Young people defending shared cultural heritage

The professors say that the project includes students with research experience enabling them to work on specific phenomena within Zenitism. Alongside Josipa and Luka, these are Željko Beljan, Tin Samaržija, Elena Štrok, Dragana Lukić, Sonja Lundin and Lazar Stojić. They have contributed to the contemporary interpretation of Zenitism and its heritage in an authentic way, not letting it fall into oblivion.

“The collaboration with my colleagues is the best, most useful thing I will remember from this project. I can say for each of them that they are involved in serious artistic work, and the works they have prepared for our joint exhibition are especially inspirational for me. I cannot wait to stand shoulder to shoulder with them on May 18 at the FLU Gallery in Belgrade,” Luka says, while Josipa also expresses her satisfaction.

“I am glad that the cooperation between the faculties of the two countries is finally established, especially since the theme of the project can be widely applied to the relations between other Balkan countries. We are opening a space that is persistently subjected to restrictions, divisions and the renouncement of one’s own heritage, which we emphasize as a cultural good,” she concludes.

“In search of man” for a whole century

The leitmotif running throughout Zenit, as well as Veljašević’s Slobodan pad, is the ad “In search of man”. A century later, this ad is still relevant, and it seems that it has acquired an additional meaning in the context of today’s distancing and alienations.

“I think we will always search for people, sometimes be disappointed, but sometimes also delighted, and not only because of the Covid year, which has really only alienated us physically. On a more important, emotional level, we have always been alienated and will be seemingly forever – we will be the most invasive and corrupt species; we are flawed precisely because of our intellectual capabilities and advancement. The act of searching for man in others is a good direction, and I hope the ad will be relevant in the next century as well,” Josipa is convinced.

Asked whether she thinks there is today any media, group, individual or movement that can be influential in a similar way to Zenit, Josipa points out the specific characteristics of the current socio-historical moment.

“Zenitism used to stir things up, and those who were neutral were forgotten in the political discourse. I think we currently have many influential groups and individuals, but they are active on a local level, which is fine for me. We still live in a global village, and although information spreads much more quickly and frequently, saturation also happens more quickly,” Josipa concludes.

Her colleague, Luka, adds that the fact we could move and socialize more freely before the pandemic does not necessarily mean we were more humane.

“We can see that again on the example of Zenit, which is for me a kind of mirror of the times. As Džoni Štulić said: “Azra – that is me,” we can say the same about Micić: Zenit – it is Micić. The way Micić was disqualified from the cultural scene of the time reminds me of today’s trend of targeting undesirables in the media,” Luka says.

Fight for humanity through art

In the introductory text in the first issue of Zenit (1921), its editor Ljubomir Micić writes that “we enter the New Decade, and we must go beyond Yugoslavia’s borders (…) We enter after enduring suffering and transformation. We enter crippled and hurt as people, but within us is the strength of those who have suffered, were humiliated and stoned at the pillory of Europe. Let our entrance into the third decade of the 20th century be a fight for humanity through art.”

Our interviewees believe that, although artists do not necessarily have to reflect the contemporary trends in society, these words by Micić represent a reminder for contemporary artists, but also for anyone else from this region.

“We often tend to label ourselves through the hurt inflicted on us by others or ourselves, while we neglect or even run away from the richness this region offers us culturally. I believe we have now stepped well into the 21st century and are ready to act as people without the burden of -isms,” Josipa says.

Her Professor Zanki agrees with the end of Micić’s quote, but not with its beginning.

“I don’t think that all the nations who lived in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia after the First World War were more degraded or suffered more than other peoples of Europe. The fight for humanity through art is possible, but only if it creates social change, if it acts not on the principles of neoliberal social elites or false activism, but from the grassroots level, as an exchange between different participants. The way social equality is organized in Zapatist territories in Mexico. From Zenitism to Zapatism,” our interviewee concludes.

This post is also available in: Hrvatski