Always around this time, in the grey and darkening days of the second half of November, the official procession towards a point in the extreme east of the country begins, a point in the plain near a great river and an irrevocably ruined and destroyed city, in order to mark the date and keep remembrance of the terrible days of almost three decades ago. During these heavy and gloomy autumn days, when a sombre veil hangs over everyone and everything and people fall silent as if according to some unspoken agreement, the same songs are heard on radio stations, songs that remind us of that time, and chief among them is that one song about the plain. Others join it, very similar and written in a collective key, from the position of the victim, just only towards themselves and their side, exclusive. For one day, they remind us of and try to bring back that state which cannot be brought back. They try to bring back the time when conflict, ethnic unity and a unanimous position on the causes of all that happened achieved something else as well – a complete severance of contacts and communication with the opposing part of the country, which was at the time, at least on paper, still one country. In just a few months, an unknown territory began on the far bank of the Danube, and in the collective consciousness and the public, but also private, consensus of one side everything from the other, erased enemy side vanished. One by one, people, places, notions, geographies, regions and concrete forms became a kind of immaterial, enchanted space that people do not think about, but about which they “know everything”, they know it is no good. It became an abstract space without memories, as if everything was covered by the same thick and sombre fog and darkness, as if places and buildings on a film strip were erased and retouched one by one, leaving nothing but empty space, regions and paths without people. Or, if there were still people, they went from familiar faces of acquaintances, friends, colleagues and kin to faceless figures with bodies and movements, but with erased personalities.

The music of collective suffering

The music heard in Croatia every year at the end of November, be it mourning or rousing, marching music or ballads, implies this time and brings back the atmosphere and remembrance of one’s own suffering and the time of complete and permanent severance from and forgetfulness of the other side. It is music suggestive of the period of collective suffering, destruction, gunfire, wailing, tears, the hiss of grenades and artillery shots, or that dreadful silence in between. With a few exceptions, lyrically these songs, along with taking the attitude of absolute personal innocence and victimhood, also pretend to be against war.

These songs suggest that there was no one on the other side to hear, feel and sing an antiwar song

But not only that. These songs directly and indirectly suggest something that the media and institutions have claimed for years: that there was no one on the other side, in the circles of singers and authors, representatives of urban and popular music like their authors, and especially in the circles of rock and roll music as the best and most beloved common element and a unifying factor for the whole former country, to hear and feel, if only so, from a privileged “safe” distance. The message was that there was no one on the other side to write an antiwar song and that even those that could and should have, of whom it was expected, did not react. It was expected especially since only until yesterday they had been equally loved here, if not more, and because of that it was their duty to say something symbolically, metaphorically, poetically, through song – through words with a melody. There was another, moderate, “rational” approach, which, with feigned or real effort and a demagogic “generosity”, allowed the possibility that the enemy, demonized by the propaganda, does have the human capacity to feel the suffering of the other, until recently close, side. But the conclusion here was the same: these rare ones, who were once the best, also fell silent and said nothing, meaning that they did not clearly and sufficiently condemn themselves and “their side” (even though many did not belong to any side); in other words, they betrayed and disappointed in this sense as well, “like all the others”, like the evil and he worst with whom the bloody battle was fought. Songs in November of every year say that even those who should not have, kept silent.

But was that really so? One could say that at the beginning and during the first, most destructive period, this was true in the most literal sense. But this literal sense tells us nothing. For if nothing was said right away, it was not for the reasons that this side assumed and the other side was reproached for.

A moment of silence

Yes, there was silence at first in those who were expected to say something, or rather, sing something, but for other reasons. There was silence due to astonishment, disbelief, shock and the inability to articulate something like that at all. There was silence because there was no direct danger and no sense of a fast flow of time, so people could stop for a moment and think that which could not, would not or should not have been thought on this side. There was one question that came up only on one side, and it was the main question without an answer: “What is happening? What happened?” Such a question is the privilege of those who still have enough peace to ask it of themselves.

However, after that, when the initial shock settled a little, people started articulating the shock, confusion and fear that all this produced in them. It shook their souls to see, suspect and hear what was going on in their neighbourhood, in places where until recently they had freely walked, played, sang and were loved, places that were equally theirs, a part of the same country.

The question which an ideologised and dogmatic consciousness did not ask itself, but the artistic one did was: is it even possible to write something about events so unfathomable? How do you write about disaster? How do you aestheticise something that raises the deep moral question of whether it should be aestheticised at all? Secondly, even if you attempt to do it, how do you do it justice? How do you avoid falling into the trap of kitsch? How do you avoid devaluing what must not be devalued with tasteless gestures and poor expression?

It was enough to see what the songs of the side that felt like the victim looked like – almost without exception it was kitsch, sentimentalism, poorly written, shallow lyrics and textual and musical clichés.

If we look today, it is fascinating how diversely, heterogeneously and in how many poetic variations the authors “from the forbidden side” reacted to the horrifying autumn of 1991 and the years after it.

City man under the blue sky

Those whom it most concerned reacted first, and in the following case – sarcastically. Obojeni program from Novi Sad wrote a song with a deliberately clichéd title – “The Sky Is Blue”, but in the song the author, Branislav “Kebra” Babić, through indirect, hermetic images and recitation – which is a stylistic feature of an alternative musical style, but is also an imitation of marching and military tempo – concealed a story about mobilisation:

“That morning I got up

Received a strange letter

I understood it quickly

I kept the secret

Along the way I wondered

If I had brought everything

I could not think about

Whether I would come back”

When the song reaches the chorus with the “blue sky”, we realize that the blue sky is a metaphor for the wish to live in its most basic form: “The sky is blue, but I am glad”. It is an expression of almost childlike innocence. At the end of the chorus, still reciting, the singer sings one of the most subtle poetic images, a mixture of associations and reality, a metaphor for the violence of throwing the city man into an environment where he does not belong – outside of the city. He expresses his estranged and ironic impression of nature, which, instead of romantic harmony, becomes a violent stage for gunshots:

“This green grass

Hasn’t been mowed in a long time

The maid uses the pitchfork

To make my bed”

The first song about the war has perhaps remained the most effective to this day, in spite of later songs which were lyrically and musically better executed.

„And I am called to war – the horror and the terror“

It was not the only song about forced mobilization. At some later moment there appeared a song with a powerful chorus in the innocent performance of the harmless Dejan Cukić:

“I would like to sing a little more

For there is only one life

And I care about it

It is valuable to me”

What is unknown on this side until this day is that these inspired lyrics were written by Bora Đorđević himself. Yes, the same notorious Bora Đorđević, prohibited and marked in absolute terms as permanently negative in the Croatian public.

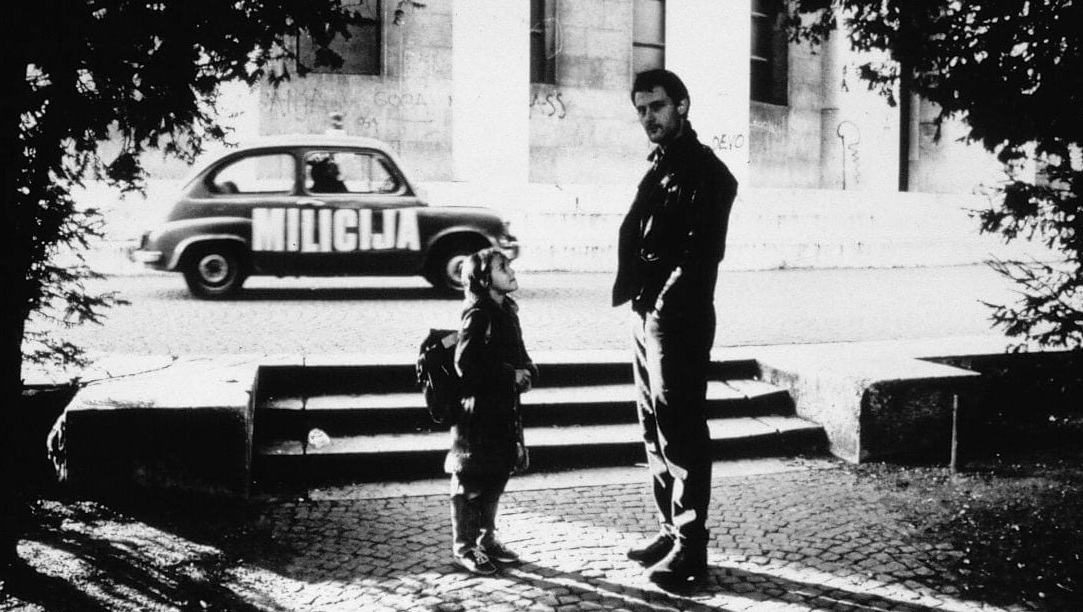

Antiwar slogans on wheels

Not long after that the representatives of the so-called alternative part of the Belgrade rock and roll scene performed a protest action against the war by driving a truck through the streets of Belgrade and singing a hastily made song with a message. The project with the three most famous members of these bands – Ekatarina Velika, Partibrejkers and Električni orgazam – was titled with a humorous, silly and quasi-vulgar anagram: “Rimtutituki”. They had good intentions. However, the result was inversely proportional to their status, influence and the reputation of their music: it was immature, confused, misdirected and unintelligent, but apparently the only thing they were capable of at the moment. They could not do better. They also responded to war slogans by reciting directly and without hidden messages, which was good and necessary: “no brain under the helmet” and “shoot less, shag more”. Looking back today, we can only feel sadness and discomfort at these completely disheartened, desperate voices of the allegedly most conscious part of that generation and their complete inability to express themselves when it was most needed. It was not much, barely more than nothing. But it was still more than nothing. There was still one “no!” in this dumb street recital when a “no” should have been said.

What stands out in this sad “happening” of driving down the streets and making noise to warn the people, at least for a moment, not to rush into horror and violence, is the tragic face of Milan Mladenović with an ironic smile, behind which stood a higher intelligence and the spasm of a man who feels in himself a deep despair, who, even when he smiles, has subtlety and knows that it is the smile of a loser and the smile of deep pain. This smile shows the almost impossible ability to reject in that moment the almost absolute self-involvement that addiction creates and to feel and see the scale of the collective common catastrophe. This is the characteristic that separates the special ones and the best ones from the rest. It is the ability to rise above themselves, their weaknesses and selfishness, to step outside of their own closed world and feel the outside world with all its collective, social and historical implications, and to feel responsibility.

Words emptied of meaning

That is why he gave his maximum through his band, even as he suffered various misfortunes, of which this collective one was, perhaps, emotionally the most difficult one for him. With the sensibility of a true poet Mladenović sensed, apart from the horror, the danger and the darkness, something else, essential for a man of words. He sensed the emptiness of speech, the pollution of language with ideology, propaganda, deceit, manipulation and hatred and the exploitation of the meaning of words, which turned into their own opposites. That is why he, an author known and loved for the richness of his hermetic and enigmatic poetic images, titled his album and his song not with a lexical word, but only with an onomatopoeic, consciously infantile expression, a metaphor for the powerlessness of words to express what was happening then, in 1991: “Dum dum”. In the song, the lyrical subject is not the author or someone close. Rather, it seems that the song is from the position of someone participating in the collective madness and contributing to the evil:

“I will hate icily cold,

with a heart with seven crusts,

I will shoot straight in the back,

I was born to rule”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z2a5O2_GGJM&feature=emb_title

On the same record he also sang from his own position, from the distant metropolis and in an urban, expressionist style in rhyme, which was rare for him. He imagined and felt what it was like where the horror was happening. There was destruction and death equally in nature and in cities, which he expresses in images for both:

“A sound is heard

That reminds me of a roar

Tree by tree is torn down

The wailing wall dies, dies alone

The beast dies”

The use of the word beast (“beštija”) in the last line by Mladenović, a speaker of the eastern variety of our language, for which this word is unusual, is almost grounds enough to write a separate text about the author’s identity.

Circles of hell under a happy cover

The biggest teen idol of the 1980s, also beloved by most people who liked quality pop music, Momčilo “Bajaga” Bajagić had, in those desperate crisis years, several songs that reflected the conflict between those until recently closest with each other on his record, which had a joyous, lively cover, just as its author is.

He also imagined and placed war in the dichotomy of two different circles of hell, the natural and urban one. The first hell was in villages, woods, fields, ravines and mountains:

“Hundreds of kilometres from me

Or simply said, on the other side of the river,

Where nightly souls, mountains and houses burn

And some lamps, now so far away”

The other, more terrible hell was the one that struck at the centre of civilization, at cities. In the last stanza, the author says goodbye to them in a fierce tempo, but with immense sadness:

“All those streets that I knew well

That no one will walk this night

All those people that I loved very much

And that I will never see again”

It was a rare luck that the last prophecy did not come true, which no one could know at the time.

In the chorus of the song Bajaga called upon, as many did at the time, the highest Power, which seemed to have given up on Yugoslavs in those days:

“Where are you, God, where are you?

Black days follow one another.”

It is therefore not strange that he ended the album with a prayer and the powerful and frequently used symbol of peace. But is it coincidental that, precisely at that moment, he used the Christian symbol of the Holy Spirit – the symbol of the dove, an indispensable part of Catholic iconography that is much closer to Catholics than to the denomination that the author belongs to, at least by heritage? In the same song, he metaphorically and stylistically ends his gospel in a dramatic way, but, rising above sadness and tiredness, also unexpectedly joyfully, with true faith mixed with despair. He speaks, most importantly, to those most fragile but also the strongest, for they are the only future – children:

“Send your grace

To all the kids of the Balkans,

Feed us, peace is our food.

Dove, from my heart

Flutter off into the world.

Let the sun rise for us

And heal our wounds with your touch

Make the years of evil soon fade away…”

Prayer to the common God

He was not the only rocker to use this invocation, which, until recently, had been used almost exclusively as a romantic effect when speaking of female beauty.

Now the invocation came from the bottom, humbly, helplessly, out of a need for hope. And it was not just any God, but the Christian God, for even then, when the nations fought each other, he remained the same, one common God of both the western and the eastern denomination.

“Mother of God” instead of the usual “Bogorodica” tells us what the band wanted to say and which city they wanted to portray as the metaphor for destruction

The most peculiar and perhaps the most powerful allusion to the site of destruction and urbicide in the east of the nascent country appeared a little later in a song by the Belgrade Partibrejkers. “I want to know where this path leads me and my life” the band’s frontman Zoran “Cane” Kostić nasally sang, almost recited. The chorus of this song could make it seem like a typical rock and roll anthem to personal freedom and staying true to oneself, in the tradition of rebellious rock and roll songs and their refusal of community in the name of the individual: “to be the same, special, free, to be only one’s own”. It would have remained that, as powerful as it is, if a part had not been inserted – a recital, scream, prayer and invocation of the metaphysical phenomenon and religious notion:

“Mary, Mother of God – do you see what they are doing with your children!” the singer wails through his teeth, while in the background the rhythm guitar plays in bursts mimicking the shots of a machine gun, and the cacophonous, high-pitched whistle of the solo guitar imitates the hiss and the roar of a grenade. This kind of sound and this choice of words in a song by a band from a nation where Marian devotion is not a prominent element of the people’s faith and where the usual term is not Mother of God, but “Bogorodica”, is indicative of what the band wanted to say and which city they wanted to portray as the metaphor of destruction. It is a great and powerful poetic image, and perhaps the greatest authorial and imaginative feat of this band.

Authors, poets and songwriters tried – more or less successfully, some more easily, some with more difficulty, some more openly, some through more hermetic images – to express the inexpressible.

No one is freed – there are only “eternal hostages of the nightmare”

In a classic poetic, prosodic, expressive and formal sense, no one achieved what probably the most talented among the songwriters, and possibly the only true poet among them, did. Not only because of his calling of the true poet, but because of something else as well. It could not have been a coincidence that it was precisely him that wrote the most harrowing song about the terrible autumn of 1991. Culturally and geographically, he was the closest to that circle – a man from the plain as well, nurtured by the same customs, raised in the same atmosphere of a life of a slow tempo surrounded by fertile fields, with the same speech of elongated syllables and the same mixed heritage. He came from the same Pannonian plain as the city that was reduced to dust and humiliated for both of its peoples, and that he put into song like nobody else.

The poetic images in his lyrics, built on the notions and folklore of that region, Đorđe Balašević – for it is, of course, him – did not have to borrow or imitate, for they are within him, in the “genes saved in him”, to use his own lyrics. The song begins with ethereal female voices, but those voices are dark, tragic, with a liturgical echo. They are followed by a guitar chord and then by the voice of the singer, singing lines with long pauses between them and bringing, again, a powerful metaphor from nature:

“Sullen and silent

The poplar cloven by thunder”

In the next line we see that this is a description of a man and that this “poplar” is “staring into a deep, deep glass”. The lyrical subject says that the stranger “looks normal” to him, until he notices – in the line that carries the title of the song – “the Moon’s reflection in his eye”. The Moon – “Luna” – “lunatic” – madman… The exchange of words and lyrical subjects continues in the dialogue with the stranger at the bar in a city atmosphere, and the man’s story becomes ever bitterer until, as the song grows, it pours out in an anaphora in the stanza before the chorus what it is all about:

“You don’t know what it means to kill a city

You don’t know the frights of muddy trenches

You don’t know what it means to sleep now

When I close my eyes – nothing, except those roofs”

Only at this point in this incredible song does Đorđe Balašević let us know who he is talking to – a soldier returning from the front lines, a war veteran. At the moment when we are shaken by this revelation we have already come to the chorus, unparalleled in the history of songwriting in this region:

“When I close my eyes,

villagers are gathered in work across the sky,

living rooms spread their scent,

across the sky wedding sounds ring.

When I close my eyes,

faces pass across the sky,

a swarm of tamburitzas tremble,

the Danube rolls the mother-of-pearl”

In the middle stanza, the narrator, the former soldier who “survived” in quotation marks because he can never be wholly alive again after everything he saw, nor whole again because he is cracked and broken, a “living dead man” who is aware of what he is, says it himself:

“You don’t know, no one is freed,

My every silence is torn by a grenade,

The first one shot was saved,

And all the rest are eternal hostages of the nightmare…”

The last chorus:

“When I close my eyes boats appear in the sky,

Bells, barking, fights between neighbours,

The scent of freshly ploughed fields.

But when the sun rises, winds whine from the river

I know, it is the water vilas grieving

The Danube rolls the frankincense”

What an incomparable series of images it is, moulded from the essential cultural notions of the region and then elevated to a poetical and even metaphysical level: first “boats appear in the sky”, like in an upside-down world where the two extreme points, one upper, one lower, are water (river) and sky, like in a Chagall painting. Then follows an ellipsis with a series of images from the quiet, everyday life of a Pannonian town – “bells, barking, fights between neighbours”. However, these images can also be read differently: the sinister sound of bells tolling mixed with the barking of dogs as the background sounds of war; the “fights between neighbours”, once funny, like from a novel by Stevan Sremac, now the sign of hatred between closest neighbours. All of this is enveloped by the unceasing flow of the great Danube, which “rolls frankincense”, until we see the unearthly image of ground crumbling under artillery shots. And above all, in the most moving image, so Slavic and pagan, the “water vilas grieve”, with a sound never before heard, the sound of unearthly, incorporeal beings that lament the dead, a whole city and civilisation.

“Opelo” and requiem in one, for in this threnody for a city the author laments and grieves for everyone, unreservedly, without arguments and counterarguments, refusing explanations and justifications

When the singer falls silent, female voices are heard again singing in the style reminiscent of Orthodox liturgy. This is an “opelo” and requiem in one, for in this threnody for a city the author laments and grieves for everyone, unreservedly, without arguments and counterarguments, refusing explanations and justifications. With his poetic force, the author never mentions a single toponym or name, but we as listeners know what it is – inside of ourselves, in our never forgotten fear, in our nerves, in our heart muscle, in our chest, in the raised hairs on the backs of our heads and on our arms, in the tear that rolls down. What kind of talent was it that was able to create something like this?

We do not have an answer. But he, the author, and his song are a living, human negation of the persistent, thirty-year-long lie that “there was no one” to express this in words that are more than everyday speech and learned phrases, to sing in grief for one’s own and the others’ victims, to empathise with the others, to feel the guilt, powerlessness, despair. And, crucially, to feel for the living and the dead from the other side, to feel their sacrifice – respecting it as autonomous, separate, forever different – as one’s own as well, as a part of oneself and the loss of a part of oneself.

Translation from Croatian: Jelena Šimpraga