April in Banja Luka is full of history and celebrations. There is no lack of history in other months, either, and there is plenty of song and jest. But, somehow, there are so many celebrations this month that we sometimes forget spring has come. The Banja Luka City Day on 22 April is preceded by days moving from moderato to allegro and finishing in the crescendo of city celebrations. These are the Days of Vlado S. Milošević.

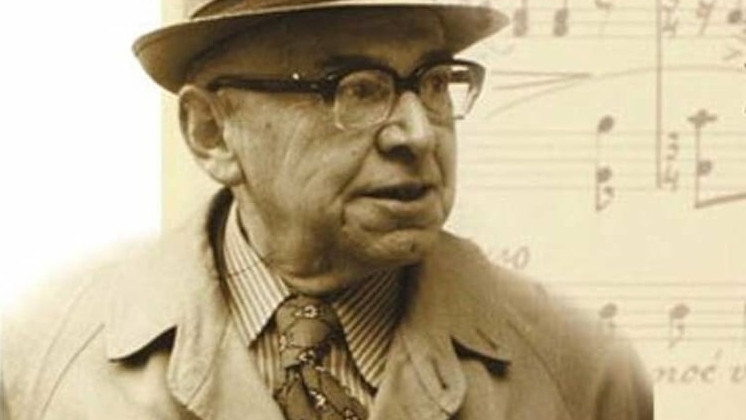

If we say it is the 120th anniversary of his birth, it is not an April Fools’ joke or a miscalculation since the year 1901 is the year of the birth of this great Serbian composer, ethnomusicologist, choirmaster, pedagogue and academician. Due to the pandemic, this important anniversary was celebrated as circumstances allowed last year. Vlado deserves much better. One year, therefore, is not counted.

His works are currently premiering in Banja Luka. The number of his works is impressive. Experts say he composed 506 pieces – everything except ballet.

Vlado left an indelible trace in Serbian and Yugoslav art. The heirs of his impressive and varied opus and his friends reminisced about this great man in a conversation with P-portal.

“Vlado Milošević was a devotee of music. Looking at his entire life, we could call him a musical monk. Exploring his artistic and scholarly legacy, I have to ask myself – when did this man sleep?” says Saša Pavlović, a professor at the Academy of Arts of the University of Banja Luka.

“He didn’t have the opportunity to attend music school because none existed in Banja Luka at the time, except for Czech music schools – Czechs came to Banja Luka at this time and opened the first private music schools. Vlado graduated from the Music Academy in Zagreb; he studied under professors eminent in the whole region at the time. He studied all the compositions of Rimsky-Korsakov and Tchaikovsky; he studied compositions of Béla Bartók and Leoš Janáček, which were ahead of their time and which we still perform rarely in our region,” Pavlović explains.

Many wrote about Vlado Milošević; those who stand out are writer Ranko Risojević and Milorad Buco Kenjalović, the founder and former dean of the Academy of Arts of the University of Banja Luka. Kenjalović had known Vlado Milošević since secondary music school. He and Vlado played in the city string orchestra.

“He played the viola then. The director of the orchestra was my head teacher, Stipe Blažević. One time, I was late for rehearsal in Banski dvor, which was then the House of Culture. After a few minutes, the teacher waved to me and told me to get my violin out and join the rehearsal. When I told him I had forgotten my violin, Vlado took his glasses off, looked at me in astonishment and said: “Went to rehearsal and forgot his violin,” Kenjalović recalls with a smile.

Milorad Kenjalović has written music reviews, among them reviews of works of Vlado S. Milošević. He wrote about the first opera of Bosnia and Herzegovina, performed in 1977, in what was then the National Theatre of Bosanska Krajina and is today the National Theatre of Republika Srpska in Banja Luka. It was the opera The Badger in Court, composed by Vlado S. Milošević based on the story by Petar Kočić, adapted by Ranko Risojević.

“He was such a simple and humble man. I tried to learn this simplicity and humbleness from him. Vlado loved to compose pieces based on texts of our leading poets. He was the leading composer in Yugoslavia when it came to the number and variety of pieces. His work grew, so he also composed my 17 Bosnian Elegies. At the time, I was a young writer with a modest opus,” writer Ranko Risojević recalls.

A true lover of poetry

They met after the earthquake that hit Banja Luka in 1969. As the editor of the reputable culture, literature and art magazine Putevi, Ranko Risojević dedicated an entire issue to Milošević. This brought him attention, primarily from expert circles in Yugoslavia. Radio Sarajevo recorded many of his compositions. Risojević would later become his first biographer, and his book Vlado S. Milošević – One Age is still the reference and starting point for anyone wishing to know about the life and work of the unique composer. The compositions The Fourth Bosnian Elegy and From the Quill of Kočić recently premiered in Banja Luka.

“Of course I am happy about it. The Bosnian Elegies are the result of the huge influence Vlado had on me, especially through the way he turned towards old sources in his entire work – towards songs from Zmijanje, which are still preserved. He wrote sevdalinke, too. But sevdalinke are traveling songs. These songs from Zmijanje started traveling only after Vlado composed music for them. I wanted us to expand it all. He was working on Mak Dizdar’s Stone Sleeper then, and then he started working on my elegies. He was a true lover of poetry. When choosing a text for his music, it was important to him to like the poem,” Risojević points out.

“Vlado kept abreast of contemporary developments in music but, at the same time, based his work on the national musical style. The biggest discovery for Vlado was Zmijanje. The journey to Zmijanje in 1940 had a great effect on him. He composed his masterpiece, Songs from Zmijanje, in 1940,” Pavlović points out.

Exile to Niš

In 1941, Vlado and his family, which was reputable and therefore among the first to be targeted by the Ustasha terror, fled to Niš. He worked as a teacher in a gymnasium. He wrote his first instrumental piece there. He returned to Banja Luka in 1946.

“He later expanded this work, both thematically and with regard to performance. The culmination is the dramatic symphony that resulted from his experience of the great earthquake that hit Banja Luka in 1969. It was all recorded at Radio-Television Sarajevo of that time. His compositions were recorded by members of the world-renowned Zagreb quartet Pro arte. Those are excellent recordings. There are still gramophone records of it. The best interpreters of his solo songs are Banja Luka opera divas – Radmila Smiljanić, Dunja Simić and Snježana Savičić,” Kenjalović tells us.

As a lover of traditional folk music and everything that goes with it – folklife in general most of all – Vlado Milošević collected the songs in four books of Bosnian folk songs. He did not only transcription there, and that was very difficult to do at the time. The areas he visited had no electricity, not to mention other technical difficulties. He often wrote the songs down while the singer was singing. That is a difficult position for an ethnomusicologist, and village singing is very unstable. He studied and collected small-town songs. He believed they were the precursors of sevdalinka songs, about which he wrote a large study that he presented at an ethnomusicology symposium in Paris. He collected songs sung with musical accompaniment. It is hard to name everything that this systematic and meticulous cultural worker did.

“We collaborated extensively on the radio program Exploring the Folklore of Bosanska Krajina. Our goal was to bring the traditional music of villages, but also of cities, to potential listeners. He wrote the script for the first ten episodes. I was the editor. Our staff meeting was on Mondays. A colleague noted in the report on our program: ‘An interesting program for both listeners – Vlado and Buco.’” As funny as the anecdote is, Kenjalović adds that this program is now valuable archival material.

He was one of the most prolific composers in the Balkans. Being very self-critical, he openly discussed the quality of his works, aware of their varied levels of quality. He last worked in the Museum of Bosanska Krajina, today the Museum of Republika Srpska. The primary and secondary music school in Banja Luka are named in his honor. He was the manager and director of the Serbian Singing Society Jedinstvo from Banja Luka, one of the oldest and most successful choirs in Bosnia and Herzegovina, which has won awards at festivals around the world. He died in 1990. He did not live to see another war. Two world ones are too much for one lifetime.

Don’t sing walking through Banja Luka

Perhaps the Days of Vlado S. Milošević are too short to say all there is to say about him. Meanwhile, we notice spring is here. A fruit after rain is caressed by the April sun. The Vrbas, in its turquoise-emerald robe, invites new couples and merry gangs to its banks to celebrate life with the sounds of guitar and song. There have always been and always will be great singers in Banja Luka. Singers from the soul. Singers with dedication. Singers immersed in the line, the stanza, the chorus, as if there never was and never will be anything outside of song.

Not for nothing was it said long ago: “Don’t sing walking through Banja Luka”, alluding to the great singing talent of Banja Luka people, evident in the names of opera prima donnas. But that is a matter for another story.

Translation from Croatian: Jelena Šimpraga

This post is also available in: Hrvatski