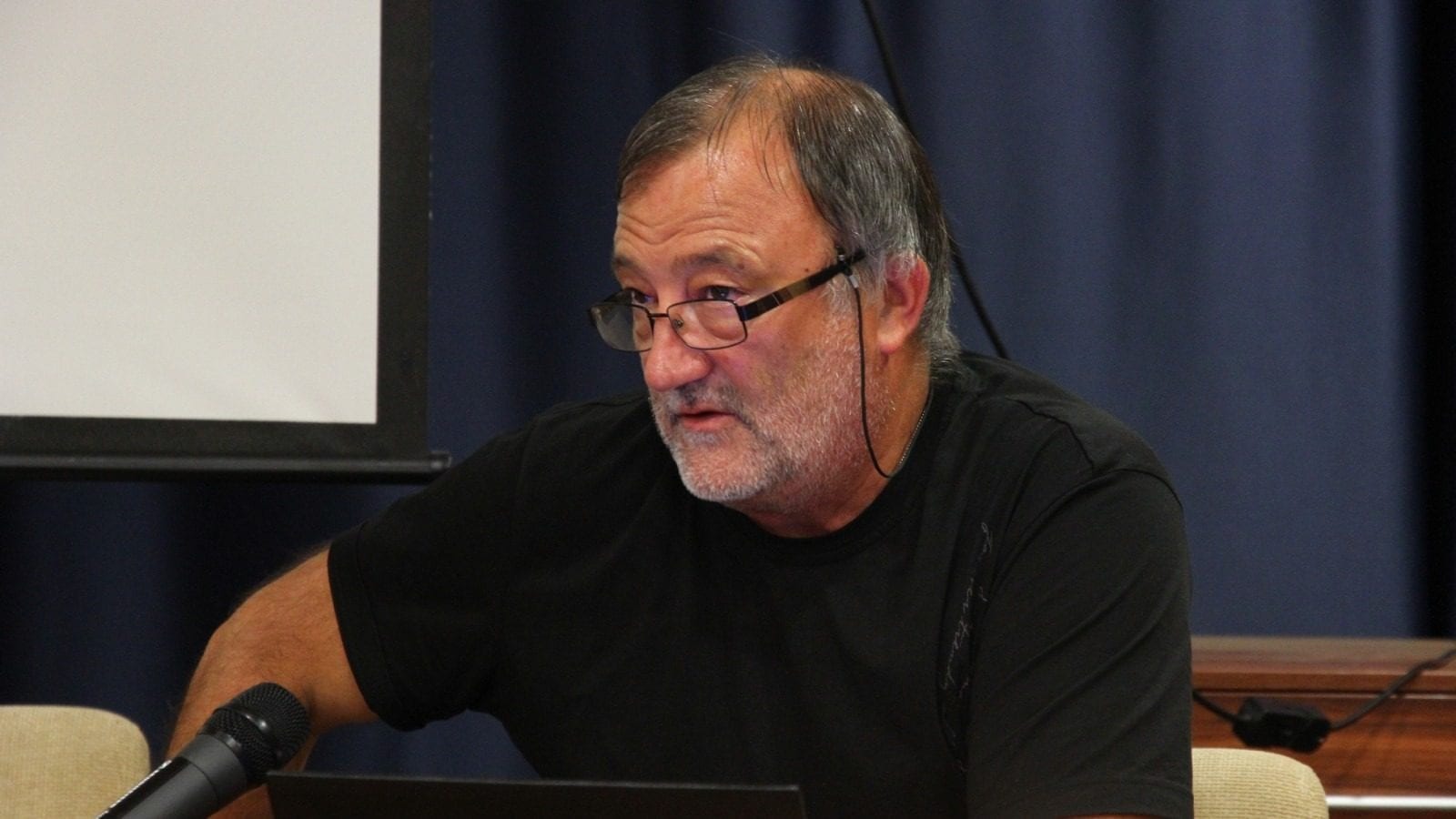

We talked to Siniša Jelušić, a professor at the Faculty of Dramatic Arts in Cetinje, about the election results in Montenegro, the cultural and spiritual traditions of this region and current conflicts, hopes and perspectives.

The past parliamentary election in Montenegro looked like more than just a change of government; it seemed to be a historic social turning point and a change in the fundamental cultural code. What is going on?

Yes, it is not an exaggeration to say that it is undoubtedly a historic social milestone because, for the first time, a change of regime in Montenegro was achieved non-violently, through the election, which is normally everything but democratic in Montenegro. Step by step, the party of Milo Đukanović (DPS) had shaped the election law to suit their own interests, which were primarily to stay in power at all costs! If an authoritarian system of government, such as Đukanović instituted, controls all relevant segments of society, it is clear that no democratic election can be expected. That is why, in spite of everything, this change really could not have been anticipated, for it seemed that taking down a perfectly criminally organized government, especially through election (with the election law and voter lists under total control, the buying of votes and electoral corruption), was impossible. Moreover, the mechanism of retaining power benefitted from two socio-psychological characteristics which are used heavily throughout the entire South Slavic region. The first is an efficient manipulation of national sentiments: the hypostasis of the “other” as the enemy who is a mortal threat to us, and the second is the proclivity towards authoritarian leaders – all characteristics of an essentially pre-civic consciousness for which the “escape from freedom” (E. Fromm) is much more important than, for example, the Christian idea of the “act of freedom”, the only act in which the individual is authentically affirmed.

Crisis of spirituality

What decided the outcome of the election?

I believe that the crucial factor for the election results and the final fall of Đukanović’s regime was the phenomenon of litije, a primarily Church-led mass protest, headed by the Metropolitanate of Montenegro and the Littoral of the Serbian Orthodox Church. It seems to me that the litije predominantly represented an awakening or a return to a religious archetype, and in this sense I see two different planes in its content. The first is a revolt out of a need for meaning by an authentic homo religiosus, whereby the authenticity of participation in the centuries-old tradition of Christian religious practice was explicitly brought into question. The second is the revolt which arises when one faces the general state of contemporary Montenegrin reality, full of political deception, hypocrisy and undisguised tycoon interests. In a spiritual sense, the litije represented the Christian communion in action, marked by a sense of togetherness and love, and no act of violence, usually very common in such large protests, happened here. I would like to point out that, alongside Orthodox Christians, who were naturally the most numerous, there were members of other faiths at the litije as well, all united in a common walk of resistance to the state of things. I found it particularly interesting that many intellectuals, both right- and left-oriented, vociferously called into question this Christian religious inspiration, expressing great regret at the departure of Đukanović’s regime because “Đukanović led us into the highly civilized society of European democracy,” and now we have a theocratic-clerical system. Some even mentioned a “Khomeinian Jamahiriya”, whose darkness, they said, swallowed us in an instant.

How do you explain the animosity of the modern man towards the categories of spirituality and religion?

That is one of the most important questions concerning the problem of human existence today. Put simply, the first stage develops according to Nietzsche’s prophetic warning that God is dead (the additional “and we killed him” in this utterance by Zarathustra is usually forgotten!). How did we kill God? Well, we killed him, I would say, by identifying ourselves as the subjects of rationality and above all as the bearers of the technical mind. Therefore the real state we live in is – nihilism. Through our absolute devotion to the material, i.e. the temporal and transitory, our existence has completely forgotten that man is only a homo viator, a passenger, in this world, and thus our existence lost its crucial foundation in the principle of eternity: Sub specie aeternitatis. Eternity has been replaced with transient temporality, but the crucial question of meaning still inevitably breaks through from the depths of the unconscious. This divide between the material and the spiritual defines the crucial crisis of spirituality we find ourselves in today.

What are the consequences of this state, in your opinion?

When this dimension of spiritual or transcendent is excluded from various dimensions and spheres, including culture and art, we come, on the one hand, to this huge emptiness and a great, gaping Nothing, and on the other, we get the “replacement”, and that is what I call the attractive pornographic, tabloid culture and the accompanying politics. Just look at the headlines – is that not the deepest humiliation of all that is human in us? I think we have come to the symbiosis of politics and the pornography of tabloids, which together completely dominate our minds and lives. Moreover, we have in accordance with this a total decline of education, as in the Bologna reform, which devalues all subjects that cultivate theoretical thinking – thinking as a discipline that goes all the way back to ancient Greece – because these subjects are declared impractical. This, in turn, leads to decreased interest from students for theoretical and philosophical subjects, which is symptomatic of the overall path of this civilization. Man and society thus become something unimportant and a cheap tool in the hands of politics and the media.

Interfusion of the East and the West

Apart from political resistance to the recent regime in Montenegro, to what extent was the mass participation in the litije motivated by national factors?

Contrary to the interpretations that it was a manifestation of “Great Serbian” nationalism, it is important to point out that the notion of Serbian identity in Montenegro is first and foremost a spiritual or cultural category, and is therefore in a sense supranational. I have here in mind the Christian spiritual principle, derived from our common basis in the tradition of Cyril and Methodius, which is for certain reasons forgotten and politically repressed today. This exceptional foundation of the development of our common spiritual tradition – the language, culture and spirituality – affirms the autochthonous Slavic identity of these regions against the centuries-old pressures from both the East and the West. In this sense, we should not forget the fact that Rastko Nemanjić, later Saint Sava, is one of the most respectable personages of Europe at the end of the 12th and first half of the 13th century in a very universal and not only national sense. He was exceptional in many disciplines, from literature, theology, painting, architecture, politics and diplomacy to medicine and law. Is it not natural for the Serbian people to celebrate him as the founder of Christian culture, and for others to view him with no less respect as well? But contrary to this, the political ideology of contemporary Montenegro has done everything to ensure that the mention of Saint Sava is reserved only for the private sphere, although both he and his father Stefan Nemanja, the founder of the Nemanjić ruling dynasty, originate from the area of today’s Podgorica (Ribnica). Moreover, as is well known, Saint Sava is the founder of the first eparchy, the Eparchy of Zeta (1219), later metropolitanate, at the Monastery of St. Archangel Michael in Prevlaka in Boka kotorska. It was from this area that his spiritual influence spread, which is confirmed by the many toponyms with his name in the area of Boka, Grblje, Paštrović and Montenegro in general.

Where lies the supranational meaning of this spirituality?

In our morbid divisions, we frequently intentionally suppress the fact that the tradition of Saint Sava is strikingly similar to the tradition of Saint Benedict of Nursia, whose Benedictine tradition is very strong in Boka. This spiritual interfusion of the East and West was not only present in Boka, but characterises the greater part of the culture and art of medieval Serbia. Let us not forget friar Vito of Kotor, the builder of the jewel of Serbian medieval architecture, monastery Dečani. Can we even imagine today that one of the most important monuments of Orthodox culture was built by a friar, who introduced clear elements of western Romanesque art into the architectural style of Serbian/Byzantine architecture of a monastery in Kosovo and Metohija? There is also the example of the famous Helen of Anjou, a Catholic and the protagonist of one of the most extraordinary medieval biographies, married to Serbian King Uroš Nemanjić I; she built the Orthodox monastery Gradac in Raška. This is the ancient receptiveness of great cultures, in which the narrow national and religious identity was put aside in the name of universal, transcendent values – something that should be a guiding principle for our time as well. Or, in the words of Saint Nectarios of Aegina: differences of faith are not an obstacle to brotherly love!

Harmony of differences

What does this complex connection look like in today’s Montenegro?

Drawing on the well-known study by Braudel, we can see a connection between nominally different types of spirituality in Montenegro which have a similar spiritual substance, something that is especially characteristic of the littoral part of Montenegro. I like applying the literary-theoretical term of intertextuality (Bakhtin, Kristeva) in its meaning of interconnectedness of texts to the theory of culture: is culture not actually a palimpsest or a text whose essence is made up from numerous other, different texts? To be precise: this thesis opposes today’s obsessive idea of the so-called pure and, as a rule, mutually opposed identities, and it seems especially applicable in the analyses of the cultural being in Montenegro and Croatia. Cultures are not mutually exclusive; rather, they are based on a relationship of interfusion. If particular national differences have to be emphasised as distinct cultural characteristics, it should always be done with the awareness of our common substances, which are frequently hidden beneath the different forms in which they manifest.

In this sense the cultural relation between Serbs and Croats, especially in the coastal region, is particularly interesting to me, and is so evident in the literary work of Vladan Desnica. We hardly need mention the example of Nikola Tesla, the son of an Orthodox priest from Smiljan in Lika, a Serb, who was deeply aware of the area of his native Croatia. Another example is the letter of Petar II Petrović Njegoš in which he writes that he is “a Serb, Montenegrin, Yugoslav and Slovin”, categories that are not mutually exclusive but correspond with each other. Njegoš, for whom Serb identity is certainly dominant, did not mind introducing into his identity notions that contain a kind of harmony of differences. In the Balkans, nothing exists of and by itself, completely separated from other cultural, national and religious identities. Historically, Croats are in a relation of correspondence with the Serbian culture in Croatia, which has been present there for centuries, and vice versa. Will we finally realize that the Other always enriches us and that rigid national and cultural divides impoverish us?

What is the Kosovo Covenant, often mentioned in the discussions about identity in Montenegro?

I think that the most complete answer to this question was given by Ivo Andrić in his famous essay Njegoš as the Tragic Hero of the Kosovo Tradition, which begins with the sentence: “This drama began in Kosovo.” Andrić points to the active Kosovo tradition in Montenegro, with a special conviction that “Montenegro is the quintessence of the Kosovo mystery.” We should remember his observation that in the Montenegrin mountains people “serve the cross and live with the Kosovo hero Miloš,” and that only in this light Njegoš’s work and fate can be understood. I want to point out that in his brilliant essay Ivo Andrić expressed the deepest understanding of the importance of the Kosovo Covenant for the spirit and tradition of the Montenegrins. I am sure that today in Montenegro’s schools this metaphysical dimension of history and existence is actively suppressed and ignored. These statements by Andrić amount to a scandal today – an ethnic Croat and Catholic wrote the most profound lines on the metaphysics of Kosovo.

In today’s world of divisions and antagonisms, what would be necessary for us to understand the categories of polyphonic identities?

We would all need a long and earnest interdisciplinary dialogue, something that is sorely missing from our education and the wider public today. Such a culture of dialogue without political, cultural and religious exclusion would be very beneficial for our world. That would also be, dare I say, very necessary for Serbs in Croatia, so that they are no longer seen as perpetual scapegoats but as friends and brothers, even with all the tragic experiences in the common past. Today’s Christians, those in Croatia among them, cannot sincerely talk about the “good Samaritan” if they themselves do not have solidarity, warmth and love for the Others. This would also entail something truly necessary for us all – repentance, as understood by Dostoevsky in Zosima’s message in Brothers Karamazov: “We are all guilty of everything!” With this invitation let us try to accept each other and achieve that which essentially makes us human. That is why the Serbian Orthodox Church in Croatia should be accepted not through distorted nationalist and ideological notions, but through the authentic messages of brotherly love this Church tries to pass on.

Translation from Croatian: Jelena Šimpraga