Can we imagine Zagreb in the mid-nineteenth century? Probably only with difficulty. Our memories, especially those of the younger generation, hardly reach as far as the last years of the twentieth century. Besides, the notion of memory is no longer an important category – we live today. Our city from one hundred and seventy years ago must seem to us almost prehistoric, although buildings and many other details in apartments, streets and Zagreb public squares from that time can be seen around us every day. Do we even wonder who the people who lived in those houses were, how they dressed, where they went out, how they behaved, if they, for example, loved the theatre? If we dive for a moment into the mists of this past, we find that in 1837 Zagreb had 15,155 inhabitants, the first Zagreb reading room and a music school with a three-year programme were opened, and the first newspaper in the Kajkavian and Shtokavian dialect was published through the efforts of members of the Illyrian movement. A shooting range in Tuškanac and the park in Maksimir were opened, and the city’s mail coach began operating, delivering mail to Vienna, Pest, Dalmatia and Vojvodina. In Amadeo’s palace in Demetrova Street, in “the house with the dance hall”, theatre plays took place. These plays did not enjoy a very high reputation because they were performed by travelling theatre companies of dubious quality and especially because the people of Zagreb wanted to see plays in their own language instead of in German. Thanks in part to merchants, craftsmen and the few members of the intelligentsia, but especially the famous Edict of Tolerance issued by the Austrian emperor Joseph II at the end of the 18th century, Zagreb gradually became what we would call a multicultural, urban environment, where balls, concerts and fine art became the main form of entertainment. The famous Balkanologist Josef Matl wrote of these important changes: “For South Slavs, romanticism actually represents renaissance and a national and cultural rebirth within their cultural development as a whole.”

Patriot and Benefactor

This important imperial edict on tolerance meant that different groups of people, including the Orthodox, i.e. Serbian population, could settle in Zagreb and that these settlers could in good faith consider themselves equal citizens of the royal city of Zagreb. There were not many Serbian citizens of Zagreb in the mid-nineteenth century – maybe a few hundred families – but their community was valued, important and had a good reputation in the city. It is stated in the book Serbs in Zagreb by Dejan Medaković that the respect that the members of the Serbian community enjoyed among the citizens of Zagreb “was won through universally accepted civic virtues, reputation and esteem”. One illustrious representative of the community was Zemun-born Hristofor Stanković, merchant, president of the Zagreb Orthodox Parish and a notable person in Zagreb of that time.

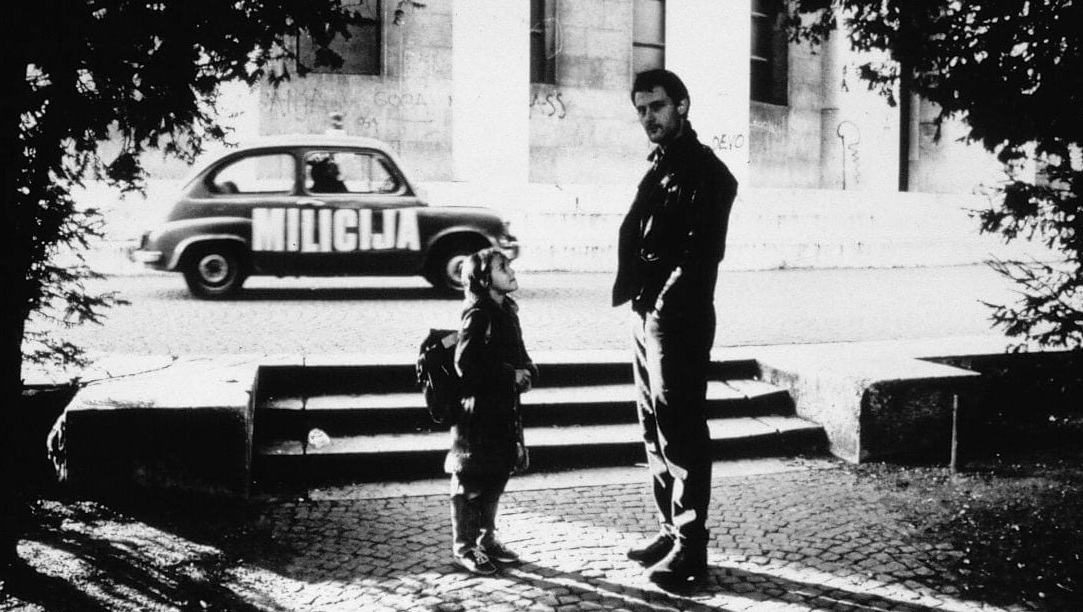

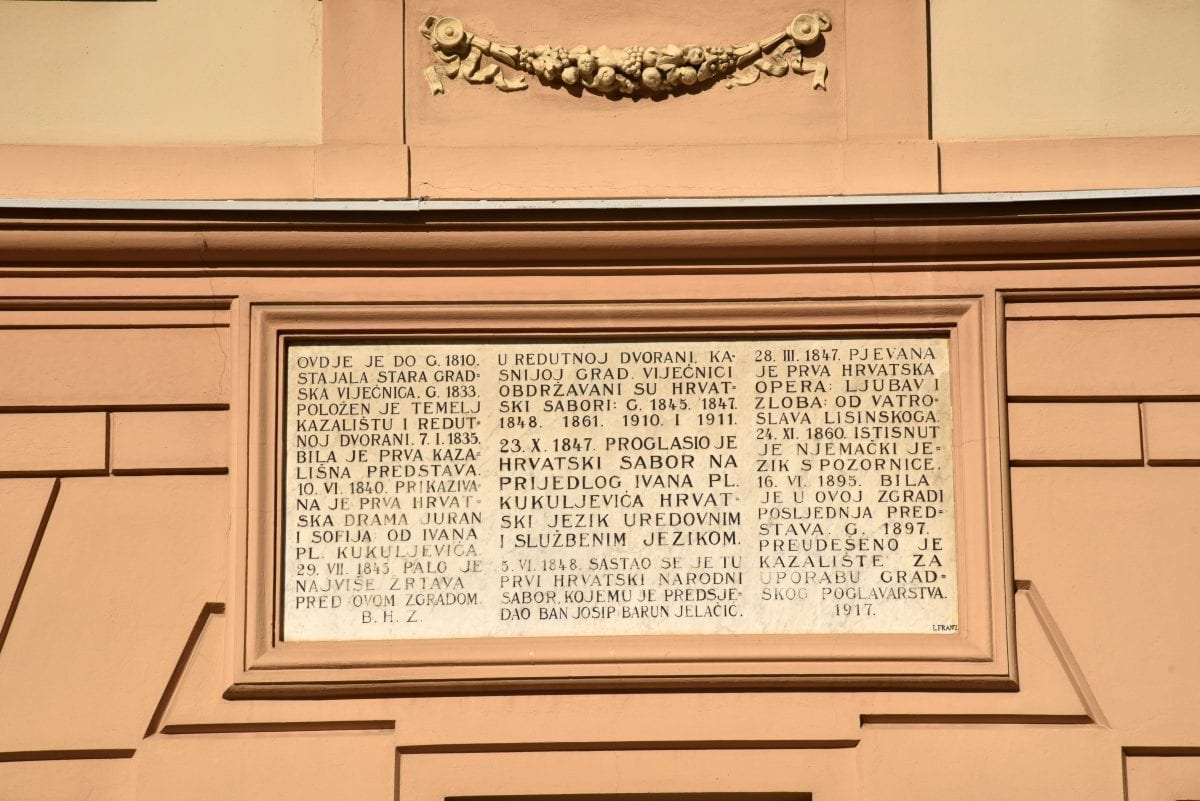

In 1834 Stanković built the first real theatre and, according to Medaković, truly “confirmed his reputation through his gift to the city”. These thirty thousand Kronen necessary for the construction did not come from Stanković’s personal profits as merchant or broker since he was in everything the opposite of what we would today call a “controversial entrepreneur” or tycoon. As it happens, he had won the main prize in the Viennese lottery. This first national theatre in Zagreb – for Stanković was an ardent supporter of the Illyrian movement – was built in Upper Town, and today this building houses the Zagreb City Assembly.

A room on the ground floor is today a Hristofor Stanković memorial room. As a fervent proponent of Slavic unification, Stanković used “siječanj”, “veljača” and so on as the names of the months, wishing to speak the “national language”, while the Zagreb press wrote of him as of a “very worthy patriot”.

At the grand opening of the theatre on 4 October 1834 a play was performed, and although it was in German, the theme was domestic: Zrinski under Siget. The first play in the national language was Juran and Sofija or Turks near Sisak, “a heroic play in three acts” with actors borrowed from Novi Sad since Zagreb had not yet formed a permanent theatre company. Ivan Mažuranić composed the prologue for the play, in which he wrote that it is “the seed the sweet fruits of which our grandchildren may one day enjoy”.

The Unifying Power of Theatre

The “Stanković theatre” in Upper Town was designed by architect Antun Cragnolini from Zagreb in the classicist-Biedermeier style, in the spirit of the time. Along with an auditorium with 750 seats in the stalls and galleries, the stage and backstage rooms, there was an inner courtyard, a barber shop and a patisserie on the ground floor and a dance hall with a gallery on the first floor. When the theatre became somewhat more established, the owner Hristofor Stanković gave it to the city, and in 1861 the Parliament decided that “the Parliament of the triune Kingdom of Croatia, Dalmatia and Slovenia takes the Yugoslavian theatre under its protection as public property”. Can today’s Balkan nationalists on all sides imagine that in the mid-nineteenth century in Zagreb the central legislative body, the Croatian Parliament, called the first national theatre “Yugoslavian” and admired its owner, a Serb, as a “worthy patriot”?

Like any other theatre, the Stanković theatre had its ups and downs and difficulties with the repertoire, but it also had splendid plays, its supporters and detractors. Like today, the social and political life of Zagreb at that time was multifaceted: there were sympathizers of Austria and Hungary, people’s tribunes and conservatives, but the Illyrianists – Hristofor Stanković among them – were the unifying force of the desired pan-Slavic brotherhood, and they saw this theatre in Upper Town as their cultural, political and national temple.

For National Pride and Self-Awareness

For Hristofor Stanković, the theatre did not represent the usual moral institution for the few aristocrats of the time; rather, for him the theatre was “one of the main preconditions for the development of the national pride and self-awareness, which we now mostly need”. For the rest of his life Stanković remained a great benefactor in his community through his various donations, making him perhaps a typical but important hero of his age. He was a representative of the successful liberal citizenry, a Serb who worked for the good of his close milieu and of the wider community – the city of Zagreb and its inhabitants, Croats, Serbs and everyone else. Influential in the political and economic sphere, Stanković moved in the circles of ban Josip Jelačić and the Ban’s Council, as well as the circles of the Zagreb Orthodox Parish and patriarch Josif Rajačić. Noted is his key role in the negotiations concerning Serbia’s loan to Croatia for the settling of war expenses in the tumultuous year of 1848, when Croatia defended itself against Hungary’s military pressure. Moreover, another participant in these negotiations in Sremski Karlovci, which concerned loans from the Serbian National Funds, was the president of the First Croatian Savings Bank Anastas Popović, also a Serb. We point this out because at that time philanthropy was a respected deed and an expression of selfless contribution to the common cause. Both Croats and Serbs left endowments in Zagreb and Croatia, and Stanković’s national theatre was supported financially by Ljudevit Gaj, Dimitrije Demeter, ban Josip Jelačić and many others. When in 1841 funds were being raised for the theatre, one of the first donators was the bishop of the Karlovac area Evgenije Jovanović, who contributed 25 forints, followed by Serbian officers from the ban’s and the Ogulin regiment, some of whom pledged regular donations from their monthly salaries in the amount of 10 to 20 kreuzer. Such selfless actions and a sense of belonging to the community were not isolated incidents: Jelačić’s minister was the economic expert Mojsije Baltić; the advocate for the unification of Croatian regions was the distinguished lawyer and minister Maksimilijan Prica; Ognjeslav Utješenović Ostrožinski was an Illyrianist and Varaždin County prefect, as well as an author in Croatian ethnography important to this day; Đorđe Ćelap was an important Zagreb book publisher; and there were many others sharing the same mission. A hundred years before the politically licensed brotherhood and unity in socialist Yugoslavia, there existed a unity and a harmony between Croats and Serbs that, in spite of occasional problems and opposition, really functioned. When the acting troupe of Stanković’s theatre toured Belgrade for two months, Danica Ilirska in Zagreb wrote: “Croats in a Serbian theatre perform a play for Serbs: is that not proof that Croats and Serbs are sons of the same mother Illyria, that both suckled the same Slavo-Illyrian milk? Is that not clear proof that Croats and Serbs speak the same language? This erases the harmful prejudices that have troubled our peaceful people; it erases the vain and senseless distrust that has torn apart our national concord.”

Time of Enthusiasm and Hope

Serbs in Zagreb in the nineteenth century, to whom Hristofor Stanković belonged, cannot be understood without understanding their close ties to the Croatian majority and to other citizens of Zagreb and their enthusiasm for national concord, nor can their existence be explained without their almost naive altruism, their desire to help and build. As Dejan Medaković concludes: “During the nineteenth century Serbs became part of all aspects of city life, achieving a good reputation and an honourable place in the process of the fast urbanization of this city.” We should also mention that the life of the author of the book Serbs in Zagreb is a part of this story: Dejan Medaković was born in Zagreb and spent his youth, the years up to 1941, in this city, later becoming a brilliant art historian. The fate of his grandfather Bogdan Medaković, a Viennese student and distinguished lawyer, is even more representative: in his house on Tomislav’s Square German was spoken at least half the day, like in a play by Krleža, but on the other hand, Medaković, as a supporter of the Croat-Serb Coalition, was president of the Croatian Parliament from 1906 to 1918. Even with all the political and national issues, it was a time of enthusiasm and hope – as much for Croats, who wanted their national freedom and separation from Austria-Hungary, as for Serbs, who, living in the same land for centuries, wanted the same.

Today, a hundred and seventy years later, the building of the Zagreb City Assembly in Upper Town testifies to the noble efforts of Hristofor Stanković to build a theatre and gift it to the city; other representative city buildings, endowments of Serbs who gifted them to the city where they lived, testify to the same. What is sadly gone are the descendants of these Serbian citizens of Zagreb, who were scattered far and wide from Zagreb and Croatia by the icy wind of national hatred. One of those who left was Dejan Medaković, and his book Serbs in Zagreb, which describes the importance of the work of Hristofor Stanković and so many others, ends with the words: “I dedicate this book to those who lost their homeland.”

Translation from Croatian: Jelena Šimpraga