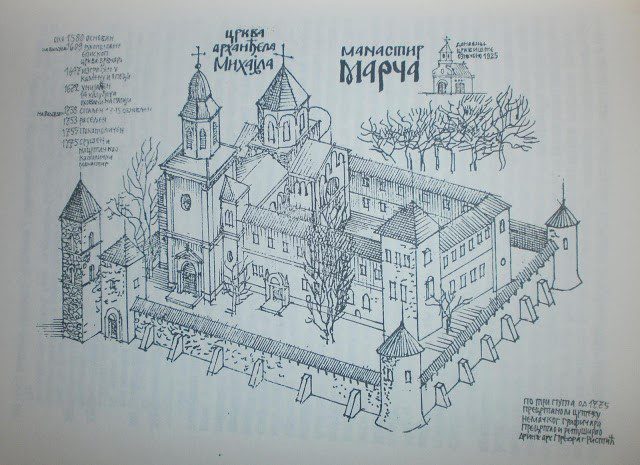

In the small village of Stara Marča in the Kloštar Ivanić municipality, between Čazma and Ivanić Grad in Croatia, an Orthodox chapel built in 1925 stands today. It stands in the same spot where the magnificent Orthodox Marča Monastery stood until 1739. Today, Stara Marča is a peaceful place that hides a history of ancient conflict, political games and intrigues, but also of unwavering faith and the struggle to preserve identity, even at the cost of survival. Even today, people of all faiths gather around this chapel every last Saturday in July, on the Feast Day of Saint Michael the Archangel. There is also a Greek Catholic chapel nearby, another sign of a turbulent past, only seen from a different perspective.

War for territory, but also for religion

Coming to Stara Marča today, a visitor can hardly see any traces of the turbulent events that took place here until the end of the 18th century. It all started in 1611, when it was decided that the first Greek Catholic monastery in this area would be built here. In the early modern period, when the Military Frontier was formed, the area in and around Marča was one of the deserted areas that would be populated by Serbs coming from the Ottoman Empire. The Military Frontier with its inhabitants was, in many ways, a special region of the Habsburg Monarchy, and resolving the status of those inhabitants was one of the main issues at the time. It made the Military Frontier the stage for political as well as military struggles within the Habsburg Monarchy.

With the Orthodox settlers of the Military Frontier came the Orthodox clergy, the bearers of the religious and cultural life. This helped the settlers preserve their identity in their new home. This separate identity was defined and affirmed in the Statuta Valachorum, the “Vlach Statutes”, in 1630. This statute gave the inhabitants of the captaincies of Ivanec, Koprivnica and Križevci a privileged position and defined duties (the right to elect a knez, i.e. the local ruler, and a grand judge, freedom of trade, borders of villages and districts, etc.). In return, they guarded the monarchy’s border and fought in its wars. The great importance of the clergy for the frontiersmen is evident from the fact that the state authorities appointed the Orthodox bishops (episkopi) based on the proposals of and in coordination with the representatives of the people of the Military Frontier since the mid-16th century.

Resistance to unification with the Catholic Church

The Military Frontier was part of Croatia, but was under the command of the War Council in Graz and therefore exempt from the jurisdiction of the Croatian ban and the Croatian Parliament. Religion was generally an important factor in Europe of the early modern period. The religious mosaic of the Habsburg Monarchy was the cause of various divisions and wars, the bloodiest example being the Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648), when the religious (and political) conflict between the Protestants and Catholics escalated into a war. It is therefore unsurprising that attempts against their religion and, consequently, status provoked resistance and unrest among the Orthodox population.

The Marča Episcopate was established in 1611 with the goal of inducing the Orthodox population to accept the Greek Catholic rite and the pope as the supreme religious leader. The local population did not meet this with enthusiasm. Even before the episcopate was established, the Orthodox clergy got in contact with the commanders of the frontiersmen in order to organize religious life in the areas they inhabited. The idea of Uniates was completely new to the settlers and their clergy; it was perceived as a threat, mostly because of the possibility of the loss of privileges, but also of identity, of which religion is an important component. Greek Catholicism, which formed at the end of the 15th and grew stronger during the 16th century, was in theory more acceptable to the settlers than Catholicism because of the rite they were familiar with. The connectedness of the population with the Orthodox clergy played a crucial role which prevented the Uniate efforts from achieving the desired result. Because of this, it is important to emphasize that the clergy and religion had not only a religious, but also an ethnic, i.e., status role, which resulted in Greek Catholicism largely being rejected in Marča.

Simeon of “Vretanija” – between the people and the state

The idea of the state authorities to make Marča the seat of Greek Catholicism began with the coming to this area of Orthodox monks, led by vladika (bishop) Simeon of Vretanija at the beginning of the 17th century. They fled the Ottoman rule and founded the monastery and church of Saint Michael the Archangel in Marča. The Zagreb bishop, Petar Domitrović, himself a descendant of Orthodox refugees, gave the church estate in Marča to Bishop Simeon in 1611 and made him the archimandrite of the monastery. Simeon’s appointment as the archimandrite of the monastery symbolized the conflict between several sides: the pope, the emperor and the Patriarchate of Peć (which gave him the epithet “of Vretanija”, i.e., “of Britain” as the furthest region of Orthodox Christianity in the west). After his appointment, Simeon went to Rome, to Pope Paul V, who recognized him as “the true bishop of the Rascians of the Greek rite.” The emperor had already given him authority over the settlers who belonged to the Eastern rite.

For the Orthodox population to accept the pope as the head of the church, the role of Simeon and his successors was to mediate between the Orthodox population and the state. Bishop Simeon had to personally negotiate the unification with the Catholic Church with the captains and the monks. The balancing between the wishes of powerful political and religious centers did the most harm to the people, who were not ready to renounce their faith and endanger their status. The first half and a part of the second half of the 17th century in Marča were a period of unsuccessful promulgation of uniatism among the Orthodox population. It could hardly have been successful since the “blessing” of the frontiersmen and their commanders was necessary for the appointment of the bishops to be accepted. An unsuccessful appointment was also a sign of the inability of the Croatian nobility and the Zagreb bishop to bring the area and the people of the Military Frontier back under their jurisdiction. It seems that these pressures had, in fact, the opposite effect. The influence of the monks from the Patriarchate of Peć grew stronger, and Marča increasingly became the center around which the local population gathered.

The idea of the Zagreb bishops, such as Petar Petretić, was for the bishop of Marča to be their vicar for Christians of the Eastern rite in the Zagreb archdiocese and not a coequal ruler. Petretić, for example, also supported the interests of the nobility and therefore came into conflict with the commanders of the Military Frontier, who strongly resisted the possibility to renounce their privileges and become serfs. One of the bishops who illustrates the political as well as religious importance of Marča was Gabrijel Mijakić (1663-1670), who is known to have been connected with the Zrinski-Frankopan conspiracy. It is worth pointing out that Petar Zrinski and Fran Krsto Frankopan were accused of attempting to give privileges to Mijakić and his congregation. The failure of the conspiracy enabled the emperor to crush the power of the nobility and strengthen centralism and absolutism, which also helped appoint a Greek Catholic bishop in Marča, who was supposed to conduct the unification with Rome. That is why the choice and function of the bishop were not only a religious, but also a political and military matter.

Frontiersmen under the bishop

After the failure of the conspiracy, Pavao Zorčić (1671-1685) became the new bishop of Marča. He accepted the role of the vicar of the Zagreb archbishop and renounced the Peć patriarch. This helped the strengthening of uniatism in that period, as well as unrest among the population. The introduction into his office of Bishop Zorčić was first held in Križevci, and then in Varaždin in 1678 because of the discontentment of the people. The arrival of the bishop affirmed by Pope Clement X and the Ukrainian Uniate Bishop Kolenda without an approval from Peć evidently caused disappointment, which General Herberstein had to pacify. With Zorčić began the period of conflict between the monks of Marča and the appointed bishops. Uniatism was conducted most intensely during the time of Bishop Zorčić.

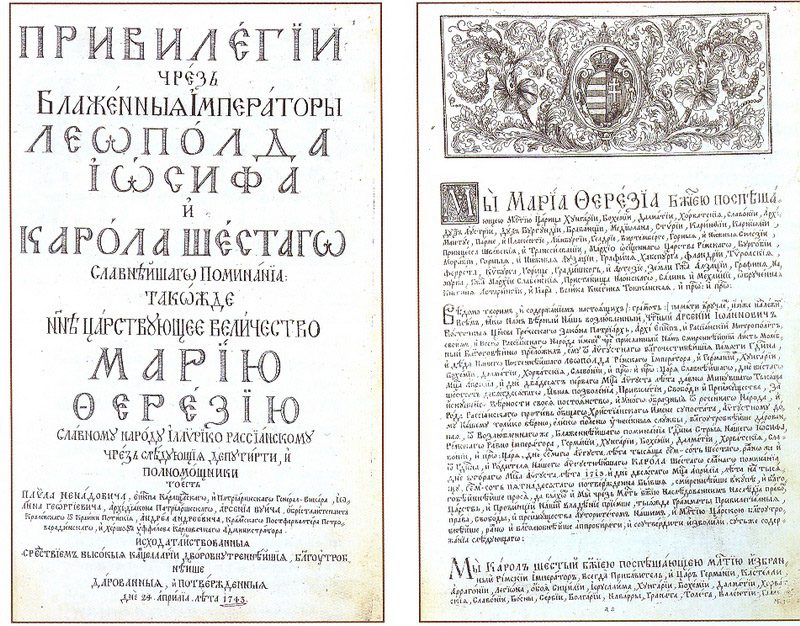

With the arrival of Patriarch Arsenije Crnojević and a great number of Serbian refugees in the Habsburg Monarchy, the patriarch obtained an imperial charter with great privileges from Leopold I at the end of the 17th century. This brought great changes to the Orthodox Church within the Habsburg Monarchy, and the Severin-Lepavina Eparchy was founded as part of the Karlovac Eparchy. From then on, many Greek Catholic centers became Orthodox, and in 1735 Marča was among these for a while. Poor relations between the monks of Lepavina and the bishop of Marča continued until the destruction of the monastery in 1739. This year marked the escalation of the dissatisfaction with a series of decisions and the attempts of conversion to the new faith. After the decision that Marča would belong to the Greek Catholics, the final conflict erupted. The Orthodox population and the monks decided to burn the monastery rather than give it over to the Uniates. After unceasing conflicts that lasted more than a hundred years, in the end Marča was destroyed and disappeared.

Marča formally existed after 1739; in 1755, it was given to the Piarist order, who established a school in it. Its political and religious relevance then ended, the conflicts disappeared, and an estate was all that was left of it. Greek Catholics founded a new seat in 1777 in Križevci, and the Orthodox population found their religious center in the Lepavina Monastery. After the Piarists, Marča became the property of the Lončar family, who gave a part of this property to the Orthodox parish in Lipovčani.

The Marča Monastery was thus destroyed physically and symbolically, as was the Uniate idea. With the disappearance of political interests, the unrest in Marča also soon disappeared. Uniatism in the territory of the Orthodox people of the Military Frontier was little likely to succeed because the desire for church unity was very weak.

As much as he depended on the church and state authorities, in the end, the bishop of Marča depended on the people of the Military Frontier the most, the people whose privileges he was supposed to preserve, as the people did him.

Today, Marča is far from any political interests or conflicts. One person of Orthodox faith officially lives in Marča today, and some twenty live in nearby Lipovčani. The area is economically undeveloped, and, instead of the many conflicts of once-clashing faiths, people of all faiths now gather in peace every year at the service in front of the Orthodox chapel built in 1925.

Translation from Croatian: Jelena Šimpraga