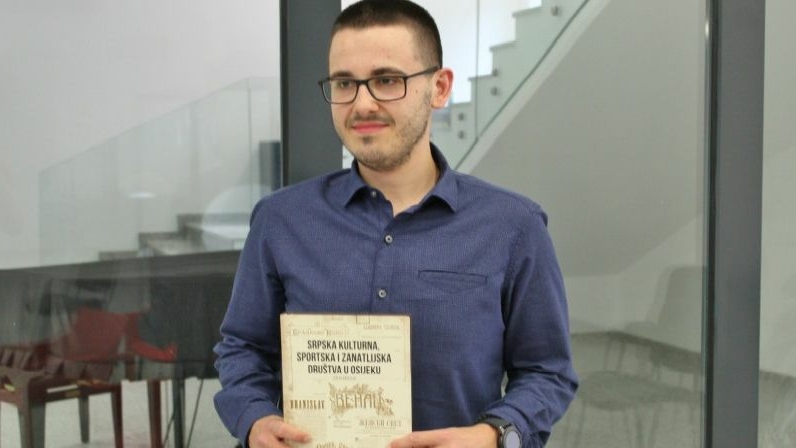

Zoran Mišković, a young doctor from Osijek, spent six years researching the cultural heritage of Serbs in Osijek. The results of his interest, unusual for young people, are published in the book Serbian Cultural, Sports and Craft Societies in Osijek. Despite his attachment to the city and the years dedicated to the research, Zoran moved from Osijek to Varaždin. Asked why he decided to move, he admits he wanted to free himself of the old environment. “I think Osijek still has its taboos and limitations. Varaždin is a place that seemed more open. I think that a person needs to hear about innovations, especially in medicine. The fact is that the gravitation towards Zagreb brings advancement in the profession,” Zoran explains. We asked him to present to us the most important results of the research, but also to tell us his thoughts on some important questions of identity.

What are the limitations you felt in Osijek? What encumbered you there?

I think it is an environment where wounds are still very much felt, and understandably so. What is talked about little is how it is to be stigmatized from an early age. It produces perhaps not fear, but a kind of unease. None of us chooses our place of birth. If we did, we would surely be born in Switzerland and not the Balkans. Today, at 29 years of age, I can only imagine what my mom went through when she had to explain to me why someone didn’t want to spend time with me just because of my surname. It was very freeing for me when I went to college in Novi Sad. I didn’t fit in with the majority there because the problems in society, very similar to ours, bothered me. In Novi Sad, I socialized much more with Croats of Vojvodina, whose problems were similar to mine. I understood them much better.

Can you tell us something about how your family lived through the war years in Osijek?

Dad was fired from his job at the health center in 1991 without an explanation and started working again only in 1996 and not in the field he specialized in. Mom worked in the textile industry in Slavonia throughout the war but afterwards could never find work again. My father didn’t want to leave; he wanted to change things. Unfortunately, there was very little he could do. I am afraid his health would have been much better had he gone somewhere else. Maybe he wouldn’t have had to survive six strokes as a result of all the stress. We survived that time only thanks to friendships with some people who didn’t follow the general social climate at the time.

Childhood burdened by stigma

How do you explain to yourself this permanent position of a stranger, outsider, someone “not from around here”? How do you deal with that? Did your perception change as you grew up?

It changed because now, as an adult, I can understand that somebody’s behavior towards me is motivated by their feelings, their negative experiences. Then I can forgive, not take it personally. But I didn’t understand that then. It was very hard for me to grow up in a place where I was called an alien, where people said I didn’t have the right to be there. That is why I was interested in history, as were my father and grandfather. They did research all the time, from before the war, about the close ties between our communities, the Croatian and the Serbian. My grandfather was a parish priest in Osijek. He came from Čepin to Osijek after the Second World War, when the church was destroyed and the community afflicted, and started collecting and working on the data on the history of the Serbian community in Osijek. On the other hand, in that crucial period when tragedy was unfolding in our region, dad wanted to offer an alternative. We share people who depended on each other throughout history. My book starts with the history of the Serbian Reading Room in Lower Town. The reading room was founded in the time of the revolution in 1848, during that first revolt and effort to defend ourselves together – the Serbian and Croatian community against Germanization and Magyarization. I see the crucial moment in its work in the moment when 43% of Osijek citizens declared their mother language was Croatian or Serbian, while 49% declared it was German. Therefore, the unity of Croats and Serbs played a key role in the fight against the Germanization of both nations. Lower Town Croats became members of the Serbian Reading Room already in 1868. The reading room allowed members of other ethnic communities to join. It was founded to promote the spirit of education and culture and is among the first such Slavic institutions. It was especially a meeting place of Lower Town Croats who followed the Illyrian ideas of Ljudevit Gaj, Bishop Josip Juraj Strossmayer, Lazar Bojić and Lazar Popović.

Why did you decide to collect information about the history of Serbian cultural, sports and craft societies in Osijek?

I didn’t grow up with stories about famous footballers. I grew up with stories about Bishop Strossmayer and his friends from our community. In fact, I came cross a badge of the Gusle Serbian Singing Society, the oldest such society, founded 170 years ago. There are no records or research about this society. I wanted to show and prove that we Serbs have firm roots in Osijek, that we built it together with all the other communities. I wanted to document that so that it may serve generations after mine. For example, at the turn of the 20th century, togetherness prevailed to prevent the Germanization of both our ethnic communities in Osijek. The deciding vote for the building of the Osijek cathedral was cast by Orthodox priest Lazar Popović.

What is, for you, the most valuable discovery you made while researching for the book?

Finding a record about gusle is one of the most important events in my life. It is a record from the 19th century, the only evidence with the original seal and list of members that wasn’t destroyed in the period of the Independent State of Croatia, when churches and archives were destroyed and priests arrested. My grandfather Lazar was taken to jail and then to an internment camp. He went through four camps during the Second World War.

A book out of love for Osijek

Six years working on a book is a long period. What motivated you in the research process?

Although everyone says that Serbs in the Osijek area have a long and rich cultural and education history, the research took a long time because the archives of the societies and of the Serbian Orthodox Church in Osijek perished in wars, and what remained is scattered in libraries and archives throughout the area of the former Yugoslavia. But this book is first and foremost my love for Osijek. My second love is for the Serb community in Osijek, to which I wanted to show all that I found out. I am lucky to have grown up with a singer of the Gusle Singing Society, who taught me church singing. My grandfather Lazar also sang in that society, so this personal story acquires a wider context.

Who is your book intended for?

My generation. I think my growing up would have been much easier if I had had one. I think everyone, but us Serbs especially, need it to see that nothing is black-and-white and that we need to find ourselves in that greyness.

Can you tell us more about one of the more important Serbian cultural societies in Osijek that are still active?

The Serbian Women’s Charitable Society (“Srpska ženska dobrotvorna zadruga”) is the only original Osijek society that is still active today under its original name. It was established in 1897 at the initiative of spouses Ana and Vaso Đurđević. Vaso Đurđević was a member of the Croatian Parliament from 1875 and its president in 1893 and 1899. The society was founded to help poor citizens, primarily children. It established the celebration of “Svetosavske besjede” (a cultural event in honor of Saint Sava) as a prime annual event of Osijek Serbs. Thanks to a select program and the performance of numerous solo artists, the event was visited by citizens of all ethnicities. The society’s work was prolific until the Second World War, and its members organized numerous charity parties and concerts in cooperation with many Croatian societies to raise aid for the needy. They are especially remembered for their help to Russian refugees after the October Revolution. The society was forcefully shut down in the Second World War, and in 1945 it lost the right to public work. From then until 1991, the society acted as a church charity organization as part of the Church Community.

If you led us on a tour of Osijek, what would be the places important for the Serb community that testify to its presence throughout history and now?

The key places for the Serb community are in Upper Town, at the place of the former school of hospitality and at the Maksimović house, which Patriarch Branković built for his daughter when she was getting married. The Jelisaveta Vukašinović Church Endowment, a house that the owner left to the Church, is at the main square. Jelisaveta Vukašinović’s endowment was established to fund charity work, build a Serbian Orthodox church in Upper Town, an Orthodox chapel at Ana’s Cemetery and provide scholarships to pupils and university students. She also helped establish the Upper Town Serbian Elementary School. I especially want to mention the Cross of the Vow in Lower Town, a monument that is a part of our cultural heritage, at which Ban Josip Jelačić made a speech in the 19th century, while our chapel at the cemetery from the 19th century is preserved in its original form.

In your opinion, how important is it for a person to know and learn from their own history in order to understand what constitutes national and religious identity?

The cult of tradition is very present in our people. We all grow up with the story of the great migration in the 16th century, when we came to this part of eastern Slavonia. From an early age, you are brought up with the idea that it is important to preserve your family and roots, that it is something that cannot be forgotten. Even though we have roots in the southern Balkans, our other roots are in Osijek. It seems to me that we have lost the foundation of our community and that we must build a new one. History, which tells us who we are and what our worth is, offers us answers that the next generation should also have. Today’s generation of people in their sixties and seventies is not the future. I think people of my generation and younger ones should get answers about their origins and identity through something like this book. Then, perhaps, this mimicry and fear that still exist in us Serbs will not be so prominent.

Translation from Croatian: Jelena Šimpraga

This post is also available in: Hrvatski