It is old news that buildings, walls, monuments and many other places in public areas of Croatian cities are covered in offensive, hateful and chauvinistic messages. However, lately more and more individuals and initiatives have appeared who want to put a stop to this.

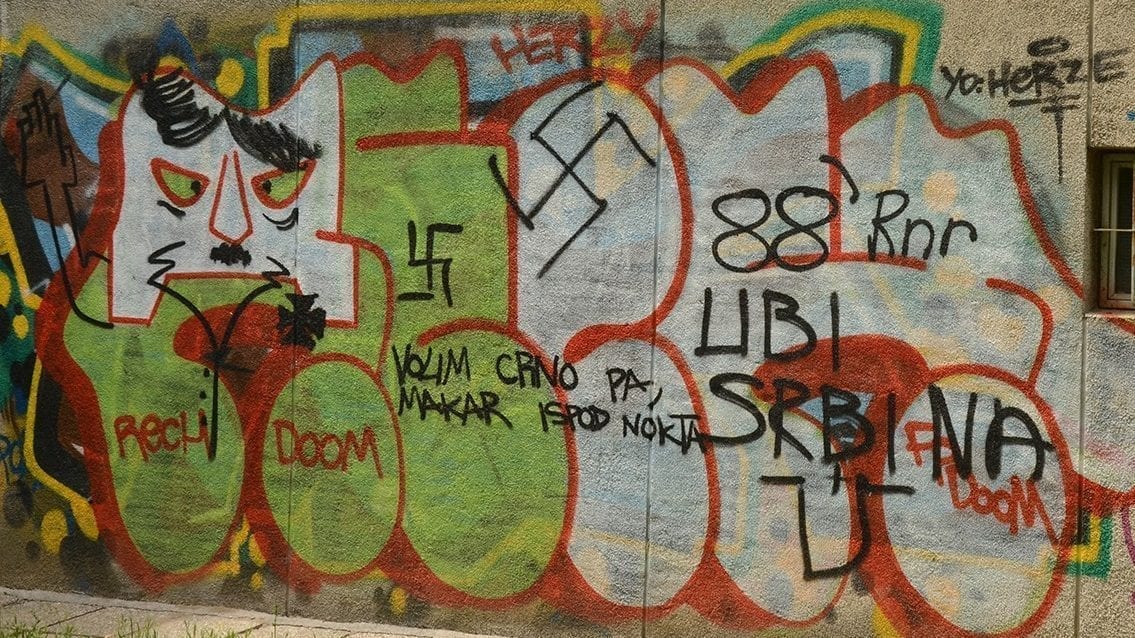

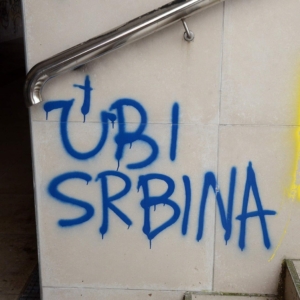

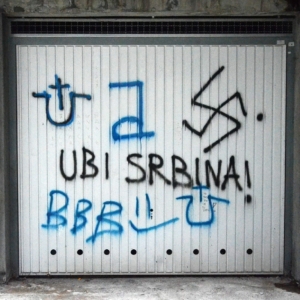

“One writing is an incident; a hundred writings are the state of society”, artist Tanja Dabo and curator Davorka Perić tell us. Together they are working on the project “Evil along the Way”, whose initial goal was to record the state and the attitude of society towards writings in the public space containing fascist, Nazi and Ustasha symbols, messages of hate and calls to killing of those different.

“We started this research art project a year ago, but we have both been thinking about this topic for a while now”, Dabo and Perić tell P-portal. In the first phase of the project they inquired of the relevant institutions about the legal framework which permits or prohibits these symbols and messages. “Unfortunately, we did not get the information we were interested in”, they say.

While conducting the project, they realized that “not only is it impossible to document all the writings – something we were aware of from the beginning – but we also had to limit our activities to just mapping the locations, and even so we could not document them all”. They carried out their research in three larger cities – Zagreb, Osijek and Split – and in smaller places and other micro-locations across Croatia.

Dabo and Perić have documented and processed more than 400 writings containing hate speech and symbols at around 170 locations

Once the project is completed, their intention is to report all the writings they found by submitting the exact addresses and photographs and then request of the authorities to remove them. Having documented and processed more than 400 writings containing hate speech and symbols at around 170 locations at this moment, they have just entered that phase.

“We are interested professionally and as citizens to see what their response will be”, they tell us. They also included other citizens in the project, who send them photographs and locations of the writings. In the beginning there was very little response from citizens, they say, but gradually the response grew, which encourages and motivates them to continue documenting and processing the writings even after the project is formally finished.

“The citizens do care, but there are many reasons that prevent them from acting, and one of them is fear. Most people who submitted information also requested to remain anonymous or said that they were afraid, meaning that we should be extremely cautious when going to the location they told us about”, Dabo and Perić explain.

“New writings appear daily, and this fight cannot be won this way. Institutions should join the fight, but also all citizens who believe that this kind of content has no place in the public space, and we take this opportunity to invite them to join the fight”, the researchers told us.

An increasing number of recorded instances

Hate speech in the public space is also noted in the annual reports of ombudswoman Lora Vidović. Although Vidović noted in her report for 2019 that “there has been progress in countering the rise of historical revisionism”, she added that the symbols of Ustasha and Nazi ideology are still present in internet posts, graffiti, flags, clothes and other places.

The Serb National Council, which publishes the report “Historical revisionism, hate speech and violence against Serbs” every year, notes the examples of graffiti and symbols containing hate speech and ethnic intolerance on public surfaces. According to this report, last year there were 40 such examples, the most ever, the year before that there were 33, and there were 35, 26, 14 and 8 instances in 2017, 2016, 2015 and 2014, respectively.

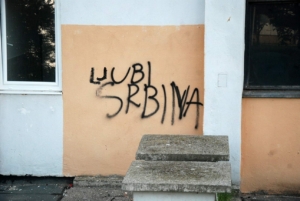

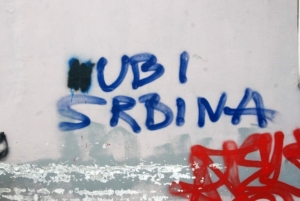

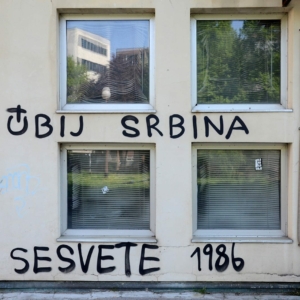

“Facades in Croatian cities and other populated areas are full of graffiti that glorify the Ustasha and Nazi regimes and promote hatred against Serbs”, SNV stated in the report, adding that “they now increasingly appear as direct threats, i.e. as writings on private property of Serbs, such as in the example in early December when Ustasha graffiti appeared on the house of a Serb in Našice.”

SNV pointed out in its report that “one type of inappropriate graffiti and messages is the use of the word ‘Serb’ or ‘Serbs’ as an insult for a particular social group or profession considered an enemy for some reason, such as in ‘Journalists – Serbs’”.

No place without them

Photographer Jovica Drobnjak has come to similar conclusions, having documented thousands of graffiti with inappropriate content with his camera, although graffiti are not the only subject of his work and interest. Two years ago, Drobnjak had a photography exhibition titled “Boje i lakovi” (“Paints and Varnishes”) whose theme was the controversial former football manager Zdravko Mamić, i.e. street writings about him.

Most of these graffiti are clear examples of hate speech, not only towards Mamić, but also towards the minorities who he is identified with in order to insult him as much as possible. The most common examples of these insults are “Mamić, Serb”, “Mamić, Gypsy”, “Mamić, Turk”, “Mamić, fag”, etc.

“This is certainly a sign of a society of intolerance towards anything that is different”, Drobnjak tells us.

Last year in November, on the International Day for Tolerance, Drobnjak opened another exhibition dedicated to graffiti in Zagreb, titled “Walls of Hate”. He tells us that “there really are no public surfaces spared from them”, from walls, kiosks, traffic signs and underpasses to tram stops and trash cans. “They are absolutely everywhere”, he says, adding that they are very rarely removed, at least as far as Zagreb is concerned. It especially bothers him that symbols such as the swastika are still found in children’s playgrounds.

“What bothers me is that these children, who play there every day, unconsciously absorb these symbols as something ‘normal’ because they see them every day”, he explains. For him the best solution is the complete removal of such content and not “drawing and scribbling over it”.

Signs of civic courage

Our next interviewee, Ivan Zidarević from the European Citizens’ Initiative Zagreb, regularly reports graffiti with inappropriate content to the authorities and is satisfied with their reactions.

“All institutions, and especially the police, immediately respond to submitted reports”, Zidarević claims, also adding that his reports are written in Serbian. Regardless of that, he tells us that the institutions “always send a notification that officers were sent to the scene and made a report”.

“So far all local authorities have removed any graffiti screaming messages of intolerance or hate or inciting hate crimes”, he continues.

In the last three years, the European Citizens’ Initiative Zagreb reported some thirty graffiti from all parts of Croatia. Zidarević says that last year saw the greatest number of reports. He himself noticed some of the graffiti and reported them, and other citizens informed him of around a third of them, which indirectly makes them “heroes of the street” as well.

“This is important work that few know how to do right. Unfortunately, many citizens do not know how to write a report, which, justifiably or not, should not be written in an emotional tone. It should be concrete, specific, formal and express trust in the institutions to which it is addressed”, he states.

“In addition to being an act of vandalism, usually without any artistic value, each of the inappropriate graffiti contains elements of a felony”, he answers in response to our question why it is important to be persistent and report cases like these.

“The duty of citizens is to act and report that which at its core aims to create anxiety in others, in our case in those who are nominally or seemingly different. We live in a society of growing individualism and I see this issue as the result of a lack of empathy”, he explains and adds that “we should show some signs of civic courage and perseverance because nothing is a given and nothing should be taken for granted”.

Revolt should be channelled into something productive

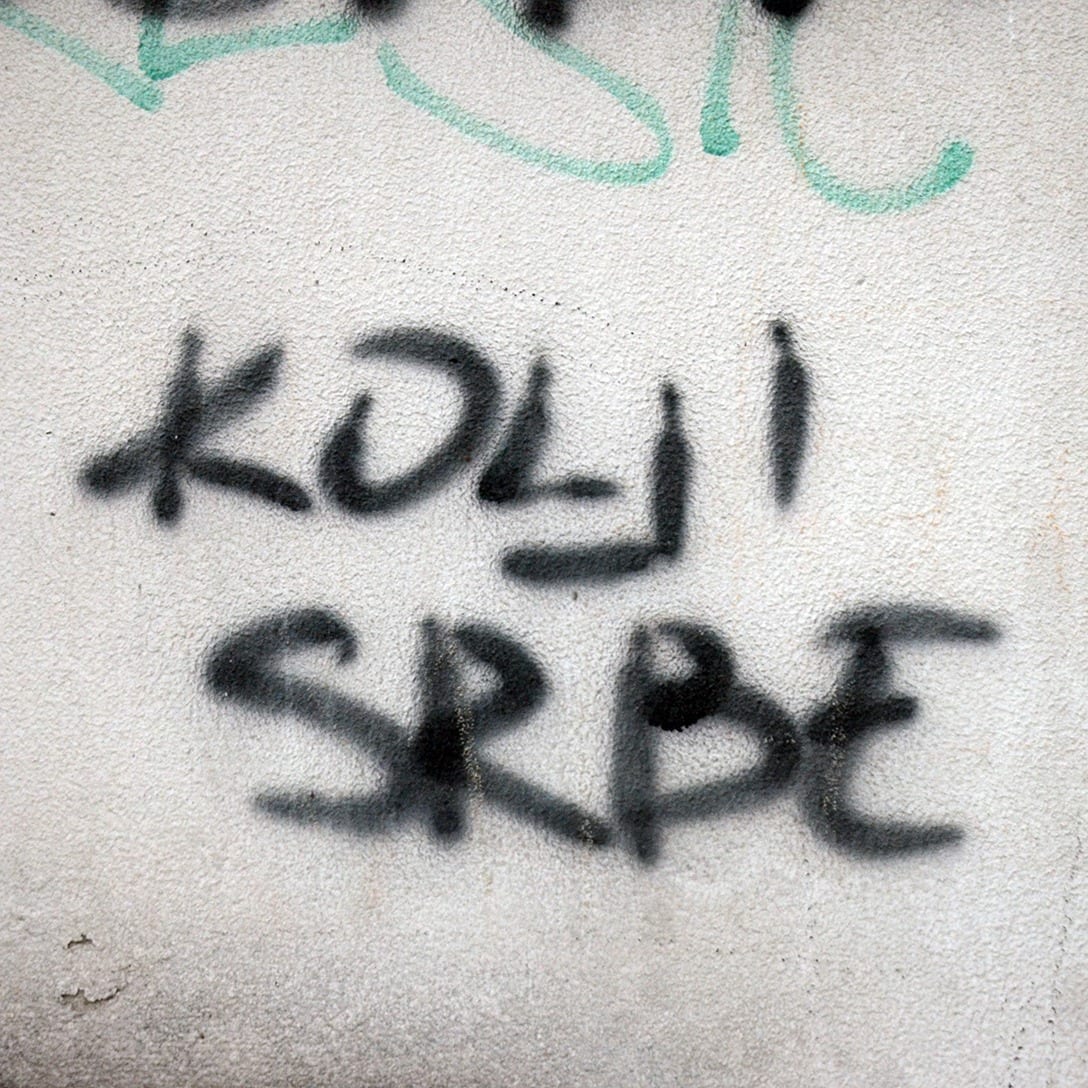

One specific kind of civic courage was shown by Jure Zubčić, a young city councillor from Zadar, who could not simply pass by the hate graffiti in his city and therefore turned a message of hate into a message of love with one simple intervention.

He became known to the Croatian and regional public after he altered the graffiti “Kill the Serb” to spell “Kiss the Serb” last year. Motivated by his action, the EXIT Foundation from Novi Sad started a regional campaign called #ShareLove, inviting people from the region to share similar positive messages and examples on social networks.

Zubčić became known to the Croatian and regional public after he altered the graffiti “Kill the Serb” to spell “Kiss the Serb” last year

On the other side of the country, in Osijek, the newly-founded initiative Mladforma works with a similar goal, turning graffiti with inappropriate content into creative street paintings.

Nikica Torbica, one of the founders of Mladforma, told us that they started these activities last summer, around Antifascist Struggle Day. That day was a good cause, he says, since there was a “scrawl” with Ustasha symbols on his sister’s house.

“We purposely do not call it ‘graffiti’, but ‘scrawls’”, Torbica explains, adding that Mladforma wants to send its fellow citizens the message “that such scrawls simply have no place in our city, and that there is one group that is determined to oppose them.”

Of course, painting over the “scrawls” and creating new, more cheerful graffiti costs money, but Torbica explains that they manage it with the financial help of the city.

“We did not want just a ‘guerrilla’ action, although we have nothing against ‘guerrilla’ actions; rather, we specifically wanted to show that you can change things through legitimate channels, through cooperation and dialogue with the decision makers. Therefore, the city helped us in this with funds for the graffiti”, Torbica explains.

Like our previous interviewees, he also concluded that the targets of this kind of hate speech are Serbs, Roma and LGBT people – actually the same groups, he says, that were the targets of the Ustasha regime. Torbica says that the perpetrators are mostly young people, but he emphasises that these phenomena are only symptoms of a general social climate.

“That is why Mladforma’s idea is to show young people that they can express their revolt in other ways and that this revolt does not have to be so negative”, he says and concludes: “If you feel revolt, that is fine, you should feel some revolt in you, but you have to know how to direct it in order to turn it into something productive for the society we live in.”

Translation from Croatian: Jelena Šimpraga

This post is also available in: Hrvatski