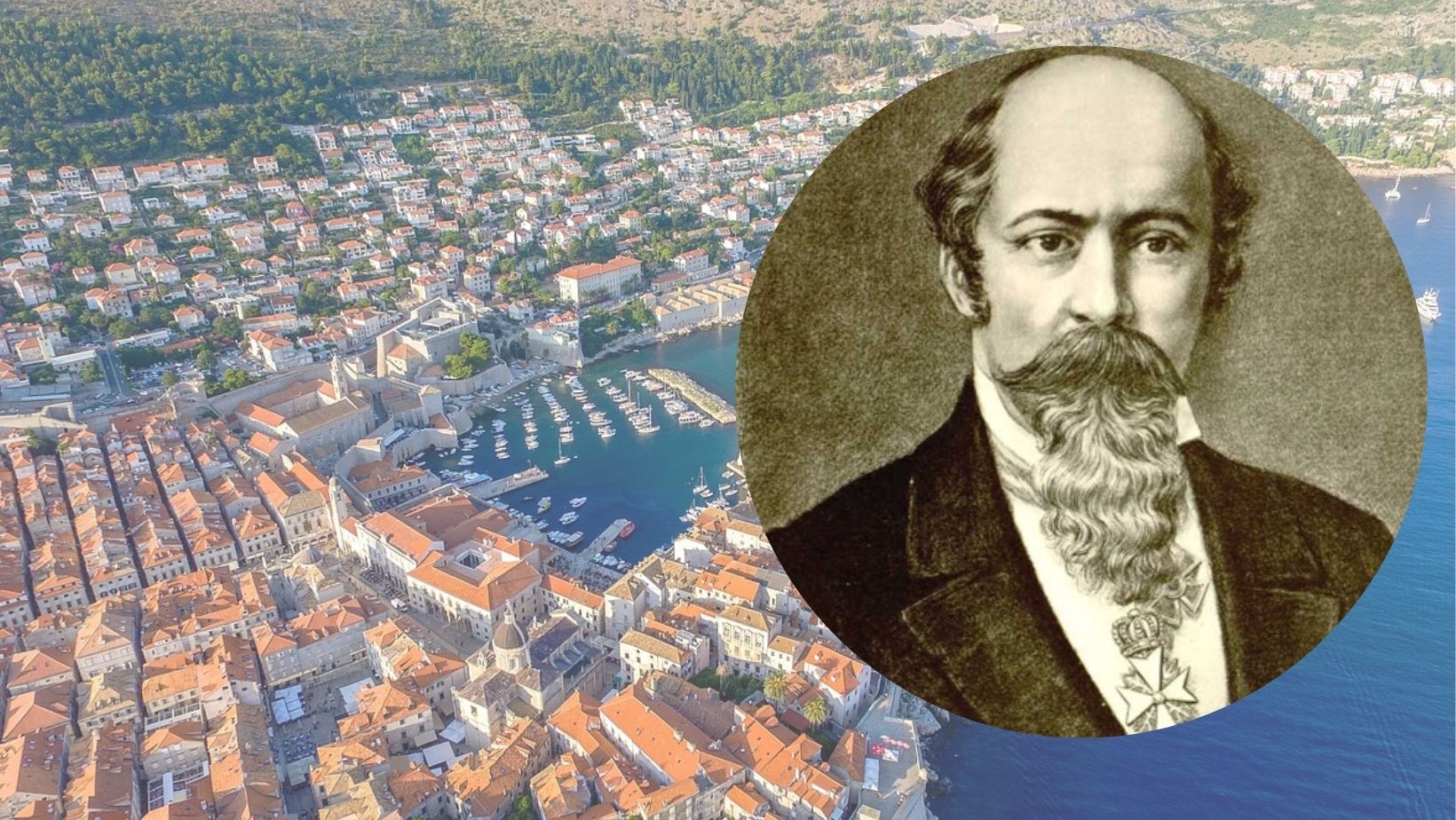

On this day, March 12, 1821 – precisely two centuries ago – writer, poet, scientist and politician Medo Pucić was born in Dubrovnik. He was a descendant of one of the oldest noble families of Dubrovnik, the family of Pucić, whose line goes back to the 13th century and who were awarded the title of counts (“count of the hinterland”) by Austria centuries later. As with other noblemen, when introducing himself in one of his books, his list of titles and awarded ranks is impressive: “nobleman of Dubrovnik, count of the hinterland, johannite knight, chamberlain to His Royal Majesty, the Spanish infant and Duke of Parma, member of the Roman Academy of Quirites and of the royal Viennese Society for the conservation of antiquities”. Elsewhere he is mentioned as a member of the “Sovereign Military Hospitaller Order of Saint John of Jerusalem”.

Like many others from his social class, he was educated at the lyceum in Venice, after which he studied philosophy and then graduated in law in Padua. He would remain professionally tied to Italy as the chamberlain of two of the greatest noble houses – first as the chamberlain to the Duke of Lucca and then as the chamberlain to the Duke of Parma. More importantly, Pucić is inseparable from Italy because he would write in and translate to Italian almost his whole life, signing his work with Orsatto Pozza, the old, customary Italianized version of his surname and the noble house of Pucić used through centuries. He was a scholar in history and left us two extremely important historiographic works. In this sense, he is a romantic, as were many young intellectuals of the period who came from “small” Slavic peoples experiencing national awakening and seeking emancipation within old empires. As a student of Jan Kollar, the main ideologist of the Slovak national revival, he was also a Pan-Slavic idealist, follower of Šafarik and a convinced “preacher of Slavic reciprocity”, just like the great but today less celebrated Kollar.

A scholar inspired by folk poetry about Kosovo

Like many young men of his generation, he also tried his hand at poetry in the popular ornate, emotionally charged romantic style. This was very much in line with the personal and cultural heritage of Pucić as an author from Dubrovnik, a city with an immense and unique literary tradition. It was also in line with his mother tongue, the dialect that had the status of the ideal and our “Tuscan” before Vuk’s reform. However, the future key influence on his aesthetics and ideas will lead Pucić to change his style and bring it closer to an expression characteristic of the people, the folk.

He started publishing poetry as a man classically educated in Latin, Greek, law, philosophy and history (the latter being an area of professional work for him), as a man of wide culture and as a child of romanticism and romantic literature. However, the main literary and cultural influence on his poetry came from a different, unexpected source: Serbian folk poetry, above all the so-called “Kosovo cycle”.

The change was not only aesthetical. It was preceded by a fundamental change in ideas, a combination of political and historical convictions that would over time become an astounding shift of identity. Prior to that, he went to Italy, where, despite deep personal, cultural and historical connections, he never felt at home, but always considered it a foreign country (which he would express in his poetry). When he returned to Dubrovnik after years of service in Italy, his path was already decided. In Dubrovnik, he and Matija Ban (after whom the Belgrade neighborhood of Banovo Brdo is named) were the founders and editors of the first literary magazine in the Croatian language. He wrote historiographical studies, studies in cultural history and, of course, poetry. However, whatever he was working on – and he was involved in politics, science and art, being one of the first to single out the talent of the young Vlaho Bukovac – this path led in only one direction.

The Belgrade period and educating the young king

In the fatal 1868, after the assassination of Prince Mihailo Obrenović in Košutnjak, Pucić came to Belgrade to be the private tutor of Prince Milan, then still a child, intended to be the heir to the dynasty while the famous Blaznavac regency ruled in his stead. Pucić remained in the Prince’s service until his maturity and coming-of-age. It would not be for nothing – the Prince would become the first king of the independent Serbia.

The significance of his time in Belgrade is shown in a sentence recorded by writer and encyclopedist Milan Đ. Milićević: “I began my career with the oldest dynasty in Europe and ended it with the youngest, the Obrenović dynasty.”

This suggestive sentence was published as part of Pucić’s biography in the very valuable Pomenik znamenitih ljudi u srpskog naroda novijega doba (a biographical lexicon of notable persons of the Serbian people) from 1888. The designation of “notable persons of the Serbian people” is worth noticing.

Literary historian Andra Gavrilović included Pucić in his book Prominent Serbs of the 19th Century, and the indispensable and meticulous Vladimir Ćorović mentions him much later in his History of the Serbian People, stating, in a typically unconventional sentence, that Medo Pucić was “an honest and well-intentioned but rather carefree man”.

How did a Dubrovnik nobleman with a double, Italianized name, a devout Catholic and count – although a member of the Serbian Learned Society and, naturally, the Yugoslav Academy of Sciences and Arts – end up among prominent Serbs? How did it happen?

A unique phenomenon of a unique City – “Serbs of the Roman law”

In the long and dramatic history of this region, at the turn of the 19th century there appeared a little talked-about and permanently ignored phenomenon kept from the wider public consciousness and the masses, a historical phenomenon approached to this day – and especially today – with extreme discomfort in this country. In Dubrovnik, a city which is a completely separate fact of Croatian, Serbian and Yugoslav history, a phenomenon sui generis in every regard and an indispensable constituent of national identity, there appeared in the 19th century a group that would grow into a whole movement. Recruited in large part from the highest social circles, from Dubrovnik nobility and elite, this unusual, complex and undoubtedly important phenomenon was – Dubrovnik Catholic Serbs, also named “Serbs of the Roman law”.

In the 19th century, the period of the release of great national energies in the Slavic South and all of Europe, full of subjugated peoples, the period of seeking and creating new identities, political and cultural emancipation, in the strivings to cast off foreign rule and in the dreams of independence and peoples’ own states, an important part of the Dubrovnik elite – intellectuals, scientists and artists – fervently and unexpectedly claimed their belonging to the Serbian cultural and national circle.

In his book Serbs in Croatia, Drago Roksandić writes about this very briefly, but with a fragment that speaks volumes, pointing out the “extraordinary phenomenon of Serbs-Catholics, mostly in Dubrovnik, in the period between the 1880s and the First World War. The movement encompassed a significant part of Dubrovnik nobility and intelligentsia.”

Roksandić also points out that this group is “of a very liberal inspiration and predominantly leads in the understanding between Serbs and Croats, although it also decisively defends its Serbian national choice in countless debates”.

Late historian Ivo Banac, himself a Dubrovnik native and member of a later, economic elite, dedicated an entire volume of his work published and printed in the US to this phenomenon. Although he tries, from his ideological position, to deconstruct this movement and relativize it as a temporary epiphenomenon brought about by historical forces and a specific moment in time and culture, paradoxically and unintentionally ironically, he gives the best and most precise definition of the movement. Since the Catholic Serbs, in a radical shift, considered religious affiliation secondary to national identity, and closely tied to the strong and numerous Pan-Slavism of a part of the Catholic elite not only of Dubrovnik, but of Croatia in general, Banac explains the very essence of the matter by writing that Catholic Serbs “disrupt the ‘rule’ of religious affiliation which existed up to that point”.

A fascinating and astonishing list of names appears when we examine which persons elected this apostasy at the time. Among Dubrovnik Catholic Serbs were such fundamental names of Croatian culture as Baltazar Bogišić, Matija Ban, Milan Rešetar, Lujo Vojnović. In this first line stood Medo Pucić as well, through his own choice, heart and convictions, perhaps most steadfastly of all.

“Descendant of Lazar’s peers”

Indeed, it suffices to read some of Pucić’s work to see this. Poetry speaks most directly and unreservedly about his fascinations and national, ideological and aesthetic passion, written in a sweeping romantic manner and the rhetoric of patriotic songs:

“The Serb steps hard

on fatal Kosovo field

(…)

O davori! Kosovo is

ours, ours, forever ours!

The living rays of light warm him

of nine birds of Jugovići…”

From Dubrovnik he writes that “every Serbian heart beats”. His incantation is “Glory, glory, glorious kindred”, and he rhymes “joys” and “holy bones” – “Relics of Serbian martyrs!” He even enumerates the geographical places, giving them the aura of the almost sacred and mythical:

“From Vučitrn, from Priština,

from Nerodilj, from Kačanik”.

He lists and repeats all the main points of the Kosovo and Vidovdan mythology, Lazar’s supper, the Kosovo Covenant and mythical heroes from the folk tradition in exemplary folk octosyllable.

“Look, ancient shadows rise,

those lordly bright faces!

Tsar Lazar, leader Miloš,

with Kosančić friend Toplica,

old Bogdan with seven birds,

love the earthly kingdom,

fortify it in Kosovo!

To the Serbian king, Kosovo-field,

Kosovo-field, give the throne!”

However, he does not create mere repetitions, such as existed by the dozens in the Serbian national and cultural circle of the time, both in Serbia and other regions where Serbs lived. Pucić goes further and creates a direct connection by connecting the Vidovdan myth with his world and the City itself:

“These words that fly from the heart,

from the once glorious Dubrovnik city,

wove into a garland in memory

the descendant of Lazar’s peers”.

The Catholic Pucić even varies the learned style of Orthodox prayer:

“Release your servant, God,

now I have seen the Savior,

I can exclaim under grey hairs”.

In the end, like old masters who embed a miniature self-portrait within a large composition, he invokes himself and his biography as “the teacher of Milan’s youth”.

Turning to hyperbole, expanding the metaphor and making an analogy with the independence of small countries pressed between larger empires, Pucić equates Serbia with Switzerland (!):

“Eager to compete with Helvetia

is the Principality of Serbia.”

Pucić celebrates the cult of Kosovo and Vidovdan praying to them from Italy and Dubrovnik, from his study in the midst of an urban environment, undoubtedly sincerely and devotedly. He writes an entire cycle on the First Serbian Uprising and its leader Karađorđe – the collection Karađurđevka from 1864.

Fanatical enthusiasm with little success

Even in the 19th century, for reasons not really concerned with art, Serbia was not indifferent to the fact that a man of such heritage as Pucić’s supported such ideas, as evidenced by the Serbian edition of Pucić’s collected works, published shortly before his death, in 1881, titled “Poems of Medo Pucić of Dubrovnik”. The affiliation with the City pointed out in the title was hardly coincidental, as it would have been had he been from any other area. Although two of his poems, “Sea” and “Life”, were included in Pavlović’s Anthology of Serbian Poetry in the 20th century, with our more balanced view from today’s standpoint we must say: Pucić is not a great poet. On the contrary, in most of his work he is a poetaster in the vein of romantic, Mickiewicz-like, belated patriotic rhymes, at a time when elsewhere in Europe a whole new age was beginning, Baudelaire had already written The Flowers of Evil and the advent of symbolism and impressionism was ushering in modernity and breaking with the past.

But what continues to fascinate about this exceptional figure lies elsewhere.

As is common with neophytes and those outside their motherland (in whatever sense), especially those who embrace a different identity, Pucić’s “Serbianness” is radical, stubborn and constantly in motion, and his writing is in a permanent hyperbole. His enthusiasm borders on fanaticism.

If exaggeration and superfluity of gesture is allowed in the literary art and is moreover part of a poetic style, especially of that period, Pucić’s scientific work, naturally requiring an attempt at objectivity and meticulousness, astounds with its fanatical zest and endless energy devoted to a special kind of recontextualization and reinterpretation of national history and culture. The most peculiar example of this is his extensive work in cultural history. In this work in which, as an older critical text states, “of all his historical work he gave the greatest contribution”, in two large volumes titled Serbian Monuments from 1395 to 1423, written in old grammar, script and orthography before Vuk’s reform, Pucić literally gives over the entire history and heritage of Dubrovnik to the realm of Serbian culture.

It is an impressive document, memorial and testament to a political, ideological, aesthetical and even metaphysical conviction.

The religious principle as the imperative of national determination

Medo Pucić died in 1882. The political and cultural power created by the movement of Catholic Serbs and its most prominent members held out for the next few decades, especially during the terribly dramatic years after 1914. In a historical irony par excellence, the movement dissolves in the first common state of South Slavs. In Croatian nationalist circles, where almost immediately after the creation of the new state began dissatisfaction and radicalization along ethnic lines – in the range from Radić to Josip Frank – the choice of Dubrovnik Catholic Serbs could only provoke hatred and hostility, especially since it was a movement which was, among other things, in essence the opposite of Croatian clericalism. But this is the lesser part of the negative influence on this small but elite group, the weaker part of the opposition to its existence.

There is an argument often heard in some intellectual and academic circles in Serbia in recent years. It states that one of the greater mistakes that the Orthodox hierarchy of the Serbs in the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes and the Kingdom of Yugoslavia has done is the resistance to the so-called “one-generational” Serbs and the lack of recognition of this essentially emancipatory, noble, possibly naïve and above all cultural project. The rule and principle of the Serbian Orthodox Church, already close to the government and almost a “state religion”, took precedence in ethno-national determination and became fixed in the formula: Serbian means Orthodox and, equally, Croatian means Catholic.

Had the principle championed by the members of the Serbian Catholic movement of Dubrovnik taken root, the ethnic map of our region would probably look very different today.

The preacher of Slavic reciprocity

After the formalization of the divisions and affiliations along religious and ethnic lines adopted by both the Serbian Orthodox Church and Croatian circles and in the process of the decline and disappearance of noble families of the City that had already begun, the members of Catholic Serbs of Dubrovnik disappear one by one, even biologically.

Not living to see the failure and end of his ideals, Medo Pucić died without heirs.

In the end, whoever we may be and whatever we may feel and think about this unique idea and cultural program, some of the fundamental beliefs Medo Pucić advocated still hold, regardless of national and ethnic affiliation. This is because, despite his fanatical enthusiasm regarding matters of nation, Pucić worked from a humane, humanistic, cultural, historical and perhaps primarily aesthetical position which became purely an ideal; he also worked from the position of unquestionable closeness and understanding between the two brotherly nations, something which has remained dangerous and subversive to all nationalist hegemonies to this day. He who, as one text states, “at the same time mentions Kosovo and Grobnik field”, writes, with whatever quality and poetic accomplishment, something irrefutable and vitally important then and in the future, throughout the terrible 20th century until the present day:

“Here two brothers met,

their faces both the same

(…)

same soul, same fair language,

and when it came to shaking hands – how strange! –

one is Croat and one is Serb,

one does not want to recognize the other.”

Warning us more than a century ago, he writes:

“Know each other, know each other, poor souls,

while the time is still right…

You are brothers, children of one mother,

nursed by the same milk.

What divides you today? Faith?

It is not from God if rifts it creates.

Law? Well you are both under foreign rule…”

Two hundred years after his birth and almost a hundred and forty years after his departure from this world, who could oppose these verses by Medo Pucić from Dubrovnik?

Translation from Croatian: Jelena Šimpraga

This post is also available in: Hrvatski