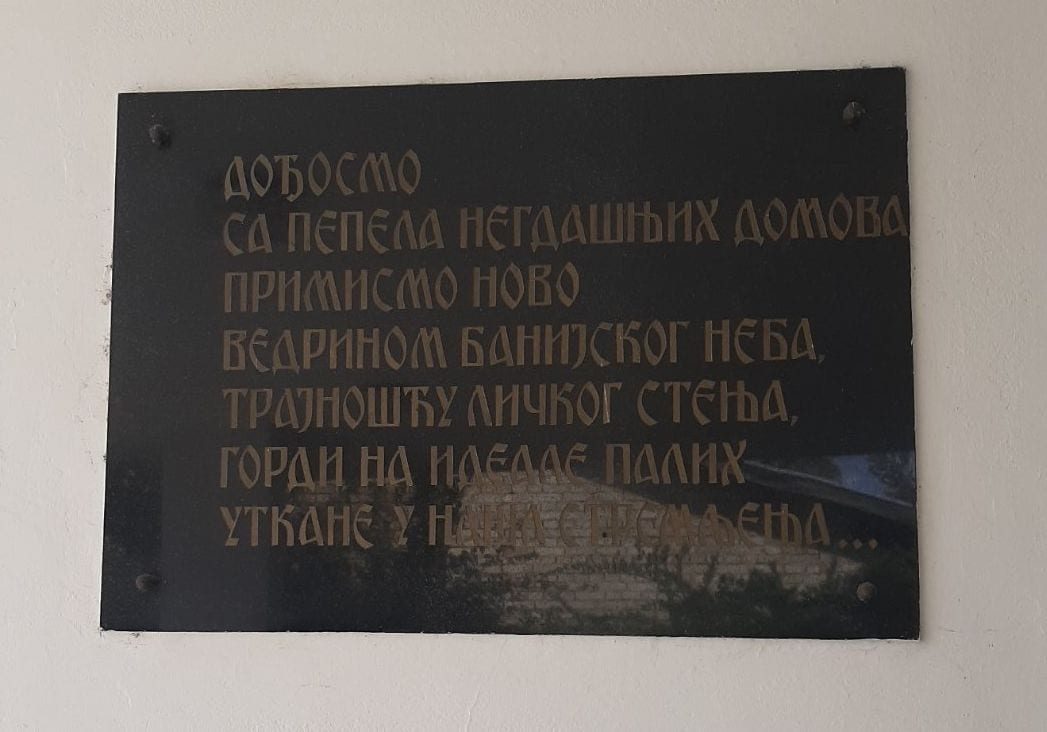

The songs of all ethnic communities which are constantly forced to move and live in uncertainty are, as a rule, filled with melancholy for a bygone life and lost mother country. This creates a culture of longing and remembrance that desperately try to save from oblivion “the life before”, which is in those memories always much better than the life after, even when it was difficult. The frontier people in Croatia, mostly Serbs, inhabiting areas of the former Military Frontier (Vojna Krajina), are used to this “suffering and hope”, as the title of a certain book says. A part of the identity of these people is the memory of both: home, family, daily hard work, joys and sorrows on the one hand and leaving that home and the traumatic journey into the unknown on the other. In the words of Serbian writer Milovan Danojlić: “We repeat the destiny of our ancestors and follow their paths with no choice in the matter, almost unconsciously – migrations are one of the cornerstones of our existence in this world.”

“People who arrived fleeing from evil”

One of these many Serbian migrations was the great migration from Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Montenegro to Vojvodina after the Second World War. The colonists brought with them not only their necessities, but also their beliefs and way of life, which constituted not only their micro-culture, but also their guiding principles and the meaning of their existence. They were recognizable by their characteristic speech, specific objects and local customs, which are ingrained in their identity in the new Vojvodina landscape to this day. Of course, they also brought with them their songs, somewhat rough from years of unstable life, always on the border and sad from losses of every kind, which seem to be inscribed in the fate of every Serbian community. To quote again Danojlić on the endless Serbian migrations: “These are people who arrived fleeing from evil, who are prepared for the worst and are still in a spasm of worry, and this spasm remains even after they settle and found a home.”

“Hateful enemies” – the best hosts

These first 436 families of colonists who arrived in the village of Čonoplja in Vojvodina, as well as those who came to neighbouring places in late autumn of 1945 and moved into abandoned German or Hungarian houses (often several families to one house), met a new, different world, circumstances and customs. As their descendants tell us today, these newcomers in need, wet from the rain, were welcomed and given shelter by a kind Hungarian man, which must have been exceedingly strange to them, as they had never met these foreign people in their old country. The principal of the school in the neighbouring village – its former pupils tell us – was German, which meant a different kind of discipline and approach to knowledge and learning. Moreover, the official terminology of the time named Germans as “hateful enemies”, but according to the descendants of the first colonists today, in reality these remaining Germans in Čonoplja and nearby villages were the main helpers to former frontiersmen in settling in and starting a new life.

“As children in our new homes in Vojvodina, every evening we used to listen about the hard battles with the Germans in Croatia and Bosnia in the Second World War, and the next day some other Germans from the villages we came to would teach our people about the work around the house and in the fields,” the elderly inhabitants of Čonoplja tell us today. As they tell us, there were no more Dalmatian or Kordun hearths about which the old and the young gathered, with polenta, sour cabbage and cicvara. Instead, they found ceramic stoves and wood stoves and completely different dishes and customs surrounding them. “Our women went to the local German and Hungarian women for instructions in cooking, knitting and pickling tomatoes for the winter. It would be very wrong to say the natives didn’t help us then,” inhabitants of Čonoplja say today.

A clash of different worlds

In the neighbouring village of Prigrevica, where Germans, Hungarians and Bunjevci also lived, the settlers were amazed to find some fifty or sixty pianos, rich libraries and completely strange furniture. “It was a cultural shock for our parents,” they say today. It was a clash between the settlers and the natives. The contacts among young people were also complex: German and Hungarian girls, dressed impeccably, would come to parties and dances accompanied by their mothers and aunts, while the newcomers would come in the company of each other. “But when that last German community was leaving Čonoplja in the early 1950s, the whole village cried and we all went to the station to see them off,” our hosts tell us. Regardless of the fact that there were still many fresh graves in those difficult times, alongside hatred and despair there were still in places warmth and love.

In any case, the colonists had to adapt, but they could not turn into Bačvani, into Lale, even if they wanted to. “We were all the same to them, although we know that there is a big difference between upper and lower Kordun, for example, and Bukovica, not to mention Lika, Dalmatia and Serbs from Žumberak,” Čonoplja people say. What is most important is the fact that the old country could not be torn from the heart, and it remains that way with many colonists today. They say that the natives of Vojvodina and the settlers are easily recognized even by the way they walk: people who arrived from hilly areas walk firmly, in large steps, and for them twelve kilometres on foot over a mountain is a common distance, while Lale walk casually and slowly, and the few kilometres to their farmstead are covered in a horse carriage. The settlers yell and talk sparsely, work quickly and sing sad and hard songs about the old country; the natives talk in a long and leisurely manner, work slowly since there is always time and sigh softly in songs about the old carriage, accompanied by the high notes of the violin. This is the complex and enduring puzzle of the multicultural life in Vojvodina.

In this clash of cultures and customs, the colonists in Vojvodina had to preserve something of their own or die out. Naturally, today the situation with the third generation of colonists is different due to assimilation and emigration, but very visible traces of the culture from the old country are still there and are painstakingly kept alive, regardless of the new times, today’s civilization of forgetting and the tomorrow which is always uncertain.

Partisan culture and culture for the people

Since the first wave of colonization from Croatia to Vojvodina included families who were victims in the Second World War and the fighters of the People’s Liberation Movement, they brought, along with traditional customs, a kind of “partisan culture”, which primarily manifested in the remembrance of the dead and in naming localities after people’s heroes from the fight against the occupiers. Therefore today in many colonist villages in western Vojvodina, in spite of today’s widespread trend of renaming streets and squares on all sides, we still find streets bearing the names of people’s tribunes, heroes and benefactors from Croatia: Marko Orešković, Rade Končar, Matija Gubec, Đoko Jovanić, Strossmayer, Miloš Kljajić, Nikola Tesla, seven secretaries of SKOJ…

This “revolutionary” culture had its own appropriate elements: communal evenings, people’s gatherings, poetry events in the agricultural cooperative and cultural centres where everyone was invited – peasants, workers and the honest intelligentsia, as the saying went. These plebeian temples also hosted everyone – from singer Esma Redžepova to actor Ljuba Tadić, and so, through this revolutionary overturn, the so-called “bourgeois art” was turned into – the culture for the people.

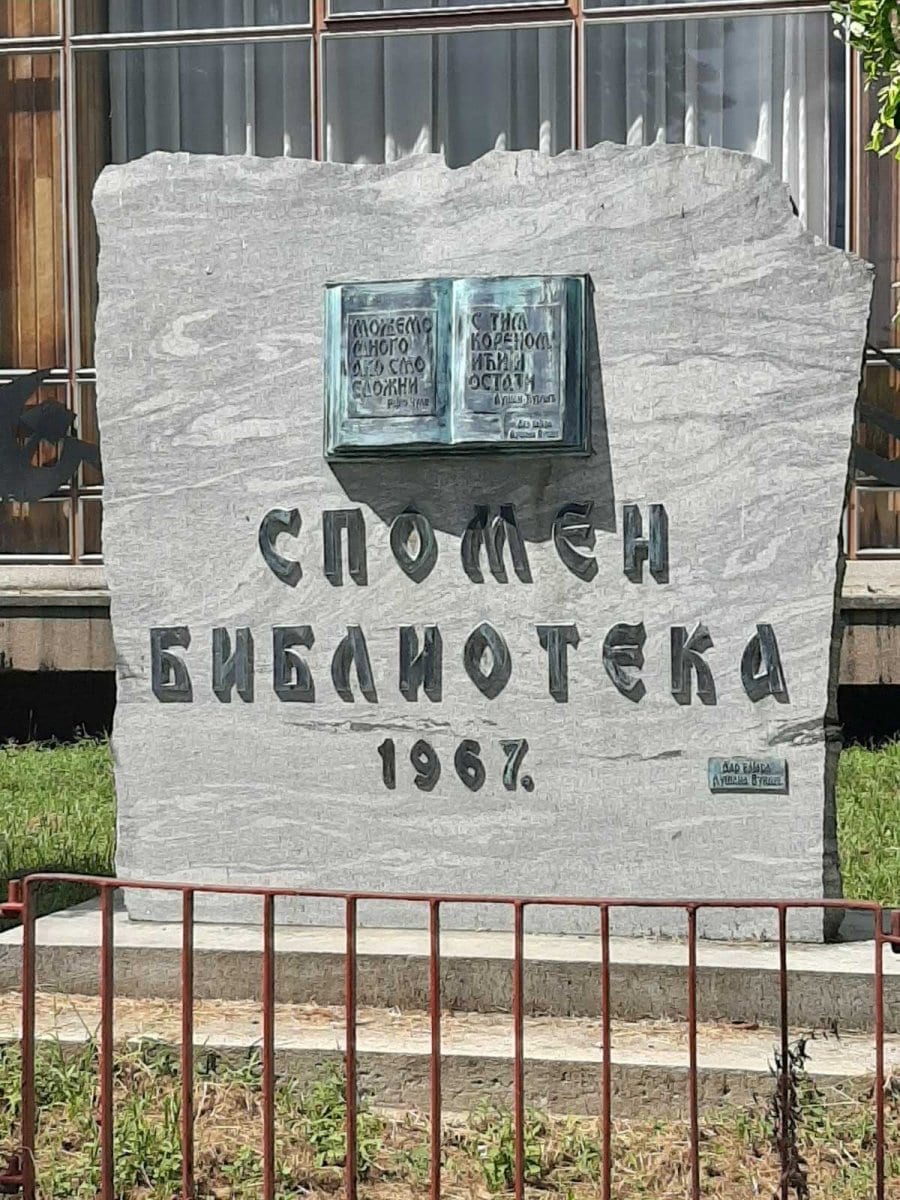

Through this merging of communist ideals and people’s enlightenment the village library in Prigrevica was also founded. In honour of the twenty years since the colonization, in 1966 this library was established as a memorial to those who gave their lives in the Second World War and as a new source of cultural development of the village. It was the first library in Serbia built using the funds of the local agricultural cooperative and the first library designated as a memorial for 967 victims of war from Lika and Banija, whose names are inscribed in the hall of the library and whose families settled in Prigrevica. The library was opened by writer Branko Ćopić, who left his verses at the main entrance: “New youth will come, it will bring new days, it will continue our unfinished songs forged in living flame.” In front of the library there is a bust of Rajko Čula (1912-1976), a war hero from Banija, once the undisputed leader of the village and the director of the agricultural cooperative that built the library, but also probably the only man in Yugoslavia who had been a prisoner of Goli otok and had a monument erected in his honour.

The flame of old customs lives on

However, the colonists also sang their old songs and cherished traditional customs, always looking back to the places where they came from. So it was that in these times, when the new socialist man was being created, the flame of the old folk tradition was quietly kept alive, and it was a tradition that had nothing to do with politics or ideology, but was connected to the way of life in their old homeland, which was the only one the colonists really knew. Our hosts in these colonist villages say that there are in Vojvodina some fifty folklore societies founded by former inhabitants of Lika, Dalmatia, Banija and Kordun. Today most of these first colonists are gone, the times are different and there is far less money for culture, but the descendants of these settlers still jealously keep alive the flame of the old customs. For example, in the villages Stanišić and Riđica, where colonists from Dalmatia settled in 1945, the tradition of the old country is preserved by the “Izvor” folklore society and the Women’s Society, which have established ethno houses where one can see furniture and many other objects brought from Bukovica and the areas around Benkovac and Obrovac. “I dream of the old country every night, although I lived there for barely 14 years and here for 68,” says one elderly inhabitant of Stanišić who hails from Plavno near Knin. “Here I saw mud for the first time; there was no mud in our rocky karst.”

Folklore society “Vuk Stefanović Karadžić” in Čonoplja not only takes care of the traditional songs and dances from Kordun, where Čonoplja’s settlers are from, but it also cares for the ethno-library and museum, which houses traditional objects, tools and folk costumes of the people who mainly lived in the areas around Slunj. Their president, Milka Bosnić, tells us that the concept of this ethno corner is based on the hearth as the basic and key element of the traditional family life in Kordun.

“We tried to reconstruct the old way of life by the hearth: people lived, cooked, ate and gathered there. Around the hearth our old folks all ate not only from one bowl, but also with one spoon,” the president of the society explains this modest and frugal way of life. She says that in arranging this traditional collection it was important to show the characteristic objects and their names and to connect them with a specific way of life. “No one knows what “vučje” are anymore – they are vessels in which we brought precious water from Korana, which was kilometres away. Or, nobody knows what it means to wash the clothes at the river, what the words “rubina” or “prakljača” mean, or what “sofra” is, and that is a low table for eating while seated on the floor. We don’t want these things to be forgotten,” Mrs Bosnić says for P-portal. That is why the society takes special care of the original details in traditional songs and dances and consults ethno-musicologists in Vojvodina on these matters.

Harmony between all 26 communities in Vojvodina

Colonists’ folklore societies gather at festivals where they share experience and advice on customs and tradition. One of these is the festival “To Our Kin and Progeny”, organized every year by the Serbian Cultural Centre from Bačka Topola. Serbian and many other folklore societies perform at these ethno festivals – there are 26 different ethnic communities registered in Vojvodina and the cooperation and synergy between these societies are on an enviable level. However painful and even tragic these various migrations to Vojvodina were, this region a hundred years ago or today is not physically or culturally possible without its many ethnic communities.

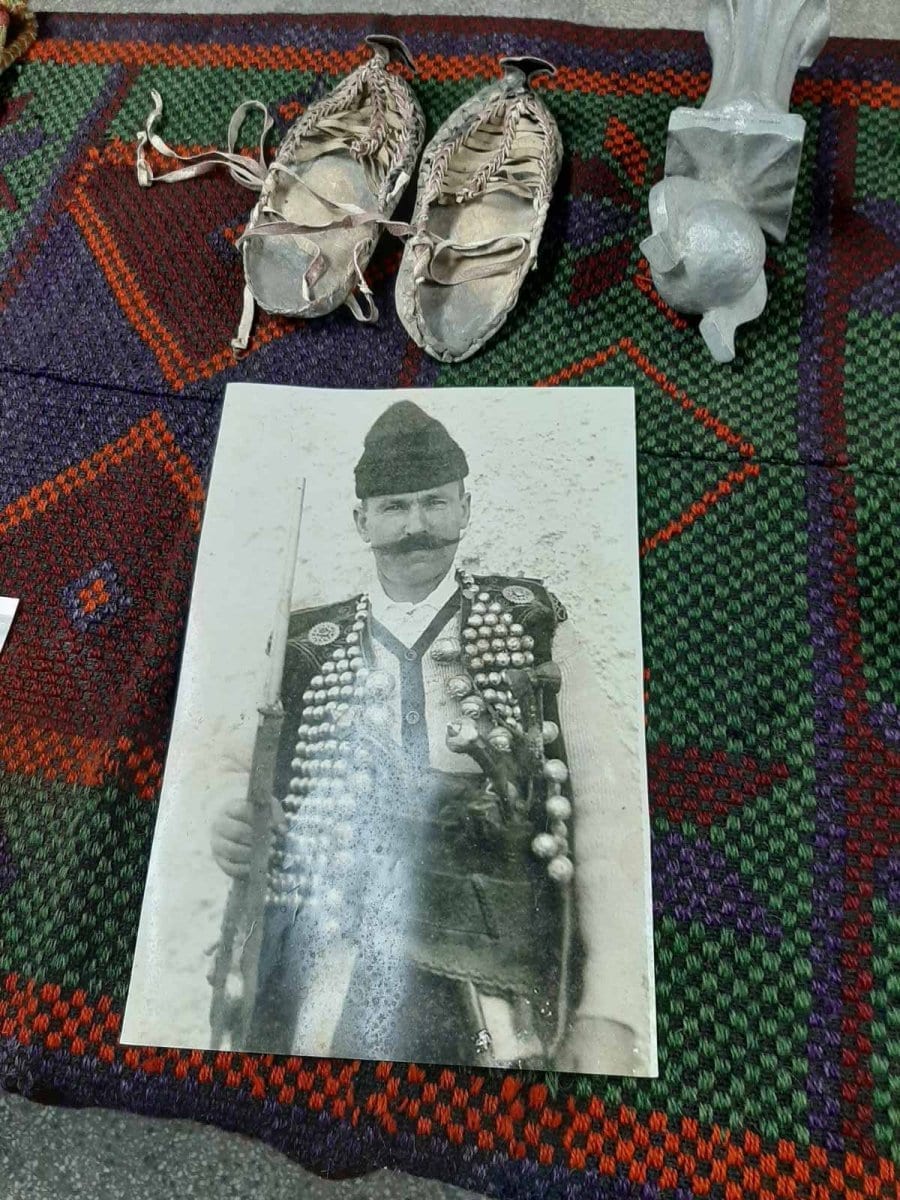

In the village Prigrevica in 1968, library clerk Momčilo Todorović gathered old objects from colonists from Lika and Banija and displayed them in front of the cultural centre. This was a call to the inhabitants to search their storerooms and attics and bring what they still had of those objects they had brought with them over twenty years ago. This was the beginning of the well-organized Prigrevica Ethno Museum, which students on excursions from other colonist villages and towns in Vojvodina still visit. “Every object has its story and tells us something about the fate of the people and their life in Lika and Banija,” current curator Momčilo Todorović tells us.

The objects are very varied, from ornaments for women’s clothing and waterproof jerkins of shepherds from Krajina to small cannons whose shots warned of the approach of the enemy. “It is a miracle that we managed to collect all these items from the people settled in Prigrevica because their houses were burned and plundered so many times during the Second World War. It is incredible that they managed to bring anything with them here,” Todorović explains. There are weapons dating from the times of the Turks, women’s purses, bells for cattle, knives for pruning grapevines, distaffs, wooden cartwheels and something in several shapes called “nadžak”, which is a metal tool with a small axe on one side and a hammer on the other. “You’ve heard, I hope, of the expression ‘nadžak-baba’ that exists in the people?” curator Todorović asks us.

Only memories still remain

Folklore society “Vuk Stefanović Karadžić” from Čonoplja will celebrate its very respectable 75th anniversary in a few years, and the whole village will be on the streets to connect with their ancestors, customs and long-abandoned hearths through memories somewhere in the cosmic heights. A kind of theatre play will then be performed, which will hopefully bring the image of Kordun of long ago into the imagination of its colonist descendants. Do the colonists ever return to the old country? “Actually no, because there is no one there anymore,” says Mrs Bosnić. The last meeting, she says, between the colonists and their kin was more than dramatic. “It was after Operation Storm when all those people came here. We were all at the Community Centre, we all cried as though we lived through the ‘Storm’ again,” Mrs Bosnić says. After this tragic exodus, the folklore societies of Vojvodina intensified their activities, searching even more fervently for their identity: old papers were rifled through to find the permissions for colonization, the names and photographs of fathers and grandfathers long gone were searched for, old objects and memories were brought out of the dust… “We colonists from 1945 knew what the drama of adjustment meant, and we knew that awaited our cousins who came in 1995. We helped the refugees from Croatia as much as we could and they more or less managed to secure their existence, but both we and they have to work to protect our memories, the only thing we have left.” Because, Mrs Bosnić says, “it is difficult to live with the feeling that you don’t belong anywhere…”

Translation from Croatian: Jelena Šimpraga

This post is also available in: Hrvatski