A damp, cold and gloomy February morning in the largest “city of the dead” in the Republic of Croatia. Footsteps both sharp and dull ring out in the dead silence; not a soul is in sight. A curtain of boring and monotonous rain comes down on Zagreb’s Mirogoj Cemetery, obscuring the view. Only the raindrops are alive, connecting and merging, turning into small streams and then into veritable small torrents. They run down headstones; thousands upon thousands of them murmur and gurgle through the passes and flow away towards the vale and nearby forest. In this river, by now no longer small, tears drown – both rain tears and real ones. Thoughts are alive, too, while the glance flits from one tombstone to the other, each hiding one or several life stories and destinies, many dead and long-gone loves. Who are these people; does someone remember them today, or have they vanished forever in the oblivion of time?

Remembrance and admonishment against the darkest period

First names, family names and dates follow one another. There are humble and there are monumental last abodes, but in death everyone is equal. Some are long gone, and their monuments are sad and worn by time, while others’ are still well-tended. Families Hećimović, Juričić and Bahtijarević, the Jožinec family, then families Papići and Benci… and we come to the Plot 142, bordered with a hedge on three sides. Candles and flowers, scattered toys and a small, discreet monument, as well as a small tombstone in which it is carved: “Several hundred children from Kozara are buried here.” Only a few square meters hold the last resting place of several hundred innocent girls and boys. Nearly a thousand innocent little lives. The story dates from not so long ago, from a period darker than the dark Middle Ages.

In the year 1942 the world was already deep in the Second World War, the war that claimed the largest number of civilian casualties, the war which was fought not only for territory and resources, but in which people were tortured and killed because of their religion, nationality, race, political orientation… To unfathomable proportions. Unfathomable, because those who started and waged the war did not spare anyone, not even the most vulnerable ones – children.

In the struggle for their lives

In June 1942 German and quisling units started Operation Western Bosnia in the area of the Kozara mountain and Potkozarje, inhabited mostly by Serbs. Despite the unyielding resistance of the partisans and the unity of local Serbs, Croats and Muslims, fascist forces surrounded the entire area and started the systematic extermination of the local civilian population. Thousands of people were killed on the spot, while thousands were sent to concentration camps. Thousands of Kozara children were not spared either.

The power they were ensured by their powerful German ally caused the Ustashe to lose all reason and erased their last shreds of humanity. Because of them, Kozara children were no longer awakened by sunrays shining through the thick Kozara forest or by their parents’ voices, but by gunshots, detonations and the sounds of war.

Camps more terrible than death

In his book Jasenovac – Tragedy, Mythomania, Truth, historian Slavko Goldstein writes that the people from ravaged Kozara were placed in Jasenovac area concentration camps of Stara Gradiška, Uštica, Mlaka and Jablanac. Due to overcrowding, new temporary camps were established in Prijedor, Kostajnica, Cerovljani and Novska. The “most able and healthy ones” were sent to concentration camps and work camps of the Third Reich as slave workforce. Thousands of Kozara people were sent to villages in Slavonia, Posavina and Moslavina, where workforce was needed due to the conscription of men into the army. According to data by Dragoje Lukić, the author of the book The War and the Children of Kozara, 68,600 people were expelled from Kozara, among them almost 24,000 children under the age of fifteen.

Through the effort of Diana Budisavljević, 6230 out of more than 12,000 children in Stara Gradiška camp were rescued. These and many other children were hungry, thirsty, barefoot, sick, exhausted and separated from their parents, helpless as they themselves were.

They survived Kozara, but not the consequences of the camps

In her book Diana Budisavljević – the Unsung Heroine of the Second World War, according to the List of Children Victims, historian Nataša Mataušić states that during 1942 children were rescued from Ustasha camps Stara Gradiška and Jasenovac and camps in Mlaka, Jablanica and Koštarica. The number of rescued children in the Zagreb area is between 6679 and 6733, and the final number of deceased children is between 881 and 904. Data differs between sources. She explains that the death rate among the children depended on the medical condition of individual groups of children that arrived in the transport, as well as on the conscientiousness and care of the doctors, nurses and women who took care of them and the people who oversaw their transport.

The institutions in Zagreb where the children were placed were the Institute for the Education of Deaf and Mute Children, the State Children’s Home at Josipovac, the City Hospital for Infectious Diseases under the management of NDH, the Hospital for Infectious Diseases, the Rebro Foundation Hospital, the Children’s Clinic at Šalata… The children who died in transport from the camps or in Zagreb hospitals, shelters and families that took them in were buried at the Mirogoj Cemetery in Zagreb, at Plot 142.

The grave that was not talked of after the war

Mataušić quotes the conversation between Duško Tomić (author of the book On the Paths of the Death of Kozara Children) and Josip Pavičić, the Mirogoj graveyard keeper at the time, in which it is stated that the Red Cross, city authorities and other church organizations took care of Plot 142, and that the bodies of children arrived daily in small caskets or wrapped in cloths or sheets. Since it was known those were mostly children from Kozara and Potkozarje, Plot 142 was simply called “Kozara.” Pavičić explains that this tomb was not talked about after the war, but that later an appropriate monument was erected. Duško Tomić states that 862 children were buried at Mirogoj, while the List of Victims Deprived of Life (which the Orthodox parish authorities in Zagreb gave to the State Commission for Determining the Crimes of the Occupiers and Their Accomplices in 1947) lists 802 children.

Dehumanized name of the terrible tomb

The name of the tomb of the Kozara children, Plot 142, sounds like a plot of land which, if the real estate agents are successful, will be sold and where one day a family home or offices will be built. Only when one comes to the Mirogoj Cemetery can it be seen, because of the children’s toys, flowers and the monument, that this is a children’s tomb.

Historian Nataša Mataušić reminds us that experts have worked on this topic, publishing numerous books, studies, papers from scientific conferences, monographies and memoirs.

“Dana Budisavljević made the drama-documentary movie; my book was published; scientific conferences, such as the one about the children’s camp in Sisak, are held; in Sisak every year at the children cemetery victims of crimes against Serbian children are commemorated,” Mataušić comments the current state regarding this issue.

However, Kozara children buried at Mirogoj are not commemorated or reminded of.

“Why? I do not know the answer to that question. Indolence, forgetfulness… But if you have been there, you could see that the children from Kozara are not forgotten… At least not by those who survived this tragedy,” says Mataušić.

Candles for the Ustasha

Instead of commemorating the child victims of the fascist NDH, in 2019 at the Mirogoj Cemetery, commemorating the European Day of Remembrance for Victims of All Totalitarian and Authoritarian Regimes, Croatian Prime Minister Andrej Plenković, Minister of the Interior Davor Božinović, Minister of Croatian Veterans’ Affairs Tomo Medved and special advisor for social affairs, academic Zvonko Kusić lit candles in front of the monument to the defeated Ustasha army. They turned their backs on the Kozara children and went towards the exit across from which lie many antifascists who fought for Croatia. They turned their backs on the antifascist heroes of our region – Rade Končar, Josip Kraš, Vladimir Nazor, Ivan Ribar – who also lie buried at the Mirogoj Cemetery. They turned their backs on those whose fight was for the unity and freedom of all our nations, and not for divisions, hatred and the struggle for survival we face today. Instead of championing the globally recognized antifascist values, in reality representatives of Croatian authorities court fascism in their irrational flight from the “specter of communism.” The Ustasha salute “Za dom spremni” is not prosecuted, Ustasha symbols in the public space and public events are tolerated, not all victims of the criminal Ustasha regime are honored…

Subjective interpretations of facts

In NDH, Ustasha cleared the territory of all undesirable “elements” according to race laws copied from Nazi Germany, their allies. The undesirables were Serbs, Jews, Roma, progressive and humane Croats who did not approve the Ustasha regime, primarily communists… To this day there are disputes concerning the circumstances of the crimes and the number of victims, as in the case of the Jasenovac concentration camp. All the false claims are disproven with clear arguments by notable historian Slavko Goldstein.

Revisions and distortions of history in the countries of former Yugoslavia are becoming increasingly more frequent and senseless. “Today everyone interprets the facts the way it suits them in order to prove conclusions already made. Unfortunately, the history of the Second World War is still full of disputes and controversies, and it always seems we have yet to ascertain the truth about certain events and persons who marked this period of our history,” Mataušić explains.

For the truth and the dignity of the victims

When asked how it was to explore such a difficult subject, a tragedy of unfathomable proportions such as the suffering of children in NDH, Nataša Mataušić says: “It was incredibly difficult… I cried; I did not sleep for nights. I stopped with the research and then resumed it; I argued with my family because they could not understand why I did not give up even though work on this subject exhausted me terribly… I am glad I did not although there were moments when I could not continue… The photographs of the children’s camps in Sisak and in Gornja Rijeka… The photographs of children who died and children who, despite the help given, were condemned to die… The emotional testimonies of the surviving children… All of this and the desire to establish the objective truth, to give back dignity to those who were robbed of it, to show gratitude to all those who helped save the children – Diana Budisavljević among them – kept me going,” the notable historian concludes.

Bright examples of humanity

Thanks to the action of Diana Budisavljević and her associates, according to the data from her files, around 12,000 children were rescued. Much more important than the exact number is the fact that in those inhumane and wicked times many people found the courage and risked their lives to save the lives of those who were helpless. Luckily, such people existed in other countries, too; there were many who fiercely fought for every life with determination, humanity and courage. Such were the lesser-known Polish social worker Irena Sendlar, the well-known German industrialist Oskar Schindler and many others. Nevertheless, when we talk about them, we must not forget or diminish the role of all those other, now “nameless” people who supported them and without whose help they would not have succeeded. Owing to such people, we can still believe in humanity, despite the wars which are waged even today.

The short and terrible path from one forest to the other

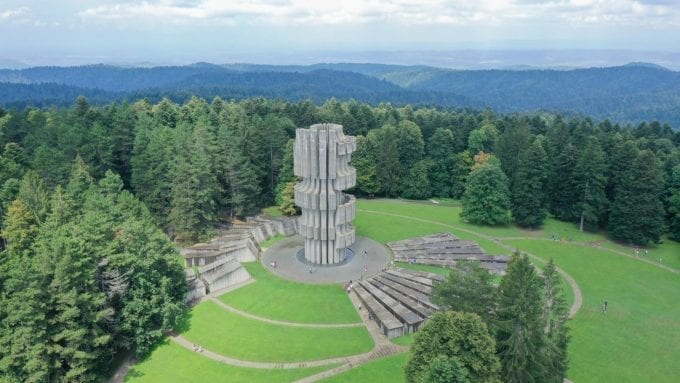

Kozara is still green and beautiful, like in that woeful 1942, but it is forever changed and impoverished because its people forcibly left it for concentration camps and death. Dušan Džamonja’s magnificent memorial complex on Mrakovica shines light on the memory of the tens of thousands of victims from Kozara, giving them back their sacredness and light, the same light that awakened and warmed them before they were led to a violent and early death. The forest stretching behind Plot 142 reminds one of the Kozara forest, where long ago the older children buried here used to play, laugh and dream of a life that was just beginning. The life cruelly cut short by fascists – people who we cannot and must not call people…

A rainy and sad February morning, footsteps both sharp and dull ringing through the dead silence of Mirogoj, not a sound or soul in sight. Or is there? Listen and look a little closer, and you will hear the gleeful shouts of happy children at play. The rain has stopped, and the sun is shining through the clouds. The children of Kozara run into the arms of their equally happy mothers. We watch them, ourselves happy, wresting them from oblivion. Every one of them has their name again.

Translation from Croatian: Jelena Šimpraga