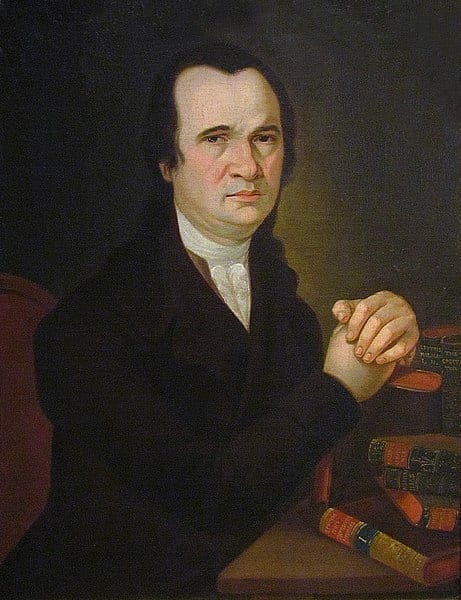

Next year will mark 210 years since the death of Dositej Obradović, the greatest modern Serbian enlightener and, alongside Vuk Karadžić, the greatest reformer of culture since Saint Sava. Moreover, two years ago it was 210 years since the founding of Velika škola (Great School), the first institution for higher education in Serbia, which then, under Karađorđe, was only beginning to free itself from the centuries-old reign of the conqueror who had set it back hundreds of years. Radio-television of Serbia is currently showing the documentary series “Dositej – voyager of enlightenment” by Valentina Delić and colleagues, an ambitious series about the life of Obradović. All this gives us good cause to talk again about this extraordinary man and one of the key figures of national culture and history.

Dositej Obradović is little-known and of small significance to Serbs outside Serbia, especially those in Croatia, in spite of his many travels and stays there and the mark that he left

Interestingly, this TV series is only the first larger documentary project about Dositej (not counting the old TV series produced by RTB), which is a sign not only of the problematic status of culture, but also of the enduring, if not always visible, misunderstanding about the significance of this remarkable man, who practically single-handedly introduced and spread ideas of the Enlightenment in regions populated by Serbs and who told of the ideas, history and facts about his people wherever he travelled. And he travelled a lot, perhaps more than any other notable Serb until the twentieth century, in a time when travelling was rare and the culture mostly sedentary, with complicated obstacles for travellers crossing from country to country and empire to empire in Europe of those times.

It is also interesting, sadly in a negative way, how little-known and little important Dositej is to Serbs outside Serbia, especially those in Croatia, in spite of how much he travelled and stayed there, not to mention the mark that he left there, in Dalmatia, Slavonia and Croatia.

Equal to everyone he meets

There is another important reason why Dositej should be better-known to people here and why the knowledge about him – the man who dedicated his life to spreading knowledge among his people – should be taught to new generations.

He is the first who showed the way to future generations of national intellectuals, who will find themselves scattered widely in the periods to come. There were many of them in almost every generation until today. Dositej was the first to walk confidently through the western civilization, without a complex about his origins. Linguistic and cultural revolutionary Vuk Karadžić was undoubtedly a genius, but we from later generations, especially from western regions, did not look like Vuk with his wooden leg and Turkish fez and did not want to be seen as something exotic and different. We have tried to escape from this for generations, and this is the point of separation of Serbs outside Serbia from those within, who suffered under foreign, oriental domination. This point is crucial for our affinity with Dositej: he walked the west, here where our ancestors after the Great Migration guarded that very border of civilizations, as an equal to all that he met and all the time learning from everyone he could. It is difficult even to imagine what kind of resolve it took for him, a lone man from the edge of Europe, a wanderer from provincial Hopovo in Vojvodina and from Banat near the border of Asia, to behave confidently and autonomously, speaking for himself and his national culture and heritage that were still completely unknown to the world. He was their ambassador everywhere he went, just like he spread goodness everywhere: friendship, love, the spirit of reconciliation, dialogue, peacemaking, knowledge and enlightenment, freeing those words of the clerical echo and making them universal, secular and for all people. Simply put, Dositej was the pride of his people in the world.

What is more, he left an autobiography unlike any other in this culture, written in a wondrous language at the border of language epochs, in a style mixed, but most of all his own, recognizable from the first line on every page. Fully titled The Life and Adventures of Dimitrije Obradovič, Named Dositej as a Monk – Written and Published by Him, it is a book permeated by a sense goodness, exceptional clarity, enormous erudition and literary, but also emotional, intelligence and brightness. In the context of the national culture, he skipped centuries in every regard.

That brings him closer to the part of his people who lived and still live in Croatia.

It is worth reminding ourselves how these travels were described, especially the parts where the future giant of Serbian, South Slavic and European culture crosses into these parts for the first time with a friend from Hopovo.

Journey through Slavonia

The first new geography he travels to is almost the same as the one he left – he enters Slavonia. The meeting with the people there is almost like from a novel and begins with familiarity, goodness and hospitality between people:

“We took the Osijek route, crossed into Slavonia and, while on our way to Pakrac, something unexpected happened in a village. We heard songs and the talk of many people in a yard. ‘Do you know what it is?’ asked Atanasije. ‘I am thirsty anyway; let us enter and ask for water and see what goes on here.’ We entered. And there – a wedding and celebrations. When we asked for water the bridegroom’s mother told us: ‘Dear travellers, today we don’t drink water here, but wine, and if you want, come in.’”

The speech of the woman, with its length and intonation, is still characteristic of Slavonia and Vojvodina today.

Dositej continues:

“We entered. And when we told the wedding guests that we came from quite afar, the best man exclaimed: ‘Ha, it is lucky when guests from afar come to such a celebration!’ He told us to sit, eat, drink and be merry. They asked us about the wheat harvest, the vineyards and other matters in Srem (…)”

Dositej notes the use of “ikavian” forms characteristic of Šokci in the host’s speech, signifying that it is a Catholic, Croatian family. The hosts find out that the travellers came from Srem and, in line with what we said earlier about the rarity of travel and the notion of distances in those times, call that “from quite afar”.

Dositej writes about the hospitality of these people: “We stayed the night there and the next day were treated as if we were their kin; with kisses and embraces we parted from them. We found such warm reception not only at weddings or in this one place, but everywhere as we crossed Slavonia and Croatia.”

Man from a distant future

He makes an important point in the next sentence, one that is often believed today as well: “Everywhere good people rejoice to meet those from afar who speak the same language as they.”

He then adds a point that will be the source of greatest trouble for us for the next two centuries: “Love for other people is natural for them and nothing divides and estranges them more than the churches, both Greek and Latin!”

Decades later, remembering this first meeting with these people who are most like his own, his experience of monastic life still fresh in him, Dositej said: “The Church’s duty is to accept people and unite them in love and kindness!” He finishes truthfully, but with seriousness and a warning: “Would it not then be of the greatest benefit for good people to see this clearly? To be told that they can belong to any Church and still be joined in friendship, respect and love?”

“I am not a schismatic”

Publishing these lines in Leipzig, Germany in 1783, this is a man who clearly comes from a distant future, a future with its good, bad and worst periods when his teaching will be alternately accepted and abandoned. For Dositej is neither a blind idealist nor naive. Writing about this same wedding, where he was accepted warmly and as a brother, he adds something a little darker, a little more admonishing:

“And so we talked pleasantly and openly, listening to music and watching the merry youth dance. Then a large student appears and sits across from me, listens to our talk for a while and turns to me, saying: ‘By your way of talk I would say you are a schismatic.’”

This is a sentence with that familiar tone, where the word “schismatic” will be replaced with other nouns that signify religious and, most frequently, national-ethnic identity, or with pejoratives like this one, but a hundred times worse.

However, Dositej, although kind and conciliatory, answers resolutely: “’I am not a schismatic,’ I answered him openly, “but an Orthodox Christian.’” Dositej knows who he is and does not hesitate to add: “and better than him, if he wants to know”.

Of course, a dispute about the authority and the “primacy of the Pope and of the Greek and Latin churches” begins. Dositej, well-read in the sphere of Orthodox thought, is ready for the discussion and could “argue about this so that the ground beneath me trembles”. His opponent starts using Latin (which Dositej still does not know), but Dositej tells us that the other guests and the hosts, “all sons of the Roman church”, praise Dositej because, in a brilliant rhetorical moment, “whatever I say, they understand”. In other words, they understand the South Slavic language, unlike Latin. The combative student threatens with jail, but, according to Dositej, the hosts again defend their guest and show the attacker the door. We will never know whether this is an idealized version, but honourable Dositej’s account is worth the trust. Either way, it did not help in the distant future.

.

“My book will be for anyone who understands our language and who, with a pure and true heart, wants to enlighten their mind and improve their character. I will not care in the least who follows which faith and law, for that is not important in today’s enlightened age. Following faith and law, all men could be good. All religions are based on the law of nature; no religion in the world says: do evil and be unjust.”

Letter to Haralampije, 1783.

Stay in Zagreb

After Slavonia, Dositej spent some time in Zagreb, learning Latin in the Jesuit gymnasium, the same one that exists today. It is unusual to think that Dimitrije Obradovič, named Dositej, was for a time our fellow citizen, but that is just another part of the insufficiently explored and recognized local history. We can only hope that one day our culture will turn to this part of its heritage, for it is its heritage, whether one likes it or not.

Dositej’s path was again changed by a man from our area. Although he intended to go to Russia, like many young Serbs of that age (a tendency that will already change in the next generation) and in that stage of development and education, which was formed according to the eastern canon, one meeting was crucial for him. Asking him where he intended to go, Danilo Jakšić, eparch of the Karlovac area from Plaški, advised him to cross into Dalmatia, where he could earn enough for his trip to the east (which would later not happen, luckily for us) by teaching pupils. Dositej headed towards the Adriatic and came to the Dalmatian hinterland, where he would stay the longest. This region is the birthplace of Dositej as a teacher and enlightener.

Dalmatian Hinterland – one of the birthplaces of the modern written language

He arrives in Plavno on the recommendation of Krupa Monastery, goes to the “furthest serdaria” of the Knin borderland, at the very border between Turkey and Venice, to a stony, poor and harsh region.

Here, in this wasteland – which is another point of immense importance for national culture – where life is desperate and dangerous, Dositej starts to write – and he writes in the language of the people.

This language is still far from the ingeniously simplified, refined “Tuscan” of

Vuk Karadžić, which we call ours today in all our national variants. Regardless of that, one of the birthplaces of the modern national written language is a small village in the Knin borderland, where a man from Banat, a runaway from a monastery, first started to write about serious things. The perfecting of his writing as his texts grew into books and were then published would have revolutionary consequences for the culture, language, education and nation as a whole.

Dositej was “his own army”, an individual, a traveller, but also a decent man when he slept in the houses of friends or in any other place, always sociable, conversing and gathering experiences. Dositej experienced many difficulties in his travels; apart from loneliness, one of the hardest was “dire poverty, destitution” – the lack of financial security.

Only a man of enormous wisdom, strength of will and true light in his soul could afterwards describe his trials during those formative years and travels without sinking into moralizing, humourless self-pity and dejection as the result of his destiny, his periodical poverty and the difficulties of travel. Even when he writes about all this, there is a feeling that better times will come, that they already have come, because Dositej writes about this in the future, in The Life and Adventures. This remarkable man must have felt a lot of fear and even more loneliness. It is not only because he travels alone and as a member of a small and barely known people that have yet to be formed as a nation. As an enlightener and an intellectual with a vision he must have known that he was doomed to be alone, that few of those he met on his adventures would be able to understand or follow him in that sense. Who knows what kind of challenges he faced to preserve his undoubted decency and honesty when finding decent lodging for the night and a supper? Regardless of that, there is never lamentation over it. If he kept silent about something, it was not out of cowardice and dishonesty, but out of his belief in his just and noble mission and the need to give “his children” encouragement for the future.

“So that the life of Serbs in Dalmatia is not forgotten”

Dositej taught in the village school in Plavno near Knin more than two hundred years ago, before he went to Belgrade. He befriended Simeon Kuraica in Plavno.

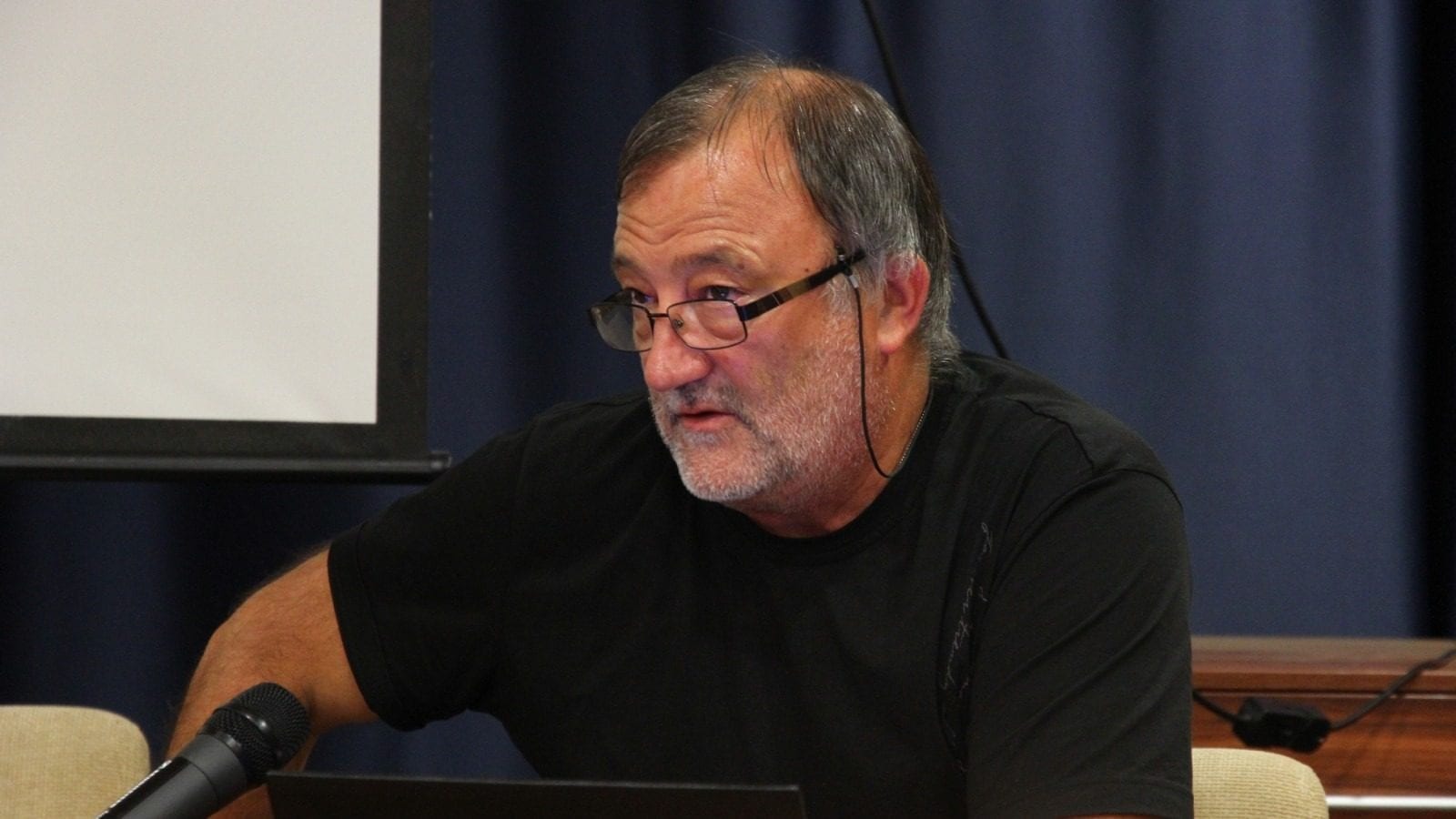

A while ago there was news in the media with the exciting, fascinating information that this Kuraica, from the region that went through several disasters in the next two centuries, still has direct descendants. One is Milorad Kuraica, who studies the life of Dositej today and even succeeded in setting up an exhibition titled “Dositej and Serbian Plavno”. The news also stated that the full project is supposed to provide for the restoration of the house where Dositej lived in 1769.

But then we have the second part of this news: Milorad Kuraica has left Plavno and now pursues his valuable and honourable project from Serbia. Undoubtedly everyone who read this thought the same, which is confirmed by the last, saddest sentence from the news about the noble project:

“The restoration is supported by the association of Dalmatians from Subotica.”

Or maybe the last piece of news is the saddest:

“The basic mission of the members of the association is that the lives of Serbs in Dalmatia be not forgotten.”

Dositej Obradović carried the heavy burden of a mission and a destiny, but he was not a tragic figure. The joy and the light of his task and mission, which from dreams became physical and spiritual reality before his eyes, give sense to this loneliness, and such great efforts are realized into great deeds and a future.

Some of this must have left traces in his people. We have to believe that the future, the horrors of the past notwithstanding, will bring to these people – however many there be left – and to their best and most persistent individuals some reward for their efforts in the name of future generations. And, as Dositej’s people, in the name of the ancestors.

Translation from Croatian: Jelena Šimpraga