Film editor and director Danilo Lola Ilić was born in Vranje, grew up in Fažana, was a gymnasium student in Pula, an academy student in Belgrade and an even greater student in Ohio. Because of all of this, and especially all the people he has met and documented on this path, he considers himself a citizen of the world. He says that he sees the category of nationality solely as the beauty of a society and in no way as a cause for creating divisions and inequalities. With a rich movie career behind him, he refuses to be a cog in the movie industry and has for decades done his projects independently and most often alone, which allows him to form special relationships with his interviewees and the subjects he works with.

Hist last movie, Erik, is included in the programs of film festivals around the world, on almost all continents, and will soon be part of the Martovski Festival in Belgrade. It resists the stereotypical portrayals of persons with disabilities in the media, which are either full of exaggerated pathos or show them as superheroes. In the interview for P-portal, Danilo emphasizes what was most important to him in telling Erik’s story.

“My friend Erik is a kind of superhero for me; he is a person I greatly value and respect. I am very glad that the movie Erik is traveling the world and that the festivals and audiences are receiving this story very positively. Erik is not a person defined solely by his disability – as he says himself, it is only a condition. He is a person who is much more than that. Despite difficulties, he composes, sings, performs; he is one of those rare people who delight with their charm and positive energy. A stereotypical portrayal would be an insult to Erik. The movie, of course, includes biographical parts as well as parts important to other persons with disabilities, but Erik is above all a movie which should motivate us to take care of each other and be our best selves in everything we do,” Danilo says and adds that there is a lot we can learn from Erik.

Erik is above all a movie which should motivate us to take care of each other and be our best selves in everything we do

You mentioned that you still do not know if the movie will be a part of the competition program of the Martovski Festival since “the only Serbian thing in the movie is you.” Outside of this example, how important are the categories Serbian – Croatian to you?

The Martovski Festival in Belgrade shows Serbian productions and co-productions, and since Erik is neither, it will probably be a part of the festival’s Panorama program. Nevertheless, the Martovski Festival is an important festival and just being included in it is significant. The categories Serbian – Croatian are not important to me in my personal life and especially not in my work. I consider myself a citizen of the world and view everything around me the same way. We all need to participate in creating a better society wherever we are and whoever we share the meridians and parallels with. Unfortunately, too often national and other identities are used to divide people instead of realizing that different customs and cultures are the beauty of a society and not its problem.

Too many rules force us to withdraw into ourselves

What connects all your movies – from Distortion from your college days to Memoirs of a Broken Mind shown at FEST and Erik – is the emphasis on the inner life of the protagonists, their psychological struggle and thought processes. How can we show others what is happening within us?

I follow certain postulates of my own, as honestly as I can towards myself and others, without any hidden intentions or ideas, with the opinion that humans are thinking beings often in a psychological conflict with the world they live in, which is full of limitations, boundaries and modes imposed by others. There should be rules, of course, but too many rules and limitations lead to a loop which makes us withdraw into ourselves. I love playing with this fine weave; I love when it comes to light, for it is the essence of all of us and of everything beautiful that a person possesses. Unfortunately, a person also possesses that which is not beautiful, but that is the beginning of solving the problems if an individual has them. All this comes naturally, as it were, without any artificiality.

You also place a lot of importance on local heroes, people we meet every day. How do you know that you “have a theme” for a movie?

Stories are everywhere around us, all kinds of them. And none is less important than the other. What story will be told depends only on the sensibility of the author. I like to say that I do not choose the theme, but rather the theme chooses me. It kind of materializes and will not leave me in peace until it is brought to light. I love dealing with people and society in my work. I believe we can live in a better society, and my themes follow this idea. There are a lot of steps to be made to untangle that knot, but one step at a time.

You usually direct, shoot and edit all by yourself. What are the advantages of that kind of work over work with a crew, or, in other words, how do you manage working all by yourself?

Both creative approaches are good. I prefer this way of working because I form a much more sincere relationship with my subjects. That is extremely important for the themes I deal with. It is great having a large crew and distributing the duties and loads, but this same crew can also be a hindrance because not everyone is at the shoot with the same goal. It all depends on what is being done and what the best way of doing it is for the final product to be great. This is my recipe, and it is ideal for me.

An important moment in your work is the movie An Art Folder Full of Dreams about the visual artist Predrag Spasojević. Since you did not have the opportunity to personally meet him, what was it like reconstructing his life?

Sadly, I did not have the opportunity to meet Predrag, and I learned about him through his work. I was astonished by the amount of work he had done and its enviable level of quality. A part of his work also marked my childhood, and it was very interesting to learn about him through the stories by his family, friends, acquaintances and colleagues. The producer of the film is Predrag’s partner, Biserka Vranić, who was a great and indispensable help in the organization and navigation through the sea of stories and characters. I am extremely pleased that the story of Predrag is here for all of us and those after us. He was a remarkable and very kind soul, who ennobled us with his work and reminded us of what is important in being human, something that is often neglected. I am pleased when I hear that people have the feeling they knew Predrag after watching the film. That was precisely the goal, for I also got to know Predrag through the film.

Documentaries are unjustifiably overshadowed by feature films

The famous question from childhood: who do you love more, but not mom or dad – editing or directing, feature films or documentaries?

Editing is my first love. I love its endlessness, its quirks, its process and its conflicts between the subjective and objective when something has to be given up. I love that it gives me the opportunity to play and create. Directing came later in my life, slowly got under my skin, and I have now put it on a pedestal as well, on par with my first love. They are, after all, complementary and cannot exist without each other. When it comes to feature and documentary films, I am not entirely decided. I love film in all its forms, but I prefer making documentaries due to their intimacy, sincerity and the fact the characters are here and now and are real, which is incredibly beautiful for me. I think that documentaries are unjustifiably fated to remain in the shadow of feature films.

Since you studied at academies in Belgrade and Ohio, can you compare the educational system in Serbia and the US?

It was great both in Belgrade and Ohio. Each academy had its advantages and drawbacks, but what is important is how much effort you make to get the best out of what is offered. I cannot say much about educational systems since it is not my area of expertise, but I can say that outdated systems need to change and innovations are necessary because times change rapidly and education should not become stuck in time.

Work with students at art academies differs from that at other universities, primarily in the work organized in small groups, in contrast with those where the student is just a number in the student document. What were the advantages of your type of education and what advice would you give to students not in that situation, the “nameless” ones?

What you study and eventually do in life is your own responsibility. The small groups at academies are an advantage in the educational sense; on the other hand, they are a clear indicator of what society thinks of artists – the fewer the better. No one has to be nameless or just a number in the student document or at the employment bureau. Besides, an academy or college does not define what and who we are; everyone should try to be the best they can and not let their fate be decided by others. You become nameless through your own choice.

How important for you was the role of the mentor, in your case the renowned editor Andrija Zafranović?

Andrija Zafranović is the person who showed me in the best way the struggle that awaits us and the sacrifices we must make to do what we love. I think all of us in his class were skeptics in the beginning – it was a consequence of the times – but the truth is that it is much harder today than it used to be. We live in a world where anyone who does not fit society’s mold is condemned to fail from the beginning. The only solution is to fight for your place under the sun with all you have, and that is not possible if you do not value and love what you do because that way you invalidate yourself and allow yourself to be defeated. Andrija indirectly taught us this. He did not let us be anything but the best we could be.

You have also worked on music videos, among them on the video for the cult Serbian band Goribor and their song “Dugo nisam bio tu”. Why do you like music videos and how do you choose which ones you will work on?

I did editing for the video for “Dugo nisam bio tu”, the rest was done by another, excellent team. Music videos are a form I like very much; in them you have to express yourself and create a whole new, little world in a few minutes. I do not do many music videos, but each is dear to me in a different way, and I choose them based on my own interests. It is important that I understand and recognize the lyrics and the music as something close to me. I do not necessarily have to listen to that type of music, but I have to have some connection to it and the performer. It is important to be on the same wavelength, as in most things.

Goribor’s front man, Aleksandar “ST” Stojković, withdrew from the Serbian musical scene a few years ago and moved to Pula, where you also live. Do you have any information about him that you could share with our readers?

Aleksandar is my acquaintance and recently also became my fellow citizen. I believe he is enjoying Pula, but for any other information about him and his current work, you will have to ask Aleksandar himself.

Music as an escape from the harsh reality

Music was also the theme of your movie The Dust of Everyday Life (2011), named after a quote by Pablo Picasso. What answer were you after in that movie, and do you think that the music scene is in a better position now, ten years later?

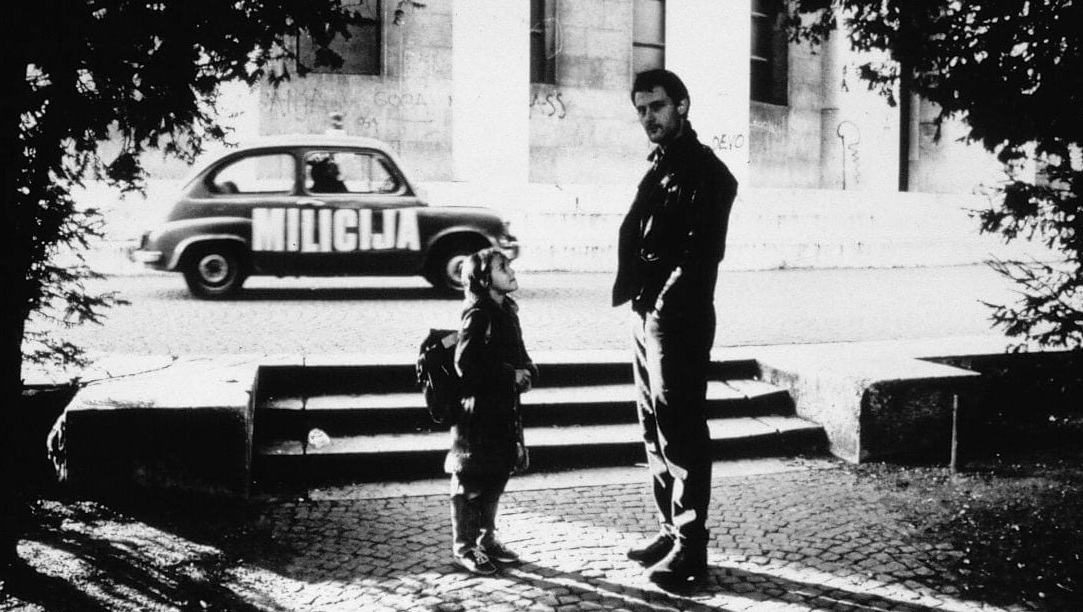

The movie The Dust of Everyday Life tried to give an overview of the music scene of Pula in the past and now. In my gymnasium days in the first half of the nineties, in those terrible times, there were a lot of bands in Pula; there was barely a basement, garage or attic without music being played. Music was at the time the only thing that lifted us out of our harsh reality. After high school, I did not live in Pula for many years, and it was interesting to see where music was at that moment, in peacetime. I did the movie with musician Marko Jovanović; the movie included and touched on many other socially relevant issues, for 2011 and today. Nothing much has changed. Independent music is disappearing, smothered by mainstream, just like film.

In Croatia and Serbia, the position of freelancers is a topic more relevant than ever due to the announced taxing and changes to the labor law, as well as the legal defining of digital nomads. Since you have been working as a freelancer for years, what is your position on this topic?

We must create. We certainly must fight for our rights because if we do not, they are gone. By this I do not only mean freelancers, but all people who work for a living. Circumstances are never ideal and are always far from what they could be. We have to find a way to change them for the better, to allow everyone in society, not just a privileged few, to feel better and have the chance to prosper.

Inspiration cannot be bought

Although you are from Serbia, you have lived in Croatia from a young age. How important is national identity to you, and how much are you affected by daily political events?

I believe that national identities make a society more wonderful and diverse. It bothers me when differences, whether national, racial, gender or any other, are perfidiously used to create divisions between people. Julius Caesar said “Divide et impera” (“Divide and rule”); nothing needs to be added there. It is wrong and useless. We should all strive to create a better society to the best of our abilities, for no one will do it for us. I do not concern myself with politics or follow it.

How did the pandemic affect your work, both regarding the film industry and inspiration?

I cannot talk about the domestic or foreign film industry because I do not have enough information about them. Independent art certainly suffers the most, but that is nothing new. The crisis in not new either; it is not alien or recent in our region but has lasted for a long time in various forms. In the previous system, you could not buy this or that; now you can buy it, but with what? Everything is more or less the same, only the rhetoric changes. I cannot even imagine what it would be like if I woke up tomorrow carefree; I do not know if I could manage. Whatever happens, it is important not to stop and not to give up; you have to regroup and keep going, stronger and smarter. When inspiration is there – it is there; when it is not – it is not. It cannot be bought and does not depend on financial power. I have no problem with it.

Translation from Croatian: Jelena Šimpraga